As the nights draw in, and Halloween approaches, there are some intriguing folklore tales – indeed some very reminiscent of traditional childhood fairy tales – from the Batley and Dewsbury areas. Some are well-known; others less so. Here are a selection.

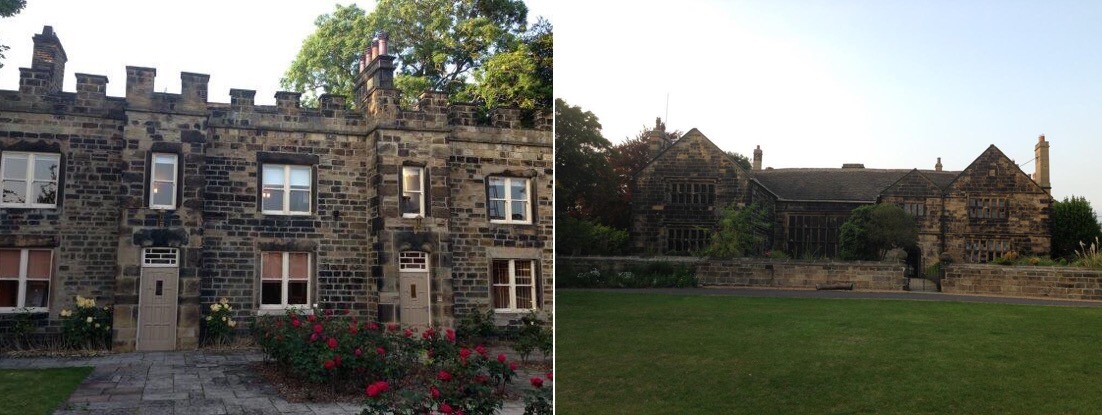

A well-known local legend is that of the ghost of Captain Batt at Oakwell Hall. No lesser person than Elizabeth Gaskell wrote about it in The Life of Charlotte Brontë.

She said of the Hall:

It stands in a rough-looking pasture-field, about a quarter of a mile from the high road. It is but that distance from the busy whirr of the steam-engines employed in the woollen mills of Birstall; and if you walk to it from Birstall Station about meal-time, you encounter strings of mill-hands, blue with woollen dye and cranching in hungry haste over the cinder-paths bordering the high road. Turning off from this to the right, you ascend through an old pasture-field, and enter a short by-road, called the “Bloody Lane” – a walk haunted by the ghost of a certain Captain Batt, the reprobate proprietor of an old hall close by, in the days of the Stuarts. From the “Bloody Lane,” overshadowed by trees, you come into the rough-looking field in which Oakwell Hall is situated. It is known in the neighbourhood to be the place described as “Field Head,” Shirley’s residence. The enclosure in front, half court, half garden; the panelled hall, with the gallery opening into the bed-chambers running round; the barbarous peach-coloured drawing-room; the bright look-out through the garden-door upon the grassy lawns and terraces behind, where the soft-hued pigeons still love to coo and strut in the sun, — are all described in “Shirley.”

Gaskell’s book goes on to describe the appearance of a bloody footprint in a bedchamber of Oakwell Hall. She reveals the story behind it, and its connection with the lane by which the Hall is approached.

Captain Batt was believed to be far away; his family was at Oakwell; when in the dusk, one winter evening, he came stalking along the lane, and through the hall, and up the stairs, into his own room, where he vanished. He had been killed in a duel in London that very same afternoon of December 9th, 1684.1

William Batt’s burial is recorded in the parish register of Birstall St Peter’s on 30 December 1684.2

A local roving non-conformist minister and gossipy diarist, the Rev. Oliver Heywood, gives more snippets of information about William Batt’s death. In his vellum book, which contained a register of various baptism, marriage and burial events, he noted in the burials section:

398 Mr Bat: in sport. 16843

Another publication of the Rev. Heywood’s varied documents has a further notation of the burial containing more details. No year is indicated but the entry is clearly referring to the death of William Batt:

Mr. Bat of Okewell a young man slain by Mr. Gream at Barne(t) near London buried at Burstall Dec. 304

Other sources indicate the duel was the result of a debt, possibly related to gambling.

And, although William Batt’s ghost has associations with ‘Bloody Lane,’ this footpath does not owe its name to him. ‘Bloody Lane,’ or Warrens Lane (now Warren Lane) to give it its proper name, earned its gruesome nickname as a result of the English Civil War Battle of Adwalton Moor of 30 June 1643. This was the likely route the defeated, fleeing Parliamentarian troops took to leave the battlefield.

Who knows whether the tale of William Batt’s spirit returning home is true? But it is as tale which has been passed down through the generations, and it is one still told today to Oakwell Hall visitors.

The 1662 publication Mirabilis Annus Secondus; or, the Second Year of Prodigies describes signs and apparitions seen in the Heavens (sky), Earth (land) and Waters in the months from April 1661 to June 1662. The section dealing with strange land-based sensations includes the following phenomenon from Batley from May 1662:

…at a Town called Batley in Yorkshire, about four miles from Wakefield, in the Ground of one Michael Dawson, about the Carr belonging to that Town, a man climbing up into an Oak-tree to cut boughs, perceived his clothes to be very much stained with Blood; and upon search, he found the under-side of the Oak-leaves to be all bloody, not only in that Tree, but in another also not far from it. Several of the Leaves of the said Trees were afterwards sent abroad to divers persons in the Country, who had a desire to see them, and the Blood was dried upon them, and they seemed as if they had been coloured and dyed therewith. This is a very certain truth, and attested by many eye-witnesses.5

The blood-like substance was possibly to be the result of a disease to the tree. But it caused a sensation back in 1662.

The next peculiar mythology centres around Batley Parish Church. It is described as follows:

On the eastern end of the outside of Batley Church, under the shade of the great eastern window, there is a not common tombstone; insomuch as on its centre there is a small brass plate, in size about eight inches by six, which once had upon it an inscription but can now only boast of a few unintelligible letters. The centre of this brass plate is worn hollow by a strange process. A tradition is current that any one who will put his hands upon this plate, and at the same time look up at the great coloured window – dedicated people say to the memory of a drunken woman – for five minutes he will not be able to take his hands off again. The appearance of the plate testifies to the popularity as well as the untruthfulness of this popular fit.6

Unfortunately these old tombstones were cleared from the churchyard, and it is therefore no longer possible to identify the one attracting the attention of adventurous 19th century Batley townsfolk. I wonder if anyone knows who it belonged to?

Mystical stories would not be complete without a haunted house. And, according to turn of the twentieth century accounts, one existed at Dewsbury. Located on Wakefield Road, some of the building dated to the time of Cromwell. It was part of the estate of a Manor House, the gardens and grounds of which stretched towards the Old Bank. It was an area thick with vegetation, with beauty spots in the Hollin[g]royd and Caulms Woods areas. A subterranean passage connected the two houses. Sections of this tunnel were in existence as late as the latter part of the nineteenth century.

According to legend, after the death of one particularly wicked (and unnamed) Lord of the Manor, he was unable to rest in peace. His midnight rambles terrified the local inhabitants, who were driven in fear to consult a local priest. This brave priest managed to communicate with the Lord’s troubled and troublesome spirit. The spirit agreed to retire and never return while Hollin[g]royd Wood grew green.7 I wonder if he is back now the wood is no more?

Purlwell Hall, which stood in the Mount Pleasant area of Batley, was also the subject of a romantic legend. The events, which are vaguely referred to as taking part in the mid-eighteenth century, centred around a young lady. Some versions say she was an orphan noted for her beauty, goodness and intellect, who lived with her aunt and uncle at the Hall.8 Others say she was the fairest and sweetest of three daughters of the household.9

Two men vied for her hand in marriage. One was honest but poor. The other a rich, handsome Captain. Unsurprisingly for those who follow fairy tales, the young lady fell in love with the poor suitor. But, as happens in these stories, her family rejected her choice. As a result they kept her locked away in the library – a small, square room in the hall. Here she was to stay until she changed her mind. But her love for the poor, honest man did not waver. He was ever in her thoughts as she gazed longingly out of the window, towards the hills to the south, clearly visible in the smokeless sky – this was obviously before Batley became famous as a mill town, full of chimneys belching out smoke!

The heart-broken girl whiled away the time in her prison etching a verse in the pane of one of the windows, with the diamond from a ring. Some say the ring belonged to her mother. Other more romantic accounts say it was from a ring given to her by her forbidden love. If so, he was not quite as poor as the tale makes out.

There are a number versions of this verse, one of which read:

Come, gentle Muse, wont to divert

Corroding cares from anxious heart;

Adjust me now to bear the smart

Of a relenting angry heart.

What though no being I have on earth,

Though near the place that gave me birth,

And kindred less regard to pay

Than thy acquaintance of to-day;

Know what the best of men declare,

That they on earth but strangers are,

No matter it a few years hence

How fortunate did to thee dispense,

If – in a palace though hast dwelt

Or – in a cell of penury felt –

Ruled as a Prince – served as a slave,

Six feet of earth is all thou’lt have.

Hence give my thoughts a nobler theme

Since all the world is but a dream

Of short endurance.10

Although there are no clues as to the period of time this lovesick damsel was incarcerated, given the length of the verse she etched it was clearly not a mere matter of days.

But, as in all good fairy tales, there was a happy ending. The captain tired of his hopeless pursuit of a fair lady who would never love him. Her parents (or adopted parents depending on the version), realising how much in love she was with the humble and honest suitor, relented; and Miss Taylor (as one version calls her) finally became the wife of her true love.

Is this based on true events? Who knows. However, what does seem beyond doubt, is the engraving on the window pane. This is as testified to by independent witnesses in the latter part of the 19th century when the Hall underwent renovations.

The next legend concerns Dewsbury Minster’s famous Christmas Eve Devil’s Knell. The tenor bell rings out in funereal manner once for every year since the birth of Christ to the present year, with the last toll falling on the stroke of midnight. The tolling is said to keep the parish safe from devilish pranks for the coming year.

There are various dates given for the commencement of this custom. Some say the 13th century, others the 14th or 16th. It appears, if these earlier dates were the case, the custom did lapse, for the ringing is recorded as definitely taking place from 1828.

One folk-lore journal, published in 1888, mentions this Christmas Eve bell-ringing at Dewsbury.11 It outlines the custom to toll the bells that night, stating this was an acknowledgment that the devil died when Jesus was born.

Elsewhere in the journal a curious tradition from Soothill is mentioned. It says that an unnamed master of an iron-foundry, in a fit of passion, threw a boy into one of his furnaces. The sentence passed on him was that he should build a yard all round an unspecified local church, and provide a bell for the steeple. The writer, who asks for more information about this incident, does not connect it, or bell, with Dewsbury Minster’s Devil’s Knell. Perhaps the omission is deliberate, in an attempt to tease out the truth. Because questions were being raised by some of the origins attributed to the Christmas Eve bell ringing.

These other stories linked with the origins of Dewsbury’s Devil’s Knell stated the tenor bell at Dewsbury Minster, Black Tom, was an expiatory gift from Sir Thomas de Soothill for the murder of a boy, whom he threw into the forge dam. Thomas de Soothill, who died in 1535, was a member of the Saville family and known locally as Black Tom, hence the name of the bell.12 There is therefore a clear similarity with the Soothill iron-foundry incident mentioned in the 1888 journal.

Yet another version states the tradition began in 1434. A local knight, or Lord of the Manor depending on this version, flew into a rage after hearing a servant boy had failed to attend Church and threw him into a pond, where he drowned. As his deathbed penance, the knight donated the bell to Dewsbury Minster Church of All Saints, requesting it be tolled every Christmas Eve.13

An 1880 edition of the Dewsbury Reporter cast doubt on the Black Tom origins story.14 Essentially, they say there were no mention of any bells currently in the church, which were recast in 1875, existing in the Minster prior to 1725. They also asked for evidence of this murder incident, along with the timeline for Thomas de Soothill’s life, and the location of the supposed forge.

Whatever its beginnings, the Christmas Eve Devil’s Knell is tolled to this day. Here’s a link to a video by the bell-ringers at the Minster tolling the Christmas Eve Devil’s Knell, with their version of its origins

The final fantastical tale also involves a branch of the Savile family. This time the ones whose residences included Howley Hall. It is supposedly (though not conclusively) centred around Anne Villiers, daughter of the Earl of Anglesey, or Anne Sussex as she was subsequently known. She became the second wife of Sir Thomas Savile (1590-1659), whose titles, at this stage, included Viscount of Castlebar and Baron Savile of Pomfret. Anne and Thomas married at St Mary’s, Sunbury on Thames on 20 January 1641[2].15 He was made the 1st Earl of Sussex (in the third creation of this title) on 25 May 1644.

Lady Anne’s Well, which is reputedly named after the aforementioned Countess of Sussex, lay on the south-east side of Howley ruins, near to Soothill Wood where several springs flowed to furnish the well.

Lady Anne, so rumour has it, liked to bathe in the waters of the well. The legend is that one day, whilst in the process of immersing herself in these cleansing waters, she was caught and devoured by a wild animal or animals – some go as far as to say it was a lion.16

The spot where her mangled remains were discovered became holy ground. The pure waters of the well were subsequently said to possess supernatural properties, and changed colours, with this miracle occurring annually at 6 o’clock on Palm Sunday morning. Hundreds of people converged on this site at the specified day and hour, brandishing twigs and switches to represent palms. By the mid-19th century the well bore an obliterated inscription, and had an iron basin, or ladle, attached to the stonework with a chain.

Even Elizabeth Gaskell in The Life of Charlotte Brontë covered the legend, but in her version it was another type of wild creature responsible for the killing. In her book, published in 1857, writing about Howley Hall, which now belonged to Lord Cardigan, she said:

Near to it is Lady Anne’s well; “Lady Anne,” according to tradition, having been worried and eaten by wolves as she sat at the well, to which the indigo-dyed factory people from Birstall and Batley woollen mills yet repair on Palm Sunday, when the waters possess remarkable medicinal efficacy; and it is still believed that they assume a strange variety of colours at six o’clock in the morning on that day.17

The supposed incident was even the subject of verses in later years, including:

‘Twas such a place, sequestered glade,

Where Lady Anne was lifeless laid;

While bathing there, as people say,

A lion seized her for his prey:

Her cor[p]se was made the wild beast’s food,

He ate her flesh, and drank her blood;

And now the spot is holy ground,

Where Lady Anne’s remains were found,

Hard by a well which bears her name,

A lasting tribute to her fame;

There youths and maidens often go

Their sympathetic love to show,

And mourn her fate, unhappy maid,

Who perished in the Sylvan shade.

Palm Sunday is the annual day

When lads and lasses wend their way

To this sad spot, there gather palms,

As employs of the fair one’s charms;

Homeward again they do return,

And water take in can or urn,

Which they suppose contains a charm

That will preserve them from all harm.18

In the late 1880s the area around the well was destroyed when the wood was bisected by the Great Northern Railway Line covering Dewsbury, Batley and onto Leeds via Beeston. This Beeston and Batley branch of the line opened in August 1890, and included a 732-yard long tunnel located near to the well, though the spring still existed for the use of residents living in nearby cottages. Yet the legend lived on.

If true, you would expect this extraordinary event to be widely publicised, especially given it involved a member of the aristocracy. It is not. And, as with many other of these tales, it is decidedly vague with facts.

More than that, there are other fatal flaws to this lion-eating (or should that be a pack of wolves) tale. Not least is the one concerning the reputed victim of these voracious beasts. According to Cockayne’s Complete Peerage, Anne Villiers outlived her husband, Sir Thomas Savile. He died in circa 1659 (his will was proved on 8 October 1659). By the time Anne died in around 1670, she was the wife of Richard Pelson. Their daughter, Anne, went on to become the wife of James Tuchet, 5th Earl of Castlehaven. Furthermore, according to Cockayne, the former Anne Villiers died at St Giles’ in the Fields, London – some 200 miles away from any wild animals at the well.19 He certainly makes no reference to her being killed in a tragic accident involving wild animals.

There is also the issue around the type of creature responsible for the supposed mauling. Although there were reports of wolves living wild in Scotland up until the 18th century, it is generally accepted that wolves were extinct in England by the 15th century. As for wild lions, well the wealthy were known to keep them as part of menageries, including at nearby Nostell Priory. But as for an escaped killer lion prowling Soothill Woods in the 17th century, that seems the stuff of fantasy.

However, suppose it is not the 1st Earl of Sussex’s wife being referred to? The reports I’ve read either refer to Lady Anne or Lady Anne Sussex. Could it possibly therefore be the subsequent Countess of Sussex? James Savile, the son of Thomas Savile by Anne Villiers (the 1st Countess Sussex), who succeeded his father to the earldom, married Anne Wake. According to Cockayne’s Complete Peerage, after his death in 1671, when the earldom became extinct, she went on to marry Fairfax Overton. Looking at Marriage Bonds and Allegations, this marriage took place in around April 1674.20 According to Cockayne she died in 1680 – and again there is no mention of a dramatic death associated with her. There is also the same issue with the existence of wild animals.

There are other theories too about the well’s miraculous powers. These include rumours that the waters of the well had reputed holy properties even before this supposed incident, with inhabitants of the area visiting it from possibly as far back as pre-Norman times. Some sources point out that it was quite common for wells of pure water in solitary locations throughout the country in the early years of Christianity to be attributed with these holy and healing properties. As a result they became places of pilgrimage, visited and decorated on Holy Days like Ascension Day or, in this instance, Palm Sunday.

Due to the holy nature of the area, it is theorised that in the immediate neighbourhood a small chapel (Fieldkirk) existed in pre-Norman times, before the church in Batley was erected. There is even speculation about an annual Fair, Fieldkirk Fair, taking place either in the churchyard of this small chapel, or adjoining it. Norrison Scatcherd in his 1870s history of Morley mentions villagers returning from the annual Palm Sunday assemblage as saying they had been to Fieldcock Fair – which he quite reasonably suggests is a corruption of this old Fieldkirk Fair.21

This early Christian link, then, may have been the origins of the miraculous colour-changing well, not any killer animals devouring a bathing countess – the latter probably being invented to add spice to attract the Victorian generation. Nevertheless it is an interesting local legend.

As I said in the introduction, this is only a selection of folklore tales and mysterious happenings associated with the area. Many have a common thread: unspecified, or uncertain, dates; discrepancies about the names of central characters, most of whom are local gentry or aristocracy; there is even confused information, for example lions or wolves, orphan or daughter, iron foundry master or knight, ponds or forge furnaces.

But all these tales are part of the area’s history and would have been familiar to our ancestors living here, which is why they are worth preserving.

If you have any similar strange local anecdotes and legends associated with the Batley and Dewsbury areas do let me know.

With thanks to fellow AGRA Associate Joe Saunders who tipped me off about the mystery of the bloody oak leaves tale.

Postscript:

Finally a big thank you for the donations already received to keep this website going.

The website has always been free to use, but it does cost me money to operate. In the current difficult economic climate I am considering if I can continue to afford to keep running it as a free resource, especially as I have to balance the research time against work commitments.

If you have enjoyed reading the various pieces, and would like to make a donation towards keeping the website up and running in its current open access format, it would be very much appreciated.

Please click here to be taken to the PayPal donation link. By making a donation you will be helping to keep the website online and freely available for all.

Thank you.

Footnotes:

1. Gaskell, Elizabeth Cleghorn. The Life of CHARLOTTE Bronte, Author Of “Jane Eyre”, “Shirley”, “Villette”, Etc. Smith, Elder & Co, 1857;

2. Birstall St Peter’s parish Register, West Yorkshire Archive Service, Reference: WDP5/1/1/1;

3. Heywood, Oliver, and J. Horsfall Turner. The Rev. Oliver Heywood, B.A., 1630-1702, His AUTOBIOGRAPHY, Diaries, Anecdote and Event Books: Illustrating the General and Family History of Yorkshire and Lancashire. 2. Vol. 2. Brighouse England: A.B. Bayes, 1882;

4. Heywood, Oliver, Thomas Dickenson, and J. Horsfall Turner. The Nonconformist REGISTER, Of Baptisms, Marriages, and Deaths: 1644-1702, 1702-1752, Generally Known as the Northowram Or Coley Register, but Comprehending Numerous Notices of Puritans And Anti-Puritans in Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cheshire, London, &c., with Lists OF Popish RECUSANTS, QUAKERS, & C. Brighouse: J.S. Jowett, printer ‘News Office’, 1881;

5. Mirabilis Annus SECUNDUS, Or, the Second Year of Prodigies: Being a True and Impartial Collection of Many Strange Signes AND Apparitions, Which Have This Last Year Been Seen in the Heavens, and in the Earth, and in the Waters: Together with Many Remarkable Accidents and Judgements BEFALLING Divers Persons, According to the Most Exact Information That Could Be Procured from the Best Hands, and Now Published as a Warning to All MEN Speedily to Repent, and to Prepare to Meet the Lord, Who Gives Us These Signs of His Coming, 1662;

6.Yorkshire Folk-Lore Journal: With Notes Comical and Dialetic .. Bingley: Printed for the editor by T. Harrison, 1888;

7. Batley News, 24 May 1902;

8. Yorkshire Folk-Lore Journal: With Notes Comical and Dialetic .. Bingley: Printed for the editor by T. Harrison, 1888;

9. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 29 March 1901;

10. Ibid;

11. Yorkshire Folk-Lore Journal: With Notes Comical and Dialetic .. Bingley: Printed for the editor by T. Harrison, 1888;

12. Greenwood’s History, as quoted in the Dewsbury Reporter, 31 January 1880;

13. Yorkshire Post, 23 December 2015;

14. Dewsbury Reporter, 31 January 1880;

15. Parish Register, St Mary’s, Sunbury on Thames, London Metropolitan Archives, Ref: DRO/007/A/01/001;

16. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 3 July 1880;

17. Gaskell, Elizabeth Cleghorn. The Life of CHARLOTTE Bronte, Author Of “Jane Eyre”, “Shirley”, “Villette”, Etc. Smith, Elder & Co, 1857;

18. Dewsbury Chronicle and West Riding Advertiser, 9 July 1887

19. Cokayne, George E., ed. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: EXTANT, Extinct or Dormant. By G.E.C. 7. Vol. 7. London: George Bell & Sons, 1896;

20. Fairfax Overton and Ann Conntesse Marriage Allegation, Parish – St Giles in the Field, London Metropolitan Archives, Ref: Ms 10091/28

21. Scatcherd, Norrison Cavendish. The History OF MORLEY, in the West Riding Of Yorkshire: Including a Particular Account of Its Old Chapel. Morley: S. Stead, 1874.

Other Sources:

• Baker, Margaret. Discovering Christmas Customs and Folklore: A Guide to Seasonal Rites. Princes Risborough, Bucks, UK: Shire Publications, 1992;

• The Batley News and Birstall Guardian, 22 August 1885;

• Batley Reporter and Guardian, 2 August 1890;

• Dewsbury Chronicle and West Riding Advertiser, 10 July 1886;

• Green, Martin, and Martin Green. Curious Customs And Festivals: A Guide to Local Customs and Festivals throughout England and Wales. Newbury: Countryside Books, 2001;

• The History of Wolves in the UK, https://wolves.live/the-history-of-wolves-in-the-uk/;