On an evening in late May 1942, under cover of darkness in wartime black-out Batley, a bizarre crime was under way. The mystery would make headlines in newspapers across the country – including the nationals.

On Saturday night, 23 May, Allan Pollard of Coal Pit Lane, employed by Batley Corporation as the Cemetery Ranger, undertook his normal routine at Batley cemetery. At 8pm, after checking thoroughly to make sure everything was in order and that the grounds were empty of the living, he locked the gates for the night.

In Batley police station, Monday 25 May was proving a fairly routine morning for 27-year-old Police Constable Arthur Peakman of the West Riding of Yorkshire Constabulary. But things took a dramatic turn and became anything but routine at 9.25am, when Robert Edward Cardwell, foreman gardener at Batley cemetery, burst in to report a strange occurrence.

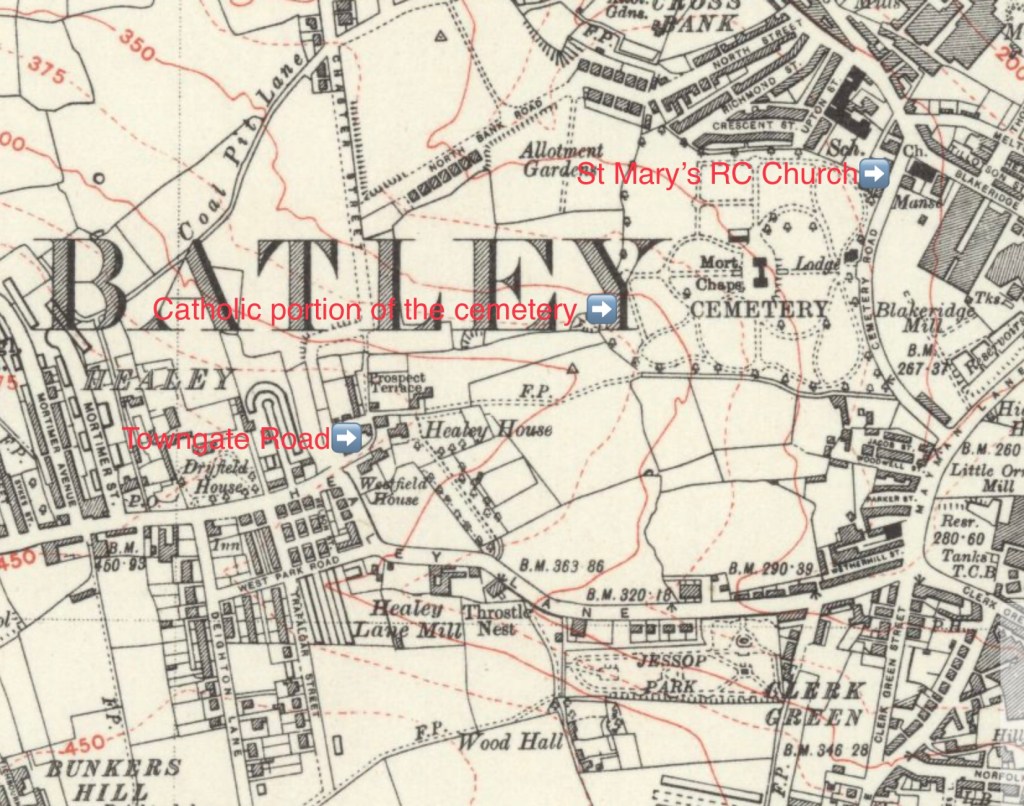

Cardwell lived on Towngate Road, local to the cemetery, and had entered the cemetery grounds at 7.50am on Sunday morning. He could not believe the sight which met his eyes in the Roman Catholic portion. One of the graves, S.1078, had been re-opened. The opening measured five feet long, two feet wide and five feet deep. Soil had been thrown on surrounding graves causing damage to five of them, estimated to be around five shillings in each case.

Cardwell initially informed Fred Burn, the Cemetery Registrar, who confirmed the grave had been opened without his permission. After going through the register and identifying the owners of the affected graves, they agreed the incident must be reported to the police… although there was a delay of a day between the discovery of the incident and its official reporting.

After hearing Cardwell’s incredible tale and taking down his official statement, PC Peakman, accompanied by his superior, Sergeant Micklethwaite went to investigate. The graves were located near to the boundary wall on the Healey side of the cemetery. In this period, prior to the building of Healey Estate, it was a particularly secluded area.

With trepidation, the two policemen used a prodder to examine the plot further. It was with immense relief that around one foot below the re-opened depth the prodder struck something solid – the coffin was still there. It had not been tampered with. Nothing appeared to have been stolen from this grave, or those surrounding it.

Continuing their search of the cemetery and surrounding fields, the policemen found traces of clay on the boundary wall, indicating where someone had climbed over to the Cemetery Fields footpath. There the trail ended. The police also found a small area of clay with the imprint of clothing on it. The assumption is this is where the culprit had knelt. Unfortunately the ‘digger’ had been sufficiently alert to ensure he left no tools.

The conclusion of the investigating officers was :

The person who re-opened the grave is evidently strong and virile and might be called an expert in the use of a spade judging form the method in which he cut the clay out.1

But who had carried out this act? And why, as none of the burials in the graves involved in this odd event were so remarkable as to warrant this attention? Was it a solo venture, or were there accomplices? What was being sought? Did the ‘digger’ or ‘diggers’ achieve their objectives, or were they disturbed? Did they fail to complete their task before daybreak and the lifting of blackout restrictions, just after 5am. And which graves were involved?

The disturbed plot was owned by Lilian Igo. The grave contained the body of her husband, 32-year-old James Igo, a Denby Grange Colliery miner, who died in hospital on 8 February after a sudden illness. A parishioner of St Joseph’s, the Batley Carr Catholic parish, his funeral was conducted in Batley cemetery on 13 February 1940.

The damaged graves belonged to:

- Michael Finn, an ex-serviceman from the Great War. His wife Ann was buried there on 24 April 1941, age 60.2 They were St Mary’s parishioners.

- James Harkin (sometimes the spelling is Horkin). The Harkin family were associated with St Mary’s parish. James’ 57-year-old wife, Mary, was buried there on 2 April 1931.

- John William Harkin, whose 45-year-old wife Mary Jane, was buried there on 30 March 1941.3 This family were also associated with St Mary’s.

- Mary Hill. This grave contained the body of her 33-year-old husband John Herbert (Jack) Hill. He had been killed in a tragic accident whilst building an air-raid shelter at Batley Hospital on 14 March 1940. A former St Mary’s parishioner, the family had recently moved into St Joseph’s parish.

- Mary Travis. The most recent burial in this grave, on 17 October 1940, was 44-year-old Harold Travis, husband of Agnes (formerly Cairns) of St Mary’s parish.

Following up, PC Peakman now conducted a series of interviews. Later that day he took formal evidence from Cemetery Ranger Allan Pollard, who was adamant that between 6pm and 8pm on 23 May, on his two visits in the vicinity of the grave, all was correct.

Peakman also spoke with Mary Ann Igo (mother of James), Lilian Igo (his widow) and Fathers Kennedy and McMendmin, priests at St Josephs, who had officiated at the funeral.

Accompanied by Inspector Hunter, Peakman’s enquiries continued. These included another visit to Lilian Igo. The policemen also spoke with her father, Harry Riley. Others questioned included Joe Igo and his wife, (brother and sister-in-law of James), Edward Kerfoot (stepbrother of James) and Fathers McBride and Mahoney of St Mary’s. All to no avail. No useful information was gained. They were no further forward in solving the mystery.

The police maintained a nightly vigil of the cemetery for a week afterwards, but no further incidents occurred.

The Batley News paid surprisingly little attention to the strange goings-on in the cemetery, giving them minimal coverage. Describing it as an “Incident That Stirred up the Imagination”4 the newspaper castigated London and provincial newspapers for letting their imaginations run riot. The Batley News take was:

…there is little to relate except that the earth was removed in the dead of night and the digging had been neatly done…it seems a trivial event in the history of a town to create national interest.5

But national interest it did create, with reports of police guards in the cemetery to prevent further desecration of graves. The Daily Mirror even interviewed James’s bewildered mother, with her quotes appearing in the newspaper, as follows:

Why should James’s grave have been chosen? He had not been married for a year when he died in hospital a few days after two urgent operations.6

The most macabre theory doing the rounds involved a Yorkshire murder victim.

On the evening of 10 June 1939 Charles Borman, an amateur bird-spotter, made a gruesome discovery in a hedge at Leggett Wood, Scholes: a newspaper parcel containing the head of a woman. Police were summoned and two further similar parcels discovered, containing the woman’s left arm and left leg. The woman’s torso was discovered two days later in Low Wood, near Wellington Hill, Leeds.

The victim was identified as 20-year-old Thornhill-born Ethel Wraithmell, also known as Shirley, whose last known residence was Leeds.

Ethel’s brother, Harry, lived in Batley. For this reason apparently, on 21 July 1939, her remains were encased in a square box and interred in a public grave in Batley cemetery. The location of this public grave was only yards away from the disturbed graves.

Police continued to investigate the “Leeds Torso” case. Almost a year elapsed before it was finally solved. On 27 April 1940, 28-year-old railway worker Wilfred Lowe handed himself into the police, with the words:

I have heard you have been making further inquiries and I have come to tell you it is me you want.7

Wilfred Lowe’s trial commenced at Leeds Assizes on 15 July 1940. He pleaded not guilty. On the second day of the trial, the jury reached its verdict. They agreed, acquitting him of murder, but finding him guilty of manslaughter. He was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment.

These sensational events would still be very familiar to many West Riding folk. However, in Batley, the theory of any link between the Wraithmell case and the grave re-opening was roundly dismissed. Registrar Fred Burn told the police he believed the perpetrator had opened the grave he intended to, as all the graves in that portion had number stones. It was not a case of mistaking the grave for that of Ethel Wraithmell.

With police investigations at a dead end, on 3 June 1942 Dewsbury-based Superintendent Stone, wrote to the Batley Town Clerk to inform him that:

…so far no trace has been found of the person or persons responsible….Should any information concerning the matter be obtained I will have you informed.8

The files I viewed contained no further information, although it is clear some other documents concerning the case did exist. Unfortunately, I have not traced them. Perhaps they do not survive.

However, this story does show the importance of local archives. I found the initial information about this bizarre episode purely by chance. I was intrigued by a West Yorkshire Archive Service (WYAS) catalogue description which read “Crime report relating to the re-opening of a grave by persons unknown in Batley Cemetery.” The documents were held by the Kirklees Branch of the WYAS. I quickly made an appointment to view them before this branch’s temporary closure.

When I began reading the file, my interest increased, because it was the Catholic part of Batley Cemetery. It fitted in with my Batley St Mary’s one-place study. My jaw hit the floor though as I read on. One of the graves involved in the incident was my grandad’s.

The files held a series of crime scene photos – and these include my grandad’s damaged grave, with its original wooden cross maker. I cannot publish these photos as they are subject to WYAS copyright. But they are an amazing addition to my family history. And it was a story no living member of the family had heard about.

It goes to show that archives catalogue descriptions (if they do exist, as not everything is catalogued) do not always tell the full story – they are signposts. And research curiosity does sometimes really pay unexpected dividends.

As yet I’ve not found out the identity of the individual(s) who tampered with the grave. Neither have I found a motive. Perhaps the mystery was never solved….unless you know different?

Postscript:

Finally a big thank you for the donations already received to keep this website going.

The website has always been free to use, but it does cost me money to operate. In the current difficult economic climate I am considering if I can continue to afford to keep running it as a free resource, especially as I have to balance the research time against work commitments.

If you have enjoyed reading the various pieces, and would like to make a donation towards keeping the website up and running in its current open access format, it would be very much appreciated.

Please click here to be taken to the PayPal donation link. By making a donation you will be helping to keep the website online and freely available for all.

Thank you.

Footnotes:

1. Crime report relating to the re-opening of a grave by persons unknown at Batley Cemetery, WYAS, Ref KMT1/Box63/TB83.

2. In Robert Edward Cardwell’s witness statement, as taken by PC Peakman, Michael Finn is incorrectly referred to as Michael Timms.

3. The Batley Cemetery Burial Register incorrectly records her age as 69.

4. Batley News, 6 June 1942.

5. Ibid.

6. Daily Mirror, 1 June 1942.

7. Yorkshire Evening Post, 21 May 1940.

8. Crime report, Ibid.

Other Sources:

• 1939 Register.

• Batley Cemetery Burial Register.

• Batley News, 22 July 1939, 17 February 1940, 16 March 1940, 23 March 1940, 20 July 1940, 19 October 1940, 5 April 1941, 26 April 1941, 23 May 1942.

• Bradford Observer, 30 May 1942.

• Census of England and Wales, 1891 – 1921.

• Daily News (London), 30 May 1942.

• GRO Indexes.

• Leeds Mercury, 15 June 1939, 22 June 1939, 23 June 1939.

• Nottingham Evening Post, 30 May 1942.

• Parish Registers (various).

• Yorkshire Evening Post, 12 June 1939, 13 June 1939, 14 June 1939, 15 June 1939, 17 June 1939, 22 June 1939, 29 April 1940, 21 May 1940, 3 July 1940, 15 July 1940, 16 July 1940, 17 July 1940, 29 May 1942.

• Yorkshire Post & Leeds Intelligencer, 12 June 1939, 13 June 1939.