12 December 1940 had been a cold winter’s day. As darkness drew in, families across the Heavy Woollen District prepared to hunker down for their second wartime Christmas.

Money was tight – no change there for most. So no sacks full of Christmas presents for the children. Again no change for many. But people were making the best of it, continuing peacetime Christmas traditions. Like the Hartley family in Savile Town, making a Christmas cake with a neighbour that evening – a reminder of the ordinariness of preparations of past Christmases [1].

But this was far from a normal Christmas. The strangeness of separation from loved ones in this so-called season of goodwill, bundled up with anxiety for the safety of those absentees, bound lots of families together. Mrs Hill in Batley faced a difficult Christmas – her first as a young widow with four children under the age of six. Over in Dewsbury, the Callaghan family were getting ready to spend Christmas with their latest family addition, a seventh child born earlier that year. Their eldest, 15-year-old Jack, typical of many teenage lads, was caught up with the excitement of pretending to shoot German planes out of the Yorkshire skies from his open bedroom window, accompanied by his own ack-ack-ack sound effects. His Air Raid Protection (ARP) Warden father quickly dragged him away, ensuring the window was firmly shut and blacked out. Within four years Jack would be serving with the Royal Navy craft in the D-Day landings.

At around 7.30pm the blood-chilling wail of the air raid sirens sounded across the Batley and Dewsbury districts, ending that evening’s attempts to recreate the normal of Christmases past. This was their new wartime normal. The anti-aircraft guns, based in Caulms Wood and what is now hole number 2 of Hanging Heaton Golf Club, began firing.

Perhaps there was an air of calm as people made their way to various air raid shelters. After all, they’d experienced this before, and the alarms always proved thankfully false.

Various organisations had these bomb shelters – for example St Mary’s RC school’s log book notes shortly after the war declaration that air raid shelters were built. One was under construction at Batley hospital in March 1940 – I know because it cost my grandad his life. Some sheltered in the strongest part of their house – cellars, sculleries, or simply under kitchen tables.

Others had purpose-built Anderson shelters in their gardens, erected right from the early days of the war. My dad remembers his dad building one, which would’ve been in the very first months after war broke out. Many families kept theirs post-war, converted to garden storage. They were a common site for many a year after the war.

Communal shelters existed with wooden slatted seats inside, like the soil-covered brick built one at Staincliffe. There was also a communal shelter at Leeds Road, Dewsbury. The tunnel at the bottom of Primrose Hill, close to Lady Ann Road, was another example. Vera May recalls sheltering there as a child during the 12 December 1940 raid. Men who worked at Taylor’s mill were also there, and Vera remembers: ‘They were great with us children, singing with us so we would not be afraid’ [2]. For, unlike most nights, this was no false alarm. The Luftwaffe this time were not passing over Batley and Dewsbury on their way to/from bombing another unfortunate town or city. Tonight it was for real, the turn of the heart of the Heavy Woollen district with its rail lines and mills manufacturing cloth for the military to face Hitler’s wrath.

Following the failure of the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe were now targeting Britain’s industrial and military centres. Sheffield was the focus for Operation Crucible, with bombing during the nights of the 12 and 15 December 1940. The targets of the raids were the multiple steel and iron works, collieries, and coke ovens along the Don Valley. One theory is that the bombing of Batley and Dewsbury was a mis-targeting from this attack, rather than these two towns being the specific objectives. Whatever, the results were disastrous for many of the townsfolk.

The night sky over Batley and Dewsbury lit up with parachute flares and tracer fire, as baskets of incendiary bombs and parachute mines rained down. Houses shook, window frames rattled, glass shattered, masonry and roof slates tumbled to the ground, water spurted out from fractured taps and pipes, and plaster fell from ceilings. As the bombs hurtled earthwards they made terrifying whistling and screaming sounds. Those sheltering braced themselves for the next ‘hit’, hunched over with hands protecting heads, then after each blast ensuring all others in the shelter were still OK.

It was not a constant bombardment. In the quieter periods, when the drone of the planes died away, people emerged troglodyte-like from their places of safety to check the damage, try extinguish any lights, and bale water onto house fires. Then they darted back in at the launch of the next attack wave.

Geoffrey Whitehead, an eight-year-old Batley schoolboy, vividly recalls that terrifying night. His grandparents, Charles and Harriet Whitehead, ran the off-licence at 1 Bunkers Lane. They also lived ‘over the shop’, along with Geoffrey and his parents. When the sirens sounded, Geoffrey’s father, Austin, set off towards Mayman Lane for his voluntary Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) work. Normally the rest of the family would go to the brick-built communal shelter at the bottom of Common Road. But the planes were upon them too quickly. With bombs already raining down, there was simply not time to risk walking the short distance to Common Road. Instead the family made their way down to the beer cellar and sheltered under the table there. The cellar roof was reinforced with plaster-covered wooden planks. So great were the shock-waves from the bombs, in particular one huge blast, that white plaster flecks came away from the ceiling [3].

As time passed, the air became ever more thick with smoke and dust, flames engulfed buildings, while the stench of sulphur from the high explosive bombs weighed heavy. Throughout it all, the Civil Defence Services, stretched to the limit, worked valiantly. They were assisted by brave and alert householders who had buckets of sand and water at the ready. These AFS personnel (Austin Whitehead possibly amongst them), soldiers, police and ARP Wardens checked on sheltering householders, went into homes to extinguish fires left in grates, smothered incendiary bombs with sand, operated stirrup pumps to douse flames, entered burning buildings to ensure no-one was inside, retrieved valuables and carried furniture from homes impossible to save. Delayed action fuse bombs and unexploded devices posed further threats to the rescuers. Yet they carried on regardless in the face of unimaginable danger.

Numerous incidents were reported across Batley. Joe Shepley, a fruiterer and ARP Warden, and David Woodcock were injured by flying splinters. One housewife caught an incendiary bomb in a bucket of water as it ripped through her ceiling – fortunately little damage was done. The home of Albert Stevenson and his bride of three weeks, Edith (née Thewlis), had a similarly lucky escape when soldiers quickly extinguished an incendiary bomb which landed in their bedroom. Private Rutter risked his life by entering a blazing building in which he thought someone was trapped. Luckily no-one was inside, but the soldier had the presence of mind to bring out furniture. Soldiers saved a laundry from flames, as well as the Well Lane mineral water works, despite knowing there was an unexploded bomb near the latter.

In the same area of Well Lane, Superintendent Horace Horne, an ambulance driver, had been instructing a class of ambulance cadets when the first bombs fell. They assisted in the operations to save the St John Ambulance headquarters and a storage building opposite, removing to safety the ambulances and most of the first aid stores.

Others reported the AFS and ARP personnel ‘carrying an adult invalid from a dilapidated house’ and ‘searching beneath a mass of overhanging slates and splintered rafters for someone who might be trapped in debris’ [4].

A cinema was hit, but again escaped relatively unscathed. Bombs landed in fields – I wonder if this was the one which my dad remembers landing in Carter’s field? My uncle can also remember a massive depression at the bottom of Healey Lane which he believed was a result of bomb damage. Was it from this raid?

And the major blast which shook the cellar in which Geoffrey Whitehead sheltered, was the result of a huge bomb which landed in fields near what is now Manor Way. He visited the crater site the following day and recalls the hole being so huge you could fit a double decker bus in it. He also remembers collecting shrapnel from it, now long since lost [5].

The Purlwell area of Batley was particularly badly affected. St Andrew’s church was the first in the Wakefield Diocese to be damaged by air raids. In the immediate aftermath repair costs were put at £1,000. The £400 East Window was pitted with splinters. One wall was so unsafe, with the organ visible through a gaping crack in the masonry, that rebuilding was thought necessary. The only door not blown out was the stout, oak entrance door.

Houses round and about the church suffered significant bomb and blast damage. It was in this locality that Batley’s first air-raid fatality lost his life. Private Herbert Courtney Channon of the Royal Army Service Corps was in Purlwell Hall Road when he was struck in the neck by shrapnel and killed instantly. Some say he was decapitated. His friends, standing either side of him, had lucky escapes being flung to the ground by the blast. Private Channon’s body was returned to his family for burial in Chard, Somerset later that month [6].

Even with the departure of the German raiders in the early hours of the 13 December, the danger did not pass. As the all-clear rang out at around 1am, amidst air thick with smoke and fumes, the rubble of smouldering buildings, the danger of unstable masonry and the risk posed by unexploded and delayed action bombs, the civil defence volunteers and demolition squads continued to work. The presence of ‘live’ devices meant the temporary evacuation of many houses, swelling the ranks of those bombed out of their homes.

Around 400 Batley residents slept that night in a school refuge centre. They were given meals in two Sunday schools. Most of the displaced were thankfully able to return to their homes by the following nightfall. One Batley man whose house suffered bomb appreciatively stated:

Kindly folk spontaneously brought food for us, invited us to their houses for meals. Tradesman offered us anything we needed, and young ladies served hot tea to us during the salvage. [7]

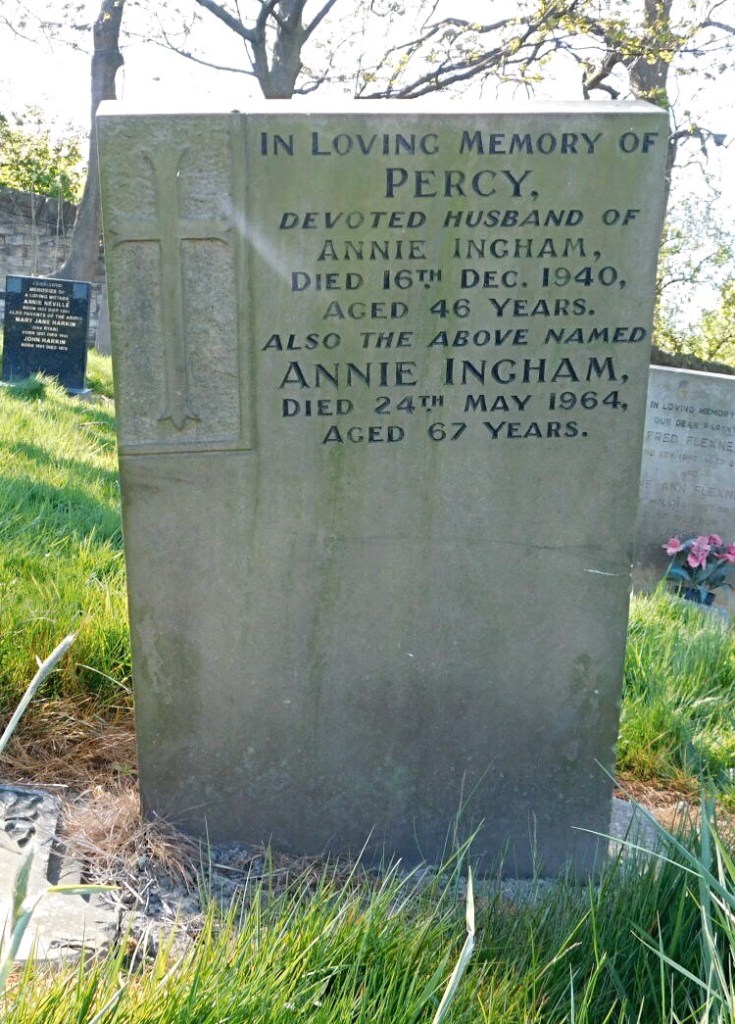

According to the official statistics compiled from Intelligence Reports into enemy activity on British domestic soil, that night Batley suffered five casualties comprising one killed and four injured. In fact two people in the town died as a result of the German raid. In addition to soldier Herbert Courtney Channon, local mill hand Percy Ingham also lost his life.

Percy was born in Birstall on 24 April 1894, the son of Harry and Sarah Ann Ingham. He married Annie Phillips on 7 February 1920 at St Mary of the Angels RC Church in Batley.

On the night of the raid, Percy sustained injuries at his home at 61 Purlwell Hall Road, the same street where Private Channon was cut down. Percy was taken to Staincliffe hospital where, despite all efforts, he died on 16 December 1940. Part of the old hospital buildings (previously Dewsbury Union Workhouse and the workhouse infirmary, as well as a military hospital in the First World War) exist today.

Percy’s funeral, conducted by Catholic priest John J Burns, took place on 20 December 1940. He is interred in Batley cemetery and his resting place is marked with a headstone. He is also commemorated in the roll of Wold War Two civilian dead held at Westminster Abbey, and on the Commonwealth War Grave’s Commission (CWGC) database.

Neighbouring Dewsbury also suffered in the 12 December raid, with five people losing their lives.

Brenda Hartley, her mother Hilda and neighbour Nellie Naylor, abandoned their Christmas cake baking at 13 North View, Savile Town. Initially they went into their cellar, but as Nellie’s husband, Harry, was due home they made a hair-raising dash to the cellar in the Naylor house next door but one. It was a decision which saved their lives. Harry arrived 15 minutes later. Shortly afterwards a bomb landed on the house they had vacated only a short time ago.

Initially unconscious, the group soon came round to find they were now buried alive. Their terrifying ordeal lasted several hours. Brenda’s mother sustained severe injuries, unable to move under the debris. There was a fear at one point that Hilda would drown, when water used to put out the fires above seeped steadily into the cellar. Harry, thankfully, managed to alert the firemen before it was too late. Rescuers eventually managed to dig a hole the size of an oven door into the cellar, through which a plank was inserted. Then, one by one, those entombed were pulled out to safety. However, the family at 14 North View were not so lucky as Brenda’s father, Dennis, soon learned.

Dennis cycled home immediately after hearing about the Savile Town bombing. He had been working the night shift at Newsome’s mill in Batley Carr. He did not know if his wife and daughter had survived. When he finally got through the cordon protecting devastated North View from the general public, he had a heart-stopping moment when:

…the A.R.P. Men told him they had just found two bodies. They had walked over them thinking they were pillows, but they turned out to be Mrs Scott and her daughter Enid who lived next door to us. Mr Scott was working at his shop, he was a cobbler in Thornhill Lees… [8]

Mary Ann Scott (née Platts) was originally from Carlinghow, Batley. Born in 1879 [9], her 61st birthday was only days away. She married boot and shoe repairer Harry Scott at Carlinghow St John’s on 16 April 1906 [10]. Before her marriage she worked as a weaver at Carlinghow mills (at that stage owned by Brooke Wilford & Co.,) and was a prominent member of the Carlinghow church, teaching in its Sunday school. After her marriage the family settled at 14 North View, and this was their home when Enid, their only child, was born on 7 August 1908. Enid attended Savile Town St Mary’s School, and Wheelwright Girls’ Grammar School. Her working life was spent in office and company secretary roles in Ossett. She also was a volunteer at the Dewsbury ARP Report Centre.

Harry was working at his boot repairing business at Brewery Lane, Thornhill Lees, when the attack occurred. That saved his life. On Tuesday 17 December, after a double funeral service at Carlinghow St John’s, it was Harry’s sad duty to walk behind the coffins of his wife and daughter as they were carried to Batley cemetery for interment. No headstone marks their final resting place. But, like Percy Ingham, their names live on in the Westminster Abbey roll of honour and on the CWGC database.

That day marked three more burials – this time all in Dewsbury cemetery. All three men were members of the Dewsbury Home Guard and were employed in Messrs. Crawshaw and Warburton’s Shaw Cross Colliery. The men were in the colliery offices at the former Ridings colliery on Wakefield Road [11], which was wrecked by a parachute mine. A row of terrace houses on Wakefield Road (Sunny Bank, numbers 72 to 82) were also destroyed in the attack. Fortunately the residents there had taken to the communal shelter and all survived. But the Home Guard men were not so fortunate.

Section Leader Sidney Burridge, of 351 Victoria Terrace, Leeds Road, Dewsbury, was a 46-year-old married man. Employed as a colliery deputy at Shaw Cross colliery, it was the same type of job undertaken by his father. Born on 5 July 1894, the son of James Hartley Burridge and wife Jane Elizabeth, he was baptised at St Philip’s church, Dewsbury [12]. It started his lifelong association with the church. It was here, on 8 September 1914, that he married Sophia Squires [13]. And it was the vicar at St Philip’s who conducted his funeral service, with a Union Jack-draped coffin and a Home Guard escort signifying his Local Defence Volunteer role. Outside work, Sidney was a member of Eastborough Working Men’s Club and Dewsbury Rugby League Football Club, both associations represented at his funeral. He left a widow and two children.

Section Commander Ernest Lodge was another of the Home Guard fatalities. He sold house coals and briquettes for Messrs. Crawshaw and Warbuton. Born on 15 November 1893, he was the son of weaver Harry Lodge of Lepton and his wife Elizabeth [14]. Ernest’s mother died around three years later, and on 29 September 1900 Harry re-married at Dewsbury, St Mark’s [15]. His new wife was Sarah Elizabeth Oddy.

Ernest married widow Alice Wilson (formerly Chatwood) at Moorlands Wesleyan Chapel, Dewsbury on 20 July 1929 [16]. The couple both sang with their choir and, at the time of Ernest’s death, lived at 12, Thirlmere Road, Dewsbury.

He too was accorded a funeral with the honour of a Union Jack-covered coffin. Members of the Home Guard lined the path to his grave, which Dewsbury cemetery staff had bordered with evergreen.

Section Commander Wilfred King was the third Home Guard casualty that night. Born on 31 May 1905 at Commonside, Hanging Heaton, he was the son of George and Martha Ann King. A coal hewer at the Shaw Cross pit, he lived with his parents at 457, Leeds Road, Dewsbury.

In a particularly cruel twist of fate, his 28-year-old bride-to-be Mary Glover, of Thornton Street, instead of preparing for her wedding scheduled for later that week, now found herself attending her fiancé’s funeral. She addressed her floral tribute ‘from his broken-hearted and sorrowing sweetheart’. Wilfred’s funeral service was held at the Boothroyd Lane Providence Independent, prior to interment at Dewsbury Cemetery.

But that did not mark the extent of local deaths in the bombing raid of the night of 12/13 December 1940. As I mentioned at the outset, the main focus of the bombing that night was the city of Sheffield with its vital steel and iron works. Arthur Brewer, a long-time resident of Ravensthorpe, was in Sheffield that night.

Arthur was born in Birstall on 30 July 1907. The son of Earl and Mary Brewer, he was baptised at the Mount Zion Chapel at White Lee on 1 September 1907 [17]. Some time after 1911 the family moved to Ravensthorpe, and after leaving school Arthur began a career as a musician, specialising in the drums.

He played regularly at the Town Hall in Mirfield and Dewsbury’s Majestic cinema. He then joined the renowned Paul Zaharoff in London, famed for his international band. Subsequently Arthur went on tour playing in numerous city hotels, including a 16-week stint in Jersey.

In 1935 Arthur married Mary Goddard. For the 18 months prior to his death Arthur was based in Sheffield playing with a band in hotels across the city. In down-times he supplemented his income with lorry driving. Initially Mary stayed with him: she is registered there in the 1939 register. But later she moved to the comparative safety of Dewsbury, and was living with her in-laws at Thornhill Street, in Savile Town. Also with her was her and Arthur’s two children, the youngest only three month’s old at the time of raid. Perhaps it was the birth of the baby which prompted the move.

It is a cruel irony that both Savile Town and Sheffield were simultaneously under a Luftwaffe siege: The security of both Mary and Arthur was at stake that December night.

At about 11.20pm Arthur was in the Marples Hotel in Sheffield with fellow-band member Donovan Russell. The seven-storey Marples Hotel and pub on Fitzalan Square had operated under several names since the 1870’s, initially starting out as the Wine and Spirit Commercial Hotel, and latterly the London Mart. But it was still known as The Marples. And it’s name was to be forever etched in history for the events of that night.

At 11.44pm, as over 70 people sheltered in its cellar, it took a direct hit from a 500lb German bomb. Arthur was believed to be amongst those sheltering. Donovan Russell had a lucky escape – he left Arthur there just 20 minutes before the bomb struck. The entire building collapsed.

It was not until 10am the following day that rescue attempts began, initial assessments being survival was impossible. Amazingly seven people were rescued. But that was all. It is estimated around seventy people died in the building, the biggest single loss of life during the Sheffield Blitz. Arthur was amongst that number. If there was any consolation, death was believed to be instantaneous.

Over the following weeks the site was cleared. 64 bodies were eventually recovered, and partial remains of a further six or seven people. Only 14 were visually identified. Personnal belongings were used in the process of formal identification for most of the others.

As of mid-January the only item belonging to Arthur which Mary recovered were the lenses of his glasses. When probate was granted on 12 March 1942, the entry confirmed identification of his body at the hotel. The entry read:

BREWER Arthur of 34 Thornhill-street Savile Town Dewsbury Yorkshire who is believed to have been killed through war operations on 12 December 1940 and whose dead body was found at Marples Hotel Fitzalan-square Sheffield Administration Wakefield 12 March to March Brewer widow.

Effects £161 5s [18]

I’ve planned this local history tale for some time. I wanted to publish it to coincide with the 75th anniversary of VE Day. Unfortunately, because of the current battle the world faces against the invisible coronavirus enemy, my research was prematurely curtailed. However, I wanted to go ahead with publication as a tribute to our ancestors of 80 years ago. Once some kind of research normality resumes I hope to update this post.

Finally, the Bombing Britain website, which draws together intelligence reports of enemy action on British domestic soil, records only this one direct air raid on Dewsbury. Batley had two recorded air raids. The evening of 12 December into the early hours of 13 December, and one on the night of 15/16 December 1940. This latter raid had no recorded casualties. If anyone does have any memories of these events, or life on the Home Front in Batley and Dewsbury generally, please do contact me.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

It appears the Bombing Britain site covering enemy action over British soil may under-report the bombs which landed over the Batley and Dewsbury area. West Yorkshire Archives produced an ARP Bomb Map for the night of 14/15 March 1941. It can be found at here and includes an unexploded bomb almost opposite what is now Healey Community Centre.

Postscript:

Finally a big thank you for the donations already received to keep this website going.

The website has always been free to use, but it does cost me money to operate. In the current difficult economic climate I am considering if I can continue to afford to keep running it as a free resource, especially as I have to balance the research time against work commitments.

If you have enjoyed reading the various pieces, and would like to make a donation towards keeping the website up and running in its current open access format, it would be very much appreciated.

Please click here to be taken to the PayPal donation link. By making a donation you will be helping to keep the website online and freely available for all.

Thank you.

Notes:

[1] WW2 People’s War archive of wartime memories, bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar, Brenda Hartley, now Haley, Reference A2843750;

[2] Vera May – Batley History Group Facebook Page, Jane Roberts post 19 April 2020;

[3] Geoffrey Whitehead, retired Batley Boy’s High School deputy headmaster, in conversation with Jane Roberts dated 27 April 2020;

[4] Batley News, 21 December 1940;

[5] Geoffrey Whitehead, Ibid;

[6] Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 27 December 1940;

[7] Batley News, 21 December 1940;

[8] WW2 People’s War archive of wartime memories, bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar, Brenda Hartley, now Haley, Reference A2843750;

[9] Birstall St Peter’s baptism register, born on 23 December 1879 and baptised on 25 January 1880, accessed via Ancestry.co.uk West Yorkshire Church of England births and baptisms 1813-1910, original record at West Yorkshire Archive Services, Reference WDP5/1/2/9;

[10] Carlinghow St John’s marriage register, accessed via Ancestry.co.uk West Yorkshire Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1813-1935, original record at West Yorkshire Archive Services, Reference WDP132/1/2/2;

[11] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, Sidney Burridge, Probate Date 27 November 1941 gives the place of death. Accessed via Ancestry.co.uk;

[12] St Philip’s, Dewsbury, baptism register, accessed via Ancestry.co.uk West Yorkshire Church of England births and baptisms 1813-1910, original record at West Yorkshire Archive Services, Reference WDP9/439;

[13] St Philip’s, Dewsbury, marriage register, accessed via Ancestry.co.uk West Yorkshire Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1813-1935, original record at West Yorkshire Archive Services, Reference WDP9/443;

[14] Baptism of Earnest [sic] Lodge, Huddersfield Northumberland Street Methodist Circuit, accessed via Ancestry.co.uk West Yorkshire, Non-Conformist Records, 1646-1985, original record at West Yorkshire Archives Service, Reference KC295/3;

[15] St Mark’s, Dewsbury, marriage register, accessed via Ancestry.co.uk West Yorkshire Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1813-1935, original record at West Yorkshire Archive Services, Reference WDP228/1/2/2;

[16] Marriage register of Moorlands Wesleyan Chapel, Boothroyd Lane, Dewsbury, accessed via Ancestry.co.uk West Yorkshire, Non-Conformist Records, 1646-1985, original record at West Yorkshire Archives Service, Reference C111/207;

[17] Mount Zion, White Lee, Baptism register, accessed via Ancestry.co.uk West Yorkshire, Non-Conformist Records, 1646-1985, original record at West Yorkshire Archives Service, Reference C10/15/1/1/1;

[18] England & Wales National Probate Calendar, Arthur Brewer, Probate Date 12 March 1942; Accessed via Ancestry.co.uk

Sources:

• 1939 Register, accessed via Findmypast and Ancestry.co.uk;

• Batley Cemetery Burial Records;

• Batley News, 14 and 21 December 1940 and 18 January 1941;

• BBC WW2 People’s War, bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar ;

• Bombing Britain website, TNA file series HO203, intelligence reports of enemy action on British domestic soil http://www.warstateandsociety.com/Bombing-Britain ;

• Chariots of Wrath, Sam Whitworth, published 2016;

• Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, https://www.cwgc.org/ ;

• England and Wales Censuses 1881-1911 (various);

• Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 27 December 1940;

• Farnham Maltings website, The Marples Tragedy (Sheffield Blitzm 1940), https://farnhammaltings.com/newsmarples-tragedy/ ;

• Hanging Heaton Golf Club website, https://www.hhgc.org/about-hhgc/

• National Probate Calendar, Herbert Courtney Channon, Sidney Burridge, Arthur Brewer, Enid Scott, Ernest Lodge;

• OS Map is reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under a Creative Commons licence. https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

• Parish Registers – various;

• Sheffield History website, The Marples, https://www.sheffieldhistory.co.uk/forums/topic/98-the-marples/ ;

• The Chris Hobbs website, Marples Hotel, https://www.chrishobbs.com/marples1940.htm ;

• The History of Batley 1800 – 1974, Malcolm H Haigh, published 1985;

• Sheffield Libraries blogspot, Sheffield Blitz: lost eyewitness account from Marples Hotel survivor comes to light in archives, http://shefflibraries.blogspot.com/2017/07/sheffield-blitz-lost-eyewitness-account.html ;

• Western Times, 27 December 1940;

• WW2 People’s War archive of wartime memories, bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar, Brenda Hartley, now Haley, Reference A2843750; Edward Lomax (Dewsbury), Reference A2875782; Ronald Tolson Schofield (Dewsbury), Reference A2843886; and Derrick Sharp (Batley), Reference A2339291;

UPDATE:

This has generated many memories and comments. There are the fantastic ones which have been posted in the WordPress comments section for this post below.

In addition there have been lots posted elsewhere on social media and I have gathered them together here.

• Brian Howgate on Facebook page Batley Photos Old and New wrote: My grandparents lived exactly opposite St Andrews Church in purlwell Hall Road. There house got serverly damaged when the bomb dropped on the church.

• On the same site Lesley Dyer wrote: My grandfather not only worked during the day but was also did his bit as a warden who had to go out and watch out for any incendries dropping which started fires and had to put them out before the German bomber’s came over, it went on for weeks, until one night another warden had told my grandfather that St. Andrews had been hit taking its roof, as a man stood in a shop doorway and the blast/shock wave blew him back into the shop, luckily he survived, the church roof & windows had gone altogether, along with homes in the area had also been damaged too.

• Also on that page Kevin Mcguire wrote: Our next door neighbour had a[n] Anderson shelter which he kept all his gardening gear they did not look that safe to me as a kid there were air aid shelters every where great for exploring and playing Japs and commanders with wooden guns.

• Again on the Batley Photos site Joan Chappell recalled: As a child I went to St. Andrews church. We were told that the reason it had chairs and not pews like most other churches was because it was bombed during the war.

• Also on Batley Photos Jack Dane wrote: ….when we lived on Purwell Crescent I have always had this memory of my mother leaving me outside our gate crying because it was pitch black she ran back into the house to fetch something she had forgotten when we were on our way to our neighbours air raid shelter, the date of the bombing puts me at 3 year old which seems about right if it was that particular night.

• On the Shoddy Matters Facebook Page Christine Lawton wrote: My husband is named after Wilfred king he was a friend of there family.

• On the same page Ian Sewell said: I remember the bunkers up Caulms Wood with the huge stones.

• Also on Shoddy Matters David Wilby wrote: ….growing up [I] remember seeing where the bomb had dropped, up by the farm on Staincliffe hall road, near the top of Deighton Lane.

• And in another Shoddy Matters post Chrissie Chapman wrote: I have lived up Carters fields all my life and was told that the house I own had the gable wall blown down due to a bomb from the war. The wall was rebuilt and I now think, after reading this, it must have been from the bombs that fell on Carters Field . We often played, as children, in the air raid shelter that was on waste land next to the Parochial Hall.

• Linked to Chrissie’s post, on Dewsbury Pictures Old and New Facebook page David Riley said: My aunt Dorie’s gable end was blown up by the bomb in Carters Field had to move into my mum and dads in Northbank Rd near Mullins farm. David also said they lived in the last block of four [houses] facing Healey, Northbank fields by the top of the football pitch. Looking at the 1939 Register, the address for Doris Boden was 173 North Bank Road, Batley.

• Also on the Dewsbury page John Riley wrote: My auntie who lived down Robin Lane, used to find large lumps of shrapnel in the garden which she said came off the exploding AA shells fired from Caulms Wood.

• On Twitter Ghulam Nabi wrote: I attended Birkdale High School in 1974 and top half which was formerly the Girls Grammar school had air raid shelters all around the grounds.. Some of the lads found them and used to skip lessons by hiding in there. As an aside, the Girls Grammar School was Wheelwright, the former school of one of the air raid victims, Enid Scott.