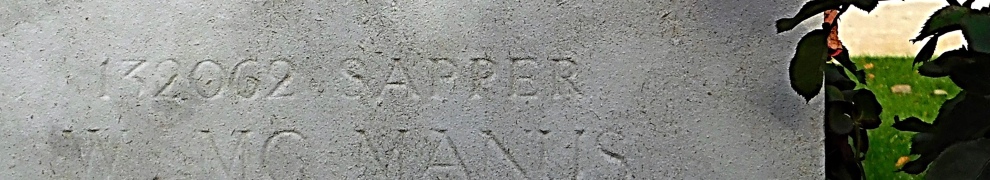

Name: William McManus

Rank: Sapper

Unit/Regiment: 252nd Tunnelling Company, Royal Engineers

Service Number: 132062

Date of Death: 2 March 1916

Memorial: Auchonvillers Military Cemetery, Somme, France

Although the name of William McManus is not inscribed on the War Memorial of St Mary of the Angels, Batley, he is there – instead recorded as William Townsend. A letter from Parish Priest Fr John Lea, dated 20 July 1922 confirms that Sapper William Townsend of the Royal Engineers, who died on 2 March 1916, enlisted as McManus. So there is absolutely no doubt about identification.

Father Lea’s statement is factually correct. William McManus, as he was known for most of his life, was born prior to his mother’s marriage to Thomas McManus. His birth registration is therefore under the name Townsend.

William was born in Batley on the 18 May 1884, the son of Batley-born Mary Townsend.1 Mary, an unmarried woollen weaver, also had a daughter named Sarah Ann, born in October 1879. Like her brother she too was registered as ‘Townsend’ reflecting her mother’s unmarried status. However, there is a possiblity the father of both William and Sarah Ann was Thomas McManus. Unusually the church baptismal register, whilst not noting a father’s name for either child, and clearly recording mother Mary with her Townsend maiden name only, has both children baptised under the name of McManus – although William’s surname is then scored through and replaced with Townsend. The date of this amendment is unclear.

And in the 1891 and 1901 censuses both Sarah Ann and William are entered as daughter and son of Thomas McManus. That being said, in 1911 the census does record Sarah Ann as his illegitimate daughter. But there is a chance this is an enumerator addition. Sarah Ann is aged 32 and the number of years her parents have been married is 25 – and there is a faint line drawn between the two by someone as if linking the discrepancy.

Like Mary Townsend, Thomas McManus was born in Batley. They lived near each other in the 1881 census, at Spring Gardens and New Street respectively.2 Thomas worked as a hewer in the local coal mining industry.

The couple married in late 1886 and, after a spell in a one-roomed house in New Street, eventually settled in the Peel Street area of Batley – number 38 in 1901 and 30B in 1911.

The 1911 census indicates Thomas and Mary had eleven children born during their marriage, four still living. It seems probable that Sarah Ann and William are included in this number, even though born outside of wedlock. In addition, the other children included Thomas, born in 1888 but who died in early January of 1892; John, born in May 1890; James (the name under which he was baptised and is recorded as in the censuses, but who seems to have been registered with the name Thomas), born in December 1891; Frank, born in August 1893, but who died in May 1895; Michael, born in the spring of 1895, and who died in April 1896; and Margaret (Maggie), born in October 1898 and who died in February 1902. Mary also had another child born before her marriage – a son born in November 1882, registered as Thomas Townsend. Does the name of this baby boy hint at his father? The infant died the following March, age four months. I have still to identify the remaining two children.

By 1901 William was also working in the coal mine, as a hurrier. However, in July 1902 he attested in Leeds with the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, adding a couple of years to his age, claiming to be 20 years and six months old. It was only a brief stint of 179 days, all based in this country, as he was granted a free discharge in January 1903. But we do have a description of the 18-year-old William from these records, standing at 5’ 6” (a ¼ inch below his 1915 height) weighing 126lbs, with blue eyes, brown hair and a fair complexion. He also had a scar on his nose and forehead.

William returned to Batley and resumed his work in the pit, graduating from hurrier to hewer.

Saturday 4 March 1905 was a mild day for the time of year, fair, though overcast with the threat of heavy drizzle never far away. It was on this day that William stood before Father Lea in St Mary’s church to celebrate his marriage to 21-year-old rag sorter Maggie Elizabeth Redgwick. She was a diminutive young woman at five feet tall, with ginger hair and blue eyes – the colouring hinting at her mother’s Irish heritage. She was the daughter of Arthur Redgwick and his wife Mary Ann (née Cafferty). Both Maggie’s father, and brother Thomas, were to lose their lives in the war. But that was for the future. Today was a day for the uniting of the McManus and Redgwick families. A day of hope and promises for the future. The marriage witnesses were William’s sister Sarah Ann, and his uncle James Daley. The marriage was registered under William’s official Townsend surname, again another reason why Father Lea was able to pen his letter of July 1922 confirming that William Townsend was the correct name for William McManus. And why he is recorded thus on St Mary’s War Memorial (although he is McManus on Batley’s town Memorial).

The census of 2 April 1911 records William and Maggie Lizzie living alone in a two roomed house, the address being a familiar one for the McManus family – 38 Peel Street. William still worked as a coal miner (hewer) and Maggie was still employed as a rag sorter in a woollen mill. No children had been born during the six years of their marriage. The enumerator completed the form, as neither William or Maggie could write. He listed the couple’s surname as Townend. The address schedule indicates William used the shortened name form of Willie. It is an unremarkable entry, hinting nothing of any underlying tensions. Other than a brief spell served by William in Wakefield Prison for debt in June 1907 there is nothing.

Yet by 26 July 1911 Maggie had reverted to her maiden name of Redgwick, as she boarded the Dominion at Liverpool, bound for Philadelphia and her aunt, Mrs Berry. She gave her last permanent residence in England as Batley Carr, so not the marital home. And equally tellingly she stated her mother was her nearest relative back in England. Maggie never married again and died in 1956. Although she never had children of her own she acted as foster mother to her nephew Thomas John Redgwick, son of her sister Mary. Born in May 1916, with a tragic symmetry he died in France, serving with the US Army, on 16 July 1944, 28 years after his uncle Thomas was killed in action during the First World War in that same country.

Perhaps the ending of the marriage was the catalyst for William leaving Batley. By 1913 he was working near Barnsley at Darfield Main Colliery, Wombwell. Prior to attesting, on 22 September 1915, he lodged with the Woodhead family at Darfield Bridge. Interestingly on his attestation papers he stated he was unmarried. No details of his marriage are mentioned on his descriptive report on enlistment. And he lists his next of kin as Thomas McManus.

Described as “a very charitably disposed man, and ever ready to help those less fortunate than himself”3 the colliery manager, John William Halmshaw of the Mitchell Main Colliery Company, the company which owned Darfield Main at this point, wrote the following testimonial on 23 September 1915:

This is to certify that W[illia]m McManus has been employed at the above coll[ier]y for over two years as a miner, and we have always found him to be a good worker and throughly used to any pit work he took in hand.

This testimonial was needed because William’s intended unit was the Royal Engineers. More specifically he was being recruited for the subterranean branch of warfare, tunnelling. It was an idea championed by engineer, and former MP, Major John Norton-Griffiths. With stalemate above ground, the Germans had turned to underground attacks by the end of 1914, digging tunnels under British positions then blowing mines to try break the deadlock.

By February 1915 the decision was taken by the British side to form dedicated Tunnelling Companies, as part of the Royal Engineers. The men were specifically recruited for this work because of their unique skills – men who had experience of working below ground, for instance in creating the London Underground, the sewer network or as coal miners.

The idea was to drive underground tunnels towards the enemy lines, pack the chamber at the end with explosives, and then blow a mine beneath the enemy positions. Before they could regroup, this tactic would allow the infantry on the surface to rush to the newly created crater and capture it, gaining an advantage above ground.

The mine, created by the 252nd Tunnelling Company, under German front line positions at Hawthorn Redoubt was fired 10 minutes before the assault at Beaumont Hamel on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916. 45,000 pounds of ammonal exploded. The mine caused a crater 130 feet across by 58 feet deep – Photo by Ernest Brooks – https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194574 – © IWM Q 754 – IWM non-commercial licence

And

Hawthorn Ridge Crater (created by the 1 July 1916 detonation, and a second on 13 November 1916) and Lochnagar Crater (created by another 1 July 1916 mine) photographed in 2019 – by Jane Roberts

Tunnelling was tense, dangerous work – undertaken 24×7, in silence. Someone digging out the tunnels, another packing the bags of spoil, whilst another on the team would ferry it to the shaft to be removed. Not only was there the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning in the foetid, dark, cramped, claustrophobic, damp and often wet tunnels, there was also the unrelenting psychological element. Because also working underground, often within very close proximity, was the enemy, whose objectives included destroying your tunnel before it became viable and a danger to them.

There was frequent stopping to listen, or to still any sound, if the enemy was thought to be near. The slightest noise – an inadvertent cough, scrape or sneeze – would alert them of your presence. And conversely you would be on the alert for enemy tunnellers.

At any second they could detonate a charge, to create a camouflet, bringing down your tunnel, potentially crushing you to death or entombing you alive. In this underworld of mining and counter-mining, there was also the constant risk of the enemy breaking into your position, with brutal hand to hand fighting ensuing in the dim tunnels and chambers. So not only was the job of tunnelling a skilled one, it needed a calm head and nerves of steel.

And to reflect the skills and temperament required, there was a financial incentive. William Townsend enlisted as a Tunnellers Mate, on the standard rate of 2s 2d per day. A skilled tunneller earned significantly more. In comparison an infantryman in the trenches pay rate was 1s 3d per day.

And because tunnellers, by dint of their civilian occupation, already had the skills for the job, the training period was far shorter. By the 4 October 1915, less than two weeks after enlisting, William was leaving Chatham bound for France. Once there he transferred to the newly formed 252nd Tunnelling Company at Rouen, under the command of Captain Rex Trower. By the beginning of November they were in situ on the Somme, in the Hebuterne-Beaumont-Hamel sector. And by 6 November 1915 he was remustered as a tunneller. His service records contain the following note, dated 16 January 1916:

Certified that No 132062 Sap[per] W McManus possesses necessary qualifications for rating as Tunneller. He has been mustered accordingly with effect from 6 November 1915

In terms of location, the trench map below illustrates the main area where the 252nd Tunnelling Company operated whilst William served with them. Auchonvillers, where he is now buried, is to the left. Redan is clearly marked at the top centre of the map.

Scale: 1:20000 Edition: 2B Published: 1916. Trenches corrected to 28 April 1916 – National Library of Scotland, under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC-BY-NC-SA) licence

The ground in which the 252nd tunnelling company worked comprised of hard chalk and flint. This had to be painstakingly and silently prised out. In parts it was necessary to do this by wetting the face and working the chalk out with bayonets. It could be very slow progress.4 Extracts from their Unit War Diary gives a flavour of the work, and constant tension under which it was undertaken.

Toutencourt 12-11-15 The two shafts were in chalk 28’ and 30’ respectively on this date whilst No5 Redan has been cleared to 60’ and the enemy were heard working…

And

27-11-15 to 28-11-15 The shafts in the Redan were now down 121’ and 122’. In No2 shaft at a vertical depth of 65’ a station was being cut when enemy mining was heard. At 5 p.m. Capt. Trower went to the mine and ordered everything to be held ready. The enemy were working to the South East….Enemy continued to work all night and we put the tamping down the mine. At 8 a.m. Captain Trower reported to Col. Jones C.R.E 4th Division and the charge was put in and tamped. 980lbs of guncotton was used…the mine was tamped and ready at 4 p.m. The shaft was filled with sandbags to within 50’ of the surface and the charge successfully exploded at 4.30. The enemy were heard just before we left the mine…

Redan R2 – 21-12-15 Enemy exploded mine N of main gallery, destroying RII(2)(1). Slightly damaged main gallery. No casualties occurred. Men withdrawn 10 minutes before blow, owing to bad air…

Redan R2 – 27-12-15 Capt Logan, RAMC Gas Expert, while taking samples of gas was overcome by CO gas but quickly recovered…

Redan R2 – 29-12-15 Sounds of hostile working are again clearly heard. Made preparations to charge at 50ft along main gallery so as to be in readiness to explode on near approach of enemy…

Redan Enemy Explodes 8-1-16 At 3.30A.M. The Enemy exploded a large camouflet to the South East and above the chamber of RIII which was broken in. The South drive was also completely smashed in and two men were cut off and shut in the face of the South drive. RIII(1). Rescue work was immediately started, the whole company taking shifts of three to five minutes. A new drive was started from the shaft through unbroken ground and 22ft driven through solid chalk to the crushed drive. 48ft was then driven through broken ground and the two men taken alive from the end of the tunnel after being entombed for 21 hours. The company made 70ft in 21 hours 22 of them being thrown solid chalk…

Redan 10-1-16 2nd Lieut A.W. Kidd overcome with nerves and sent to England…

Redan 17-1-16 Enemy were heard working very close to and above RIII(1)(1) and a charge of 2600 guncotton was rushed in, tamped and fired at 6.23A.M. The enemy party were heard in the mine just before our charge was fired and the difference classes of work they were doing could be distinguished with the naked ear. Enemy piled over shells, rifle grenades and trench mortars after the explosion…

Redan RII 24-1-16 The enemy blew a large camouflet at 7.20A.M to the South East of RII(1). Very little damage was done to the gallery but the end was closed in. One man was killed underground and one wounded slightly. This is the first mining casualty in the company…5

These excerpts are typical, illustrating the day by day strain of listening out for the enemy, coupled with the risk that the enemy may have had heard you. The issues with bad air are mentioned. But there is also the camaraderie – typified by the Herculean effort to reach their entombed chums after an explosion. This was also apparent in March 1916, but more of that later.

As an aside, that first mining casualty suffered by the 252nd Tunnelling Company – as referred to in the 24 January 1916 entry above – was Sapper Edwin Orr, whose widow lived at Hartshead.

During his time with the 252nd Tunnelling Company, William was admitted to hospital on 2 January 1916. The reason is not indicated and the War Diary offers no real clues. The entry for that day does refer to the enemy blowing up a mine under the south corner of Redan at 5.30am, but it goes on to say it was quite small and there were no casualties.

Between the 5 to 12 February 1916 William had a period of leave, when he took the opportunity to visit his friends in Darfield. However, this landed him in trouble. He was late reporting back for duty, overstaying his leave by one day. His records state he returned on 14 instead of 13 February. For this he not only forfeited one day’s pay, but he was sentenced to 14 days Field Punishment No 2. The 1914 Manual of Military Law defined it thus:

… 2. Where an offender is sentence to field punishment No. 1, he may, during the continuance of his sentence, unless the court-martial or commanding officer otherwise directs, be punished as follows:

(a) He may be kept in irons, i.e., in fetters or handcuffs, or both fetters and handcuffs; and may be secured so as to prevent his escape.

(b) When in irons he may be attached for a period or periods not exceeding two hours in any one day to a fixed object, but he must not be so attached during more than three out of any four consecutive days, nor during more than twenty-one days in all.

(c) Straps or ropes may be used for the purpose of these rules in lieu of irons.

(d) He may be subjected to the like labour, employment, and restraint, and dealt with in like manner as if he were under a sentence of imprisonment with hard labour.3. Where an offender is sentenced to field punishment No. 2, the foregoing rule with respect to field punishment No. 1 shall apply to him, except that he shall not be liable to be attached to a fixed object as provided by paragraph (b) of Rule 2.

4. Every portion of a field punishment shall be inflicted in such a manner as is calculated not to cause injury or to leave any permanent mark on the offender; and a portion of a field punishment must be discontinued upon a report by a responsible medical officer that the continuance of that portion would be prejudicial to the offender’s health….

Just over a couple of weeks after his sentencing, William was killed in action below ground, the result of an enemy mine explosion. The Unit War Diary records the events of that day:

Redan, 1 March 1916. The enemy blew a large camouflet at 11.57 a.m. on this date directly East of RIII (2) (3) and by it destroyed 62 feet of our gallery. Sgt Dean and two sappers were working in the face at the time and were killed. It was impossible to get near the bodies. The strength of the German charge was probably about 3000 lbs H[igh] E[xplosive]6

Similar to the rescue described on 8 January 1916, once more desperate efforts were made to reach the trapped men. But this time not all were saved. As a result of the attempts two DCMs were awarded for the gallantry showed in the mines that day. Sergeant Edward Brown’s7 citation was for:

…conspicuous devotion to duty in rescuing men who had been incapacitated after the blowing in of a camouflet. Later he re-entered the mine to rescue incapacitated tunnellers, and worked strenuously till exhausted to extricate men who were entombed in a destroyed gallery.8

Sapper John Burns’ citation read:

For conspicuous devotion to duty and disregard of danger. Following the explosion of an enemy mine, he rescued an injured comrade, and later carried out two others. Sapper Burns then returned to aid the rescue work under very dangerous conditions.9

The two men who died with William McManus were 26-year-old Sergeant Albert Dean, a Staffordshire miner from Talke, who had transferred from the 6th Royal Fusiliers.10 And Sapper James Bernasconi, a 32-year-old from Holbeck, Leeds. Prior to enlisting as a Tunneller’s Mate in September 1915 James worked for the Mickelfield Coal and Lime Company. He left a widow, Ethel, and a four-year-old son Frederick. His widow made a poignant request respecting his effects. In a letter it was stated that:

…her husband had a watch which she would like for her little boy if it had been found and his Rosary Beads.11

There is no indication as to whether these were returned.

Although the explosion took place on 1 March, the date of death for the three men is recorded as 2 March. All three are buried in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery in a shared row, with James and William’s names on the same headstone.

On 3 April 1916, less than a month after learning of her son’s death, Mary McManus died too. She was buried in Batley Cemetery on 7 April.

William’s father Thomas, (and this relationship is as stated on his pension card) was awarded 5 shillings a week dependant’s pension on 3 October 1916 as a result of William’s death. However, this payment was short-lived. Thomas died at the end of October 1916.12 He too was buried in Batley cemetery, on 1 November. In the space of eight months the McManus family had suffered three deaths. William’s medals, the 1914/15 Star, British War and Victory Medals, were therefore sent to his brother John.

In addition to St Mary’s, William is remembered on Batley War Memorial, the Darfield Village Club Roll of Honour and Darfield Main Colliery Roll of Honour.

The work of the 252nd Tunnelling Company continued. The most famous mine laid by them was that of Hawthorn Ridge, started just after William’s death, and which was detonated at 7.20am on 1 July 1916. This marked the opening action of the Battle of the Somme. Its detonation was iconically captured on film by Geoffrey Malins, and can be seen at around the 7 minute 55 second mark of the attached film, which is held by the Imperial War Museum.

Notes:

1. Baptism register;

2. 1881 Census – References RG11/4546/23/39 and RG11/4546/5/4;

3. South Yorkshire Times – 18 March 1916;

4. 252 Tunnelling Company Royal Engineers Unit War Diary, 1915 Oct – 1919 Apr, The National Archives, Reference WO 95/406/3;

5. Ibid;

6. Ibid;

7. The London Gazette citation gives his rank as Second Corporal;

8. The London Gazette, 14 April 1916, Supplement 29548, Page 3987;

9. Ibid;

10. The CWGC headstone incorrectly records his age as 29. Soldiers Died in the Great War gives his birthplace as Butts End, whereas the census states Talke;

11. WO363 Burn Records;

12. The Pension Card states Thomas’ date of death was 28 October 1916, whereas the death notice in the Batley News of 4 November 1916 gives it as 30 October 1916.

Sources (other than above):

• 252 Tunnelling Company Unit War Diary;

• Batley Cemetery Burial Register;

• Batley News;

• Commonwealth War Graves Commission;

• England and Wales Censuses – 1881 to 1911;

• FindAGrave;

• GRO Indexes;

Manual of Military Law … 1914. London: H.M.S.O., 1914 (reprinted 1917).

• Marriage Certificate;

• Medal Index Card and Award Rolls;

• Migration Records;

• Pension Ledgers and Index Cards;

• Service Records;

• Soldier’s Effects Register;

• US Census – 1920 and 1930;

• US Social Security Indexes;

• WW2 Draft Registration Cards for Pennsylvania;

• WW2 US Veteran Compensation Application Files, Pennsylvania.

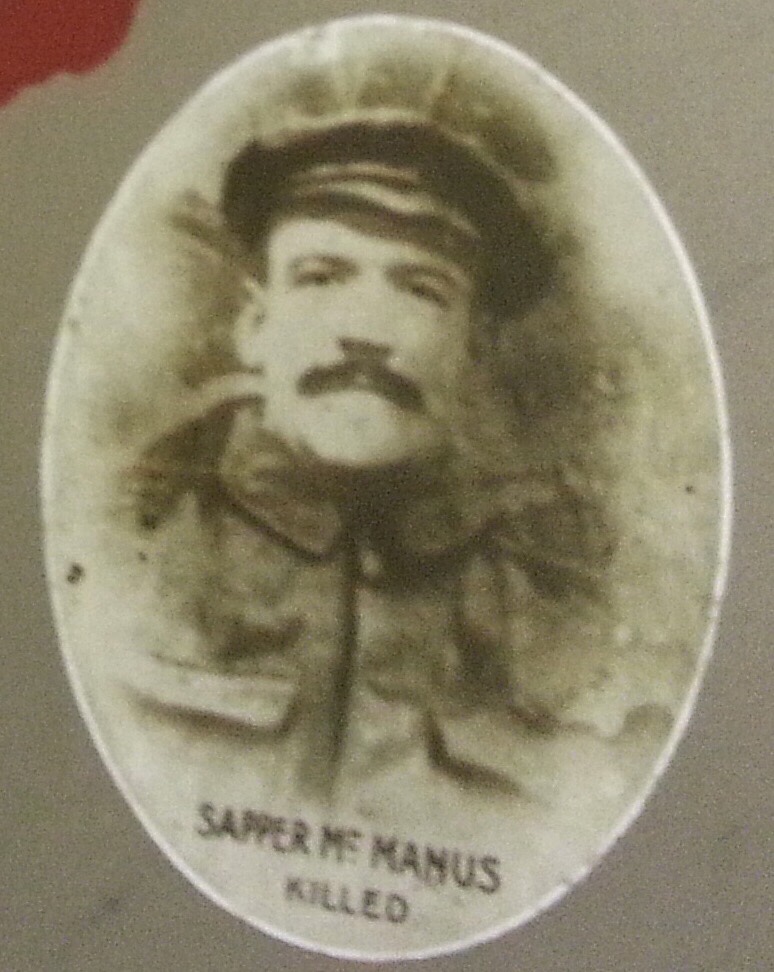

With thanks to Linda Hutton for permission to use the Darfield Village Club Roll of Honour image of William McManus (see photo credit for details)

Footnote:

I first visited Auchonvillers Military Cemetery in September 2009 on a group visit organised by KOYLI Battlefield Tours. The day is etched in my memory.

I was already researching the St Mary’s men, and already visiting graves and memorials, photographing headstones and inscriptions. But at this stage I had not come across Father Lea’s letter and was working on the assumption that the St Mary’s War Memorial William Townsend was William Frederick Townsend.

I’ve always felt comfortable visiting cemeteries, but on this occasion I had a distinctly uneasy feeling and, quite upset, I left before the organised visit ended, returning to the coach to await the rest of the group.

It affected me so much that once I returned home I spent ages looking at the names of those buried there to see if I could find any connection. I could not. William McManus has only a brief entry in the CWGC burial register, no address or family details for me to latch onto, and not a name familiar to either my family history or War Memorial research. But the disconcertion stayed with me so much that on several subsequent independent visits, after explaining what had happened to my husband, we deliberately steered clear of a return to Auchonvillers Military Cemetery.

However, I finally did go back in 2019, after I discovered that the cemetery was the final resting place of St Mary’s man William McManus. And this time I had the same sense of peace that I would have visiting any other cemetery.