22 August 1918 marks the centenary of the death of Guardsman Clement Manning. The 22-year-old lost his life whilst serving with Number 1 Company of the 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards. His Soldiers Died in the Great War record gives his birthplace as Batley, Yorkshire. This was stretching the truth – by over 600 miles. Whilst he did live in the town in the years leading up to the outbreak of war, he was actually born on 13 November 1895 at Niederschöneweide, a German industrial town which subsequently assimilated with Berlin.

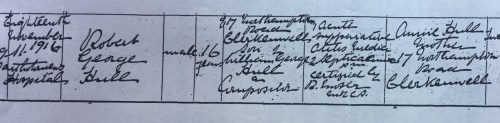

Clement’s parents were Michael Manning from Kilkenny and Mary Eliza Manning (née Waterson), also known as Muriel, from Triangle, Yorkshire. The couple married in 1881 and had 12 children in total, seven who were still living by the time of the 1911 census. Their eldest son, John Tynan, was born in Batley in April 1883. The other children listed in the 1911 census included Michael Wilfrid (born March 1886), Cecilia (born January 1889), Hester (born February 1891), Cecil Tynan (born July 1893) and Walter Nicholas (born August 1900). All these younger children shared the same birthplace – Niederschöneweide (written as Nieden Schonweide in the census). Of the five children who had died before the 1911 census I have traced three to Germany: Lillian (born October 1887 and died April 1889); Henriette (born October 1894 and died February 1903); and Helene (born March 1897 and died the following month).

The key to the Manning children’s German birthplace was their father’s occupation. In the 1881 census, prior to his marriage, Michael worked as a rag grinder (woollen). Batley mill owner John Blackburn opened a shoddy mill in 1869 in Niederschöneweide. Another woollen factory, Anton Lehmann’s, followed in 1881. English employees with expertise in shoddy manufacturing were employed in these factories and they, along with their families, moved into the community. Consequently hundreds of Batley people are said to have left their native town and found very lucrative employment here. By the mid 1880’s there was quite a substantial Yorkshire colony in Berlin, with Yorkshire men working for either John Blackburn or Lehmanns, so it is probable that this was the magnet which pulled the Mannings to Germany. Education was at the village school, the Gemeinde-Schule, but English was spoken at home and at Sunday School, so the children would have had the advantage of being bi-lingual. Batley Feast was celebrated, as were festivities for Queen Victoria’s Jubilees in 1887 and 1897.

Clement spent the first seven years of his life in Germany. When the family came back to Batley they returned to worship at St Mary of the Angels R.C. Church and Clement attended the associated school to complete his education. Their 1911 census Batley address was on Bradford Road with 15-year-old Clement described as a butcher boy. He continued in this field of employment because, before enlisting, his employers were the Batley branch of the Argentine Meat Company. He also played football with the Batley shop assistants team.

Clement enlisted with the Grenadier Guards in February 1915, the third of the Manning boys to enter military service. Cecil attested with the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry in February 1908 but proved unsatisfactory and was discharged days later. Perhaps it was the fact he was not yet 15, rather than his declared age of 18 years and six months, which played the deciding factor in his swift departure. Undeterred, in July 1911 he tried his hand again joining the Royal Navy, and in this pre-war era once again gave his birthplace as Berlin. His service records show at the age of 18 he already stood at 5ft 11½ inches. During the war he served on ships including Cruisers HMS Berwick and HMS Endymion, seeing action in the Dardanelles on the latter. He ended the war serving on the Dreadnought battleship HMS Orion.

Michael Wilfrid enlisted with the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry at the beginning of September 1914 but quickly switched to the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve to serve with the Royal Naval Division (RND). The RND was formed because there was a surplus of Royal Navy and Royal Marine reservists and volunteers. With insufficient ships to accommodate these men they were not needed for service at sea, so the men who served in the RND fought on land alongside the Army. Michael’s Record of Service has no birthplace recorded, but it shows he too was a tall man, standing at just under 6ft 1in. His war came to an abrupt end in the RND’s hastily prepared and ill-equipped part in the Defence of Antwerp in early October 1914. By 9 October he was a Prisoner of War, along with around 1,500 other RND men.

Döberitz Camp PoWs

Letters home from Michael appeared from time to time in the local newspapers. On 8 May 1915 the Dewsbury District News reported that he was being held at Döberitz, acting as an interpreter in a German military hospital. Ironically this camp was a little over 20 miles from where Michael spent his childhood. His letters show a desperate need for food and other provisions. This proved a recurring theme in his letters home. In one to his parents he wrote:

“Please don’t leave off sending cocoa, bread, cakes, bully beef, and other things”.

In another letter he says:

“I have got all your parcels but no cigs. You know, if you cannot get food or cigs through, you can always send money, and then I can buy what I am short of. With the money you have sent, I shall be able to last another month, and then perhaps you will send some more. In good health. Please send cocoa and biscuits”.

The Dewsbury District News published a further letter on the 24 July 1915, Michael again writing from Döberitz:

“Please send me each week one loaf, quarter pound of cocoa, a tin of milk, and a few cigarettes. There is no charge for sending them, and you will never miss them in your weekly bill. We are having plenty of warm weather, and a little rain. I suppose it will be the same at home. How are our local Terriers feeling the strain? Are the county or local cricket matches played? I have just got 8 marks 50 pfennigs. That is what your 7s 6d postal order is worth here. I hope you will send me some more money and parcels every week – tea, cocoa, and one loaf of bread and biscuits. Salmon, or a tin or two of lobster, would not be amiss. I have a little garden were I grow radishes, lettuce and tomatoes. I live a very quiet life.”

On 25 October 1915 Michael Manning (senior) died, five days after Clement embarked for the Western Front with the 3rd Grenadier Guards. A couple of months later a fourth Manning brother, John Tynan, signed his attestation papers under the Derby Scheme. He too inherited the family tall genes, being another 6 footer. A mechanic by trade he eventually received his call up to join the Army Service Corps (Mechanical Transport) in March 1917, going out to France the following month. But as John was going overseas Clement was back home in England after taking part in the 3rd Grenadier Guards’ action on the Somme in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette.

The summer of 1916 was a particularly anxious time for the Manning family, who were receiving a series of updates from the captive Michael Wilfrid. These coincided with another wave of countrywide reports about the neglect and ill-treatment of Döberitz prisoners as illustrated by the case of Pte Tulley, a Royal Marine captured at Antwerp. 14 stone when taken prisoner he was sent back to England to die weighing only 5 stone. His case was widely reported in April 1916. His death, two weeks after arrival home, was attributed to exposure and insufficient food and clothing whilst held prisoner in Germany.

Extracts from Michael’s letters featured in the 12 August 1916 edition of the Batley News and supported the claims, by revealing more about the conditions he was enduring with a particular focus on the need for food. In one dated May 1916 he wrote:

“I hope you are sending my parcels every week. Please send everything – bread, meat, sugar, tea, milk and fish. I hope this beastly war will finish before long. Are you getting ready for my coming home? I hope to see everyone I know then”.

A sarcasm-laden letter postcard dated June 1916 revealed he had indeed undertaken a move – but further east to German-held territory in Russia. The move was a direct German reprisal against the British who in April 1916 had sanctioned the use of around 1,500 German POWs to work in France.

“I have just finished a 2½ day railway journey, and after travelling that time it is a pleasure to rest and be able to stretch your limbs again. You will no doubt wonder why I have had to leave the hospital. Well, you see 2,000 of the prisoners are required for work, and I with the other five sanitates at Rohrbeck Hospital had to come with the party to act as sanitates here. I am pleased I could come with them. It is a splendid change, and we get to see the world. In years to come I and others will look back upon these times and thank the Germans for these trips”.

And, in addition to Michael Wilfred’s move, there was the Flers-Courcelette injury to Clement. Commencing on 15 September 1916, this engagement during the Battle of the Somme marked the first use of tanks. The 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards unit war diary recorded prior to zero hour on 15 September:

“the ‘tanks’ which were allotted to the Division could be heard making their way up in rear of us”.

It also recorded the numbers of killed, wounded or missing when roll call was taken at the end of 15 September 1916: 413 officers and men. This was the largest single day’s loss for this battalion in the war. Amongst their dead was Lt Raymond Asquith, son of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. It appears Clement was amongst those injured, receiving what was recorded as a gunshot wound to his left arm. He was evacuated back to England on board the HMHS Asturias on 17 September 1916.

Incidentally six months later, on 20 March 1917, en route from Avonmouth to Southampton this hospital ship was torpedoed by a German U-boat. Fortunately she had already unloaded her cargo of wounded, otherwise the casualty count would have proved far higher. Nevertheless in excess of 30 crew, including two nurses, perished. The ship was declared a total loss.

Back in England Clement recovered from his Battle of the Somme injury and was assigned to the Regiment’s home-based 5th (Reserve) Battalion to recuperate. This proved longer than anticipated with three further hospital admissions recorded whilst with the Reserve unit. On 28 November 1916 he suffered an accidental foot injury and concussion. He was not discharged from hospital until 14 February 1917. A week later he was admitted once more, this time suffering from rheumatic fever. It was a shorter stay, with his discharge date recorded as 21 April 1917 – three days prior to brother John going overseas. There was a further admission on 20 June 1917 when enteritis struck Clement down. He was able to undertake light duties from the end of July 1917, but it was not until 5 September 1917 that he was considered fully fit to return to duty, ultimately going back to the Front to rejoin the 3rd Battalion once more.

Clement was killed in action in the last 100 days of the war, with the Germans in retreat. The 21 August 1918 marked the start of the Second Battle of the Somme. From the 21 to the 23 August 1918 the 3rd Grenadier Guards were involved in what became known as the Battle of Albert, a phase of this battle, as part of the Third Army under the command of General Byng. The battalion were part of the Guards Division, VI Corps.

The official history of the Grenadier Guards describes the events of the battle, as does Reminiscences of a Grenadier by E.R.M. Fryer, who was in command of 1 Company, the company with which Clement served, for the crucial period.

On the 20th August 1918 they took up its assembly positions East and South East of Boiry. Their orders were to attack Moyenneville. The attack commenced in the early hours of an initially extremely foggy on 21 August. The fog veiled the Guards Division as they advanced towards their first objective. However, later it lifted, exposing the attack to enemy artillery and the inevitable accompanying hail of German machine gun fire. Surprisingly, the Guards reportedly incurred few casualties during this stage of the battle. By midday they had secured all their objectives, including Moyenneville, the 3rd Grenadier Guards taking a chalk pit to the south east of the village, whilst a platoon belonging to the battalion had advanced as far as the outskirts of Courcelles. By noon on the 21st V1 Corps had attained almost all of its objectives and were positioned along the Arras—Albert railway line where they came under intense artillery fire. At this stage of the battle it had been intended for tanks and the cavalry to take over from the infantry to exploit the situation, but none had appeared. Unexpectedly Number 1 Company of the 3rd Grenadier Guards, who were intended to have a reserve role that day, played a key part in events.

Captain Fryer described the aftermath of the 21 August and the events of the 22 August as follows:

That night passed off fairly uneventfully; we were content with our day’s work, the Commanding Officer had praised us, and we heard that the higher authorities were well pleased, and so we were contented. It is hardly necessary to say the men were wonderful they always were. Were it possible to mention them all by name in this book I would do so…..No one was more loyally served by the men under him than I was, from the C.S.M. to the youngest guardsman;…….

On the morning of the 22nd at dawn we were just getting ready to stand to arms in the ordinary way when the Germans opened a terrific barrage on us, and a messenger arrived from the front line to say the Germans were coming over; we raced out from our quarry, ran the gauntlet of innumerable shells, and reached the railway safely;…….

Someone on our right sent up the S.O.S., our artillery put down a very good and accurate barrage, and all was quiet; it was impossible to get communication with our front platoon during this time, and we had no idea how they were faring……it was an organised counter-attack with the idea of [the Germans] regaining all they had lost the day before. It failed completely, …..

The rest of that day was very trying; we were all tired, and the Germans shelled us relentlessly all day, and also trench-mortared us; they got on to our quarry, and it became far from healthy….

Sometime during the day of 22 August 1918 Clement was killed. At the time the local newspapers reported Clement’s death, his brother John was serving with the ASC in France; Michael was still a prisoner of war; Cecil was in the Royal Navy on board HMS Orion.

John, Michael and Cecil all survived the war. Michael was the first to return to his home in Providence Terrace, Bradford Road, Carlinghow after more than four years captivity. He arrived in Leeds on Christmas morning 1918, having come from Copenhagen via Leith. An account of his time as a prisoner of war appeared in the Batley Reporter and Guardian on 3 January 1919 as follows:

“…..of his stay in Germany Seaman Manning says the German doctors treated them well, and he believed they would have been treated even better if the authorities would have allowed it. The doctors bandaged and attended British soldiers in a similar manner to their own. Seaman Manning, who was acquainted with the German language, often performed the duty of interpreter between the doctors and his fellow-prisoners. As for the rest of the Germans, Seaman Manning says they behaved like uncivilised creatures. A favourite trick of the German nurses was to first spit into a glass of water and then hand it to the prisoners. At other times when a glass of water was asked for by the prisoners the nurses would hold it just out of reach, then either dash the water into the prisoners face or pour it on the floor. About 5,000 prisoners were sent on a reprisal party to Russia and made to work behind the lines in range of the Russian guns. The reason for this was that the Germans alleged that the Allies were [using] the German prisoners behind the lines on the Western Front. The “reprisal party” were working behind the lines for 18 months, three months of that time being spent in some of the coldest weather ever known. Complaints of poor food and clothing and frost bite etc received no attention. At the time of the signing of the Armistice many prisoners were working in coal mines, and the Germans told them they must continue working in order to provide coal to work the trains. The conditions of the mines was most terrible and the prisoners refused to work. Threats were used, and finally machine guns were brought up in a vain effort to frighten the prisoners into submission. In regard to food, Seaman Manning says that it was often not fit to eat, and often when the prisoners were starving they refused to eat the food. When parcels began to arrive from home German food was rarely eaten, all the prisoners required at this time was sufficient air, light and cooking accommodation and this was often lacking. During the time he was in the internment camp Seaman Manning came across prisoners of all allied nationalities. The camps were often overcrowded and in a filthy condition. Asked his opinion of the [revolution] Seaman Manning says that he thinks it is a humbug meant to throw dust into the Allies eyes. The German people are trying to make it appear, he says, that it was all the rulers fault, [whereas] all the German people were “for” the war. When Seaman Manning left Germany the Germans said they would soon be in England on business. Seaman Manning adds that he would like to [meet some] of the brutes in England”.

John was demobilised in October 1919 whilst Cecil left the Navy in June 1921.

Clement was awarded the 1914-15 Star, Victory Medal and British War Medal. In addition to St Mary’s, he is also remembered on the Batley War Memorial and the Memorial at St John’s Carlinghow. He is now laid to rest at Bucquoy Road Cemetery, Ficheux, France. This is a concentration cemetery with graves being brought in from the wider battlefield and smaller cemeteries in the neighbourhood post-Armistice. These re-burials included Clement.

Sources:

- Soldiers Died in the Great War

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission

- Medal Index Cards & Medal Award Rolls

- General Register Office Indexes

- 1881 and 1911 Census (England & Wales)

- Dewsbury District News

- Batley News

- Batley Reporter & Guardian

- Landesarchiv Berlin; Berlin, Deutschland; Personenstandsregister Geburtsregister; via Ancestry.com. Berlin, Germany, Births, 1874-1899 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

- Landesarchiv Berlin; Berlin, Deutschland; Personenstandsregister Sterberegister ; via Ancestry.com. Berlin, Germany, Deaths, 1874-1920 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

- Oswego, New York, United States Marriages via FindMyPast and FamilySearch Film Number 000857423 (Walter Nicholas Manning)

- The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Manifests of Alien Arrivals at Buffalo, Lewiston, Niagara Falls, and Rochester, New York, 1902-1954; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787 – 2004; Record Group Number: 85; Series Number: M1480; Roll Number: 090 via Ancestry.com. U.S., Border Crossings from Canada to U.S., 1895-1960 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. (Walter Nicholas Manning)

- The National Archives, Royal Navy Registers of Seamen’s Services, Ref ADM 188/654/3883 for Cecil Tynan Manning via FindMyPast

- The National Archives, Admiralty and War Office: Royal Naval Division: Records of Service, Ref ADM 339/1/23549 for Michael Wilfrid Manning via FindMyPast

- 1914-1918 Prisoners of the First World War, ICRC Historical Archives: https://grandeguerre.icrc.org/

- The National Archives War Office: Soldiers’ Documents, First World War ‘Burnt Documents’ Ref WO 363 – John Tynan Manning via Ancestry.co.uk

- 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards, Guards Division, 2nd Guards Brigade, 1 July 1915 – 31 January 1919 – TNA WO 95 1219/1

- The National Archives War Office: First World War Representative Medical Records of Servicemen MH106/955, MH106/1609 and MH106/1623 – extracts via Forces War Records

- Fryer, E. R. M. Reminiscences of a Grenadier: 1914-1919. London: Digby, Long & Co, 1921.

- Ponsonby, Frederick. The Grenadier Guards in the Great War of 1914-1918. London: Macmillan and, Limited, 1920.

- The Long, Long Trail – The British Army I’m the Great War 1914-1918: https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/