This is the story of an unsung Batley hero, living behind enemy lines and carrying out works of espionage and sabotage during World War One. His adopted pigeon Charles played an important part in the Yorkshireman’s wartime exploits. Their daring deeds read more like a boy’s adventure story than real life. But this is a true tale of wartime courage, and one which deserves wider telling.

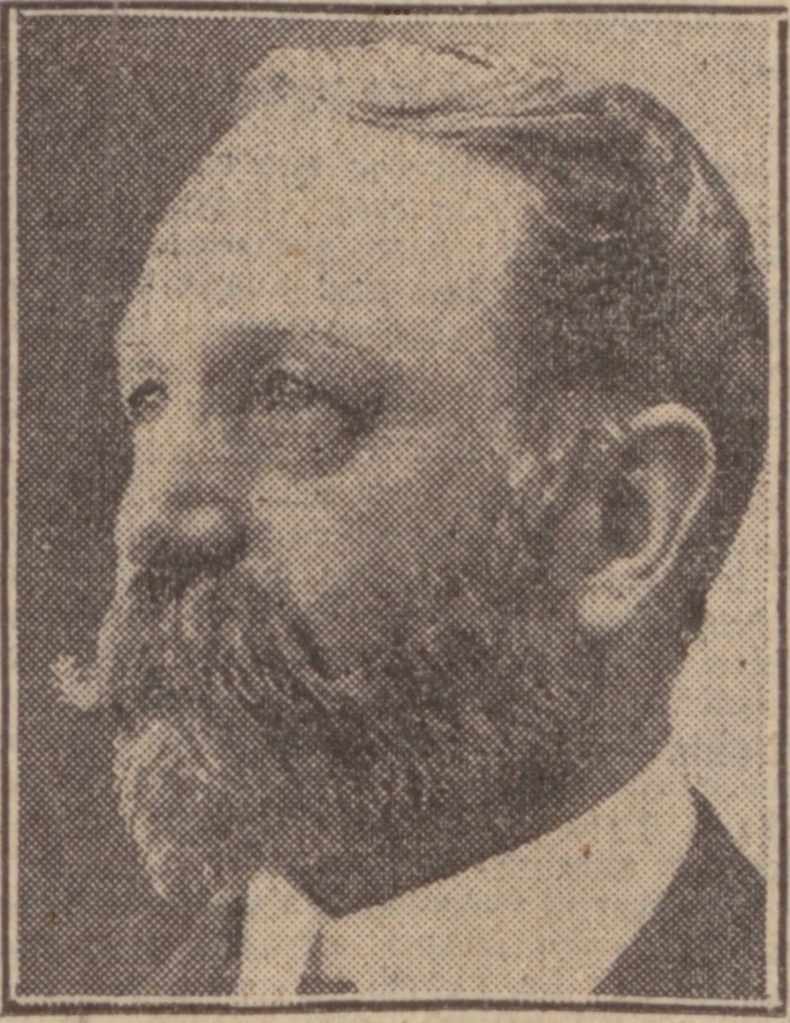

George William Richardson was born in Hunslet in 1859, and baptised at Thornhill parish church. His parents were Thornhill-born glass bottle maker Benjamin Richardson and Mary Peace, who married at Hunslet St Mary’s earlier that year. George was the eldest of their 15 children. The Richardson family were well-known in the Batley area, with George being the nephew of local dyer Edward Richardson.

George spent his early years in Liverpool where his father, Benjamin, worked. But by the mid-1870s Benjamin changed career and moved to Batley where he set up business as a grocer and provision dealer in the Mount Pleasant area. The family home was in Denison Street, Purlwell.

A keen young all-round sportsman, George played in the forwards for the Batley Mountaineers Rugby Football team. He also won trophies for long-distance running and walking. This included first prize of two bronze vases on marble pedestals for the two miles’ walk at the Dewsbury United Clerk’s Sports at Crown Flatt in July 1878; the following month a timepiece and a guinea for first in that distance at the Heckmondwike Football Club Athletic festival; and second place over the same distance in a controversial walk in the first Batley Hospital Sports festival, also in August 1878 – so controversial the event was dropped from the following year’s programme.1 One article reported that he also won the Yorkshire Roller Skating Championship.2

Described as a typical grim, bluff, wily Yorkshireman “quiet, dogged, and full of resource…”,3 he transferred the same perseverance and determination he applied to succeed in sport, to his working life.

It was in Batley that George began his grounding in various elements of the textile trade. His early job history included working in the cutting department at Messrs. G. and J. Stubley’s Bottoms Mill. He was also employed as a dyer at his uncle Edward’s Howley Bank dye works.

He left Batley in the early 1880s initially for Austria, and then on to France where he worked once more as a dyer, eventually saving enough money to buy the dyehouse in which he was employed.

In December 1886 he travelled from his then home in the French city of Tourcoing, on the border with Belgium, across to the British Legation (a Diplomatic Mission more common than Embassies in this period) in Brussels to marry Rebecca Willby.

By the early 20th century George’s business was flourishing. In 1906 he owned what was described as “probably the largest dyehouse in France”.4 His portfolio now also included a textile factory in Roubaix, a French town adjacent to Tourcoing, the town in which he and his family settled. He was living here in 1906 with his wife Rebecca, daughter Gertrude, and sons Alphonse, Frédéric and Georges.5

The G. W. Richardson and Co. factory in Roubaix was founded in 1898, and was initially known as Lemaire frères et Richardson. It manufactured fancy coatings and ladies’ cloths. By February 1906 it employed over 500 hands.6 This was the month George Richardson received the Chevalier du Merit Agricole, which the British press equated to a knighthood. When this honour was created in 1883, it was second only to the Legion of Honour in the French order of precedence.

As business grew, other specialities of the factory included renaissance carded wool fabric, pure wool fabric, drapery, dress and cap fabric, fabric for the railways, and military sheets, with trade including supplying governments.

George always retained his love and pride for Yorkshire, reminiscing about his days in “dear old Batley”,7 and even in the late 1920s declaring “I’m Yorkshire through and through”.8 Over 40 years after leaving the district, he was described as being “as Yorkshire to-day as ever” both in manner and speech.9 He remained in touch with his Batley friends, looking forward to coming over for a cup of tea with them, and he regularly visited his parents. Although his father died in 1912, his mother remained in Batley, living in a tiny one-roomed cottage in Chapel Fold, Staincliffe, until her death in 1926, despite George pressing her to move to a larger house.

Interestingly, though, in post-war reports – particularly in Leeds newspapers – his Batley links were not mentioned, the emphasis being Leeds (and some newspapers even said the Bradford district!) The Batley News were so indignant as to point out to its readers that he was a native of Batley, not Leeds as stated in several of the daily papers.10

He was visiting family in Batley in September 1914 during the first weeks of the war, whilst one of his sons was a student at Leeds University. Both rushed back to Roubaix, his son to join his two brothers who were about to enlist in the French army. All three boys ended up as prisoners of war at the notorious Wittenberg camp, but were eventually transferred to Ruhleben camp – possibly because a German officer, who had before the war done business with the Richardson’s Roubaix mill, recognised them.11 All three brothers survived the war.

In mid-October 1914, the German Army occupied Roubaix and remained there for the next four years. This marked the start of George’s exploits. As the Germans threatened to overrun Roubaix, he took the identity of a Belgian he closely resembled and changed his name to Dupont, though it appears this switch did not last long.

As an owner of a major mill, George refused to make cloth for German uniforms and was taken before the Commandant who threatened to shoot him if he did not start the machines. He coolly replied “Will you get your cloth if you shoot me?”12 The Commandant drew back from his threat. George was proud to say “Not one yard of cloth was made for the Germans all the time they held my mills”.13 For whenever the cloth-making process seemed likely to start, something would always mysteriously go wrong. As George recalled with a chuckle, “I diddled them every time.”14

His acts of sabotage commenced right from the early days of the war, as the Germans were approaching. He and his trusted foreman took all the vital parts out of the machines and buried them in a shed a mile away. The pair then replaced the key machinery parts with cracked ones, rendering the machines unusable.

The mill also had a tunnel and false wall behind which copper was tightly packed. As a result, he managed to conceal around £20,000 worth of the metal. Though there was one very lucky escape later on in the war, when a group of armed soldiers made a sudden mill inspection. They examined every nook and cranny, the officer in charge insisting on descending every stairway and probing every corner of the basement, the labyrinth details of which few beyond George knew. The officer became curious about one of the walls – the false one behind which the copper was hidden. But because it was so tightly packed, tapping it produced no suspicion of hollowness, meaning the copper was not discovered. They also bored into the floor, but missed the tunnel.

The Germans arrived before the task of incapacitating the mill and removing valuable materials was fully complete, so some items were carried out under the noses of the enemy. George and his trusted employee went to the mill almost daily under the pretence of trying to get the machinery working. They always came away with bits of lead, which they smuggled past the pair of fixed-bayoneted German soldiers. It is estimated George threw three tons of lead stealthily into the canal by this means. Several bicycles were dismantled and similarly disposed of. George also burned around six tons of sacking which the Germans would have used for sandbags.

Throughout the time his mills were commandeered by the occupiers, George continued to hide copper tubes, connections and joints, so cloth could not be woven. When the Germans planned to clothe some of their soldiers in khaki uniforms to mislead the Allies, George had the dyestuffs arranged so that every attempt at dying cloth the requisite shade ended in failure.

Other thrilling stories included the time when, disguised as an Italian, George saw a German soldier stealing potatoes from an old woman. He knocked the German down, and then saw other Germans were running towards him. He knelt down and began wiping the mud off the soldier’s face, and by the time the others arrived he was giving him brandy. Once the true story was discovered, that George was the assailant not a saviour, he was brought in by the Germans and given a public flogging.

The Batley News reported the Germans attempted to assassinate George. They reported he was struck on the neck with a dagger but, although scarred for life, he was spared.15 For another newspaper report George recalled:

A huge Prussian darted at me one dark night and put a knife in my neck. I bowled him over. He was a well-educated man, for he begged on his knees for mercy in German, French, and English. 16

When the Germans became suspicious of him, they sent him to Austria via a cattle truck. The journey took three days and four nights. He received such severe punishment at the hands of his captors that he decided to make them think their cruelty had affected his brain. The ruse succeeded and they returned him to Roubaix, believing him to be a “harmless lunatic”.17 There he maintained the pretence.

The Germans, believing he was “daft”18 and not realising he was a fluent German speaker, were careless with their talk in front of him. It meant he gleaned an astonishing amount of information from them, intelligence which was then passed onto the Allies, via his daughter Gertrude.

It also resulted in more narrow escapes. Once, while carrying a despatch, he was arrested, (one of around his six arrests during occupation). When the Germans were taking him away, he pretended to slip to the ground, and whilst he lay there he managed to swallow the two-inch square document. Stripped, even the soles of his feet were examined, nothing incriminating was found.

Some of George’s most dangerous exploits involved pigeons. A keen pigeon fancier before the war, Charles the pigeon was left in George’s care when his owner, Felix Vanoutryve, went off to join the French army. Charles was not any old pigeon. She (yes, Charles was a female) was a very special bird. Bred by Messrs. Bracey and Cooke at Martham, Great Yarmouth, the black magpie hen (hen being the term for a female pigeon) was exhibited at Crystal Palace where she won first and Challenge Cup, and was subsequently bought by Essex pigeon fancier Frank Warner (later Sir Frank Warner) for £100, believed to be a world-record price in 1912. Later, Bracey and Cooke bought some of Warner’s pigeons, and Charles once more returned to Martham, before then being sold to M. Vanoutryve and taken to Roubaix.19

Owning a pigeon was forbidden in German-occupied territory. If discovered, the owner could be shot. Yet despite the personal risk, George did not take the easy option and ring the pigeon’s neck. It led to a series of narrow escapes for the Richardson family as the bird was hidden during repeated raids by the German occupiers.

On one occasion during a German house raid, Mrs Richardson hid Charles in the wash copper (a tub for heating water to wash clothes). She poured boiling water over the clothes at the bird’s side, in order to trick the Germans.

On another occasion, when the Germans conducted a night house raid, George had just enough time to grab Charles, tie her wings and wrap her up in the bedclothes next to his wife before the Germans entered the room. As the raiding party stood on the threshold, he begged the officer in charge to make as little noise as possible as his wife was ill, possibly with typhus – a potentially fatal, infectious disease which could ravage troops. Unsurprisingly, the Germans left without conducting a search.

Another incident occurred when a German patrol visited George’s factory in search of a piece of machinery. He and the German officer went down to the basement where the officer appeared to notice Charles’ head sticking out of a basket. George asked the German into his office, and distracted him with a piece of tapestry showing old Heidelberg, and pressed him to join him in drinking his “last”20 bottle of champagne. The officer’s glass was filled and refilled, until he became a little “fuzzy.”21 He eventually left, smoking a cigar, and made no comment about the pigeon. But George was taking no chances. A small bantam hen was substituted for Charles in the basket, and Charles was hidden elsewhere. It proved a wise move. Shortly after, the officer returned, accompanied by two German soldiers with fixed bayonets, and a gendarme. The whole party went into the cellar, where the gendarme seized the basket, looked at the bird, and then pointed out to the officer it was not a pigeon, it was a bantam hen. Fooled by the switch, they left in disgust.

On another occasion, Charles could not be found when a German sergeant went to the Richardson house to billet an officer. George said the only accommodation was on the second floor but, with his foot on the stairs, the sergeant said German officers never slept on the second floor. The sergeant left, and when George went upstairs, he found Charles strutting along the second floor landing - the floor the sergeant had refused to look at.

George was amongst the prominent Roubaix residents imprisoned at Güstrow Prisoner of War camp, northern Germany, held hostage because the municipality refused to pay a £6,000 fine imposed by Germany. Whilst there, a friend in Belgium looked after Charles.

As soon as George was released, he retrieved the bird, and carried her in his pocket over the German sentry-guarded border, back into France. Fortunately, Charles was accustomed to being stashed in pockets. Her usual hiding place was nestling in George’s coat pocket, with string over her wings. Several times on the journey back, George had to hide in ditches, and then make a dash for it. He estimated at least a dozen shots were fired at him, and later he found a bullet had passed through his hat. The hat, along with Charles, were exhibited at Crystal Palace in 1921.

When M. Vanoutryve returned to collect Charles after the war ended, and found out about the dangers involved in keeping her, he grasped George by the hand and said, “You damned fool!”22

His escapades with Charles were not his only involvement with pigeons. A local baker brought him a pigeon dropped in by the British, who requested they collect information about enemy regiments and send it back to them via the bird. Despite knowing if caught he would be instantly shot, George obtained the information, tied it to the pigeon and released it early in the morning, even though Germans were billeted in his house.

Life was a grim struggle in occupied Roubaix, food was scarce, and people died of starvation. But the Richardsons were amongst the more fortunate, having money. After being without meat for three months, George was able to pay 12s. a pound for the flesh of a horse which had been killed by a shell.

Through all the hardships and tribulations, the Richardsons, and their other compatriots from England, clung together and talked of days of freedom and celebrations to come, when their treasured bottles of wine would be brought out from hiding places. After his release from Güstrow, on his return to Roubaix George secretly built an underground storage area in which to stash his valuables from the enemy.

Towards the end of the war, British military prisoners were brought in once more and put to work in Roubaix, on heavy, manual tasks like loading stones at the canal and railway station. Some British prisoners were housed in the Richardson’s idle, ransacked and now dilapidated factory. Insufficiently clothed and fed, George and daughter Gertrude were amongst those who sneaked food to them, keeping them alive. They also managed to get fresh shirts and socks to them, prior to the prisoners being taken away from Roubaix in the autumn of 1918 by their retreating German captors.

When George once again entered his half-dismantled Roubaix mill in October 1918, he found it in a dilapidated state, with windows shattered, ironwork rusted and yards full of refuse left by the retreating Germans. As the war drew to a close in 1918, and German defeat was inevitable, they had removed over £250,000 worth of machinery from the mill, stripped copper from the boilers, removed dynamos from machines they did not take, even removed pieces of leather from the wire rods in the weaving rooms. They then smashed what remained. Around 150 packing cases of equipment ready for shipping to Germany lay abandoned, including spinning frames and boxes of paper tubes, ready to pulp. But once again George was able to place a tiny home-made Union Jack over the entrance of his mill, and another over the door of his home. The family spent all night making Union Jacks with which to welcome the British troops.

As soon as the Germans went, Gertrude wrote to her grandmother in Staincliffe:

We can hardly believe it is true that the Germans have left. It is so lovely to see the British Tommies walking through the streets. We are all still too excited to give you further details. We expect to come to Yorkshire for Christmas.23

Gertrude was a war heroine in her own right. Long before the outbreak of hostilities, she joined the Roubaix Red Cross undertaking charity work with them, and promising to serve with them in the event of war. On its declaration she was ordered to stay in Roubaix to treat the wounded on No 1 Ward in the St Louis Hospital.24 She was caring for the French and British wounded after the first Battle of Ypres in 1914, when the Germans entered the town in mid-October 1914. She continued nursing at the hospital whilst it was under German authority. Until mid-1915 this included tending to Allied prisoners interred in the Roubaix area. After this date, these Allied captives were either sent to Germany to be held as prisoners, or sent home in prisoner exchanges. Gertrude then nursed the local population, whilst undertaking more dangerous work, such as passing on intelligence to the Allies, including that gathered by her father – a job described as being of immense military value. And later in the war, time and time again, she secretly and fearlessly carried food and clothing to British prisoners who were once more back in Roubaix, including to those lodged in her father’s cloth mill. Just before the Armistice, with the Germans gone from Roubaix, she was asked to be an interpreter-nurse for the British Army, which she did for five months.

She, her father, and another war heroine, (Marie) Léonie Vanhoutte, were invited to England as guests of honour of the United Associations of Great Britain and France in November 1927. Born in Roubaix, Marie Léonie Vanhoutte, also known by the pseudonym Charlotte Lameron, initially trained as a Red Cross nurse, but then – when she could not countenance treating German occupiers – she became a French Resistance fighter and secret agent operating on the French/Belgium border. She was at one point in prison with the later-executed nurse Edith Cavell. Léonie, too, was sentenced to death by the Germans, but this was commuted to 15 years imprisonment. Gertrude and Léonie became known as “the Heroines of Roubaix.” On the visit to England, Gertrude placed a wreath on the tomb of the unknown soldier at Westminster Abbey, whilst Mlle. Vanhoutte laid a wreath at the foot of Nurse Cavell’s monument.

To commemorate the exploits of Charles, George was presented with a pair of alabaster pigeons at the dinner which formed a key part of the visit. This event was hosted by Lord Derby at the Rembrandt Hotel in London.

The list of honours and decorations bestowed on George by the French and Belgian governments show the high regard in which he was held. According to the Batley News, these included Knight of the Order of Legion of Honour; Knight of the Order of Leopold; Knight of the Crown of Belgium; Knight of the Order of Nassau, with Military Cross Grand Duchy of Luxembourg; Officer of the French Academy; Officer of the Order of Nicham Iftikar of Tunis; Order of the National Merit with Military Medal. He was also a member of the Northern France Delegate for the British Chamber of Commerce; Textile Expert for Law Courts; and Textile Expert for the Ministry of Commerce.25

Charles the pigeon died in March 1928. It was said after her death she was to be stuffed and preserved in the War Museum, Paris.

In his later years, George lived just outside Roubaix, in the town of Croix. This is where his wife, Rebecca, died in the early hours of 16 March 1922, at their 22, Rue de Roubaix home. George attributed his wife’s death to the war. Just over seven years later, at 8 o’clock in the morning of 18 March 1929, George died in the same house.

I uncovered the story of George William Richardson whilst undertaking research for a client into the wider Richardson family. I am sharing this research with their permission, supplemented by some follow-up work I have since undertaken.

If you would like me to research your family history, take a look at my research services and fees here. And note, as a special offer until 31 January only my hourly fee is reduced, as outlined here.

Postscript:

I want to say a big thank you for the donations already received to keep this website going. They really do help.

The website has always been free to use, and I want to continue this policy in the future. However, it does cost me money to operate – from undertaking the research to website hosting costs. In the current difficult economic climate I do have to regularly consider if I can afford to continue running it as a free resource.

If you have enjoyed reading the various pieces, and would like to make a donation towards keeping the website up and running in its current open access format, it would be very much appreciated.

Please click 👉🏻here👈🏻 to be taken to the PayPal donation link. By making a donation you will be helping to keep the website online and freely available for all.

Thank you.

Footnotes:

1. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 2 August 1879.

2. Batley News, 23 February 1906.

3. Leeds Mercury, 27 March 1928.

4. Batley News, 23 February 1906.

5. Spellings as per the France, Nord, Recensement, 1906.

6. Most reports said over 500 hands, but the Batley News of 16 February 1906 said over 600.

7. Batley News, 16 February 1906.

8. Leeds Mercury, 25 November 1927.

9. Leeds Mercury, 27 March 1928

10. Batley News, 3 December 1927.

11. Batley News, 26 October 1918.

12. Leeds Mercury, 27 March 1928.

13. Leeds Mercury, 26 November 1927.

14. Observer (Adelaide, S.A.), 14 January 1928.

15. Batley News, 26 November 1927.

16. Observer (Adelaide, S.A.), 14 January 1928.

17. Leeds Mercury, 26 November 1927.

18. Sheffield Independent, 26 November 1927.

19. There are some contradictions around the purchase of Charles, with some reports saying M. Vanoutryve bought him from Sir Frank Warner for £100. The version I have used is the one from The London Daily Chronicle of 21 February 1927, as recounted by her breeders Bracey and Cooke.

20. London Daily Chronicle, 17 February 1927.

21. Ibid.

22. London Daily Chronicle, 17 February 1927.

23. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 25 October 1918.

24. Batley News, 26 November 1927.

25.. Batley News, 23 March 1929.

Other Sources:

- Architecture et monuments, Usine G. W. Richardson et Cie, http://canalderoubaix.bn-r.fr/acc/img_carte7_1.html

- Archives départementales du Nord, registres d’état civil du Nord, Croix/D 1921 – 1924 and Croix/D 1929 – 1932.

- Censuses, England and Wales, various.

- GRO Birth, Marriage and Death Indexes.

- GRO Foreign Registers and Returns.

- Le Monde Illustré, 5 March 1923.

- L’usine Richardson, https://www.bn-r.fr/espace-thematique/le-textile-prend-l-eau-quand-le-canal-alimentait-les-usines/des-entreprises-textiles-proches-du-canal-1/l-usine-richardson

- Newspapers – including Batley News, 18 May 1912, 19 January 1918, 26 October 1918, 30 October 1926; Batley Reporter and Guardian, 13 July 1878, 31 August 1878; Coventry Evening Telegraph, 8 March 1928; Dewsbury Reporter, 24 August 1878; Halifax Courier, 2 November 1927; Jedburgh Gazette, 29 November 1912; Leeds Mercury – 25 March 1929; London Daily Chronicle, 21 February 1926; North Mail and Newcastle Chronicle, 26 November 1927; The Sphere, London, 10 December 1927; Yorkshire Evening Post, 25 November 1927, 8 March 1928; Yorkshire Post, 28 November 1927, 22 March 1929. This is not an exhaustive list.

- Parish Registers, England – various.