In “Shrapnel and Shelletta” [1] I wrote about war-associated baby names. This is a more seasonal post about a particular Christmas-associated family name.

When naming a baby at Christmas-time, which names conjure up this magical time of year? Which can be considered as festive and beautiful as this special period? Holly, Ivy, Joy, Noel/le, Merry, Nick or Rudolph might spring to mind. Perhaps Caspar, Gabriel, Emmanuel, Balthasar and Gloria? Or maybe the Holy Family names of Jesus, Mary and Joseph?

In contrast, which name would make you recoil with shock and horror? Which name would you think “No way! How inappropriate! What on earth are they thinking of?”

Probably near the top of the list would be the one associated with my family tree. For on 24 December 1826 at Kirkheaton’s St John the Baptist Parish Church (oh, the irony of date and church name)[2] the baptism of Herod Jennings took place.

Magi before Herod the Great, Wikimedia Creative Commons License, G Freihalter

Herod’s siblings included the equally wonderfully named Israel (baptised 20 June 1824) and Lot (born 8 March 1830), so some fabulous biblical associations there too. The other family names of James (baptised 24 September 1820) and Ann (baptised 20 October 1822, buried 7 July 1823) seem disappointingly ordinary in comparison.

Sarah died in 1832, age 36 leaving George to bring up his four surviving children. James married Sarah Pickles on 25 December 1839, another example of Christmastime events in this branch of the Jennings family![3]So, by the time of the 1841 census, it was just George and his two sons, Israel and Herod, along with a female servant Jemima Gibson living in the Upper Moor, Hopton household. Youngest child Lot was along the road at Jack Royd, with the Peace family. This may have been a permanent arrangement given the family situation.

By the time of this census young Herod already worked down the mine, a job which ultimately would possibly contribute to his death.

On 7 October 1850 he married Ann Hallas at St Mary’s, Mirfield. Both Herod and Ann lived at Woods Row, Hopton. Ann was slightly older than Herod, being born in 1824. By the time of their wedding, she was already the unmarried mother of two. Her son, Henry, was born in 1843; and my 2x great grandmother Elizabeth’s birth occurred in November 1850, 11 months prior to Ann’s marriage to Herod.

This then is my family connection to Herod: His marriage to my 3x great grandmother. And it is one of the mysteries I still hope the DNA testing of mum and me will solve. Was Herod the father of Elizabeth? She was certainly brought up to think so, with all the censuses prior to her marriage recording her surname as Jennings, whereas her brother Henry went under his correct Hallas surname. And when registering the birth of her son Jonathan, there is a slip when Elizabeth starts entering her maiden name as “Jen”. This is subsequently scored through and correctly written as “Hallas”.

It appears Henry too was minded to look upon Herod as his father-figure. At his baptism at St Peter’s, Hartshead in June 1857 he appears in the register as Henry Jennings, not Hallas. When he married Hannah Hainsworth at Leeds All Saints on 24 December 1866, his marriage certificate records his father’s name as “Herod Hallas”. And in 1870 he named his eldest son Herod. Although by no means a common name, a glance at the GRO indexes shows it did appear occasionally, along with its alternative forms of Herodius and the feminine Herodia. The fact Henry gave his son this unusual name seems to indicate a measure of affection for the man who brought him up. Finally, at the time of the 1871 census Herod, son William and nephew Charles were boarding in the Leeds home of Henry.

So, whether or not there is a DNA link, he is still a major figure in my family tree. And for me this brings home the fact that there is more to family, and family history research, than DNA links alone!

Herod and Ann had nine other children: Ellen (born April 1851), Louisa (born January 1853), Harriet (born November 1854), Mary (born May 1858), William (born 1860), Eliza (born April 1862), Rose (born 1864), Violet (born 1866) and James (born 1871).

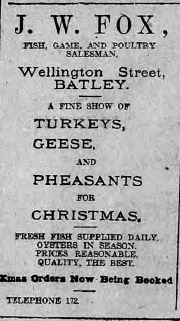

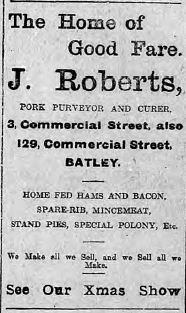

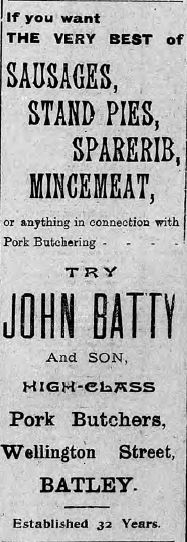

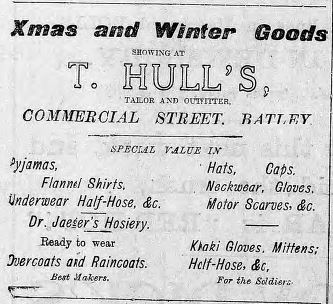

The family moved frequently, presumably due to Herod’s work as a coal miner. They are recorded at various locations in the area, many within walking distance of where I live. These included Mirfield, Battyeford, Hopton, Hartshead, Roberttown, White Lee and Batley.

Outside of work Herod had a keen interest in quoits, arranging and taking part in park challenge games especially around local Feast times. This game was particularly popular with miners and mining communities in Victorian times, with the metal rings being made of waste metal from mine forges. Challenge matches were also a way to raise funds, for example for sick and injured miners.

Herod died age 52, at Cross Bank, Batley as a result of asthma and bronchitis, which presumably owed something to his mining occupation. Working in cramped, filthy, air-polluted, damp, sometimes wet conditions from an early age, this was a hazardous and unhealthy occupation. The conditions and physical exertion led to chronic muscular-skeletal problems and back pain as well as rheumatism and joint inflammation. Most colliers had lung associated problems, with many becoming asthmatic whilst still relatively young. So Herod’s cause of death, from a lung-related illness, is unsurprising.

Ironically Herod’s date of death occurred on 5 January 1878, a day we associate with the Christmas period, falling before 12th night. And in the Western Christian tradition the 6 January is the Epiphany, marking the visit of the Magi to the infant Jesus in Bethlehem. This brings us once more to the King Herod connection, at Herod Jennings’ death as well as his baptism.

This is what Matthew’s gospel says about those events at the first Christmas:

“Then Herod summoned the wise men to see him privately. He asked them the exact date on which the star had appeared, and sent them to Bethlehem. ‘Go find out all about the child,’ he said ‘and when you have found him, let me know, so that I too may go and do him homage.’ Having listened to what the king had to say, they set out. And there in front of them was the star they had seen rising; it went forward and halted over the place where the child was. The sight of the star filled them with delight, and going into the house they saw the child with his mother Mary, and falling to their knees they did him homage. Then, opening their treasures, they offered him gifts of gold and frankincense and myrrh. But they were warned in a dream not to go back to Herod, and returned to their own country by a different way.

After they had left, the Angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, ‘Get up, take the child and his mother with you, and escape into Egypt, and stay there until I tell you, because Herod intends to search for the child and do away with him.’ So Joseph got up and, taking the child and his mother with him, left that night for Egypt, where he stayed until the death of Herod……Herod was furious when he realised he had been outwitted by the wise men, and in Bethlehem and its surrounding district he had all the male children killed who were two years old or under, reckoning by the date he had been careful to ask the wise men”.[4]

Herod was buried in Batley Cemetery on 7 January 1878.

I have a great deal of affection for Herod, whether or not there is a direct family blood-tie. The fact he took on one, possibly two children when he married Ann; and they in turn acknowledged him as a father, which speaks volumes for him. I can relate to the location links. And I can totally sympathise with his asthma suffering.

This is my final family history blog post of 2015, and an apt one given the time of year. Thanks ever so much for reading them. As someone new to blogging your support, encouragement and feedback has meant so much over the past eight months.

Merry Christmas everyone – wishing you all peace, health and happiness for 2016!

Sources:

- England Census 1841-1871

- GRO BMD certificates

- Newspapers – “Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer” – 1 August 1868

- Parish Registers – Batley, Hartshead, Kirkheaton, Leeds and Mirfield Parish Churches

- Photo, Stained Glass Window at Saint-Sulpice-de-Favières, by G Freihalter, Wikimedia Creative Commons License: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ASaint-Sulpice-de-Favi%C3%A8res_vitrail1_837.JPG

- St Matthew’s Gospel

- Traditional games: http://www.tradgames.org.uk/games/Quoits.htm

[1] Shrapnel and Shelletta: Baby Names and their Links to War, Remembrance and Commemoration | PastToPresentGenealogy https://pasttopresentgenealogy.wordpress.com/2015/11/04/shrapnel-and-shelletta-baby-names-and-their-links-to-war-remembrance-and-commemoration/

[2] Herod the Great was responsible for trying to elicit the three wise men to reveal the whereabouts of Jesus and, when this failed, subsequently ordering the killing of all infant boys under the age two and under, the so-called “Massacre of the Innocents”. His son, Herod Antipas, had John the Baptist killed.

[3] It was not uncommon for working-class people to have wedding ceremonies on Christmas Day. It was, after all, a holiday so they had time off work.

[4] The Jerusalem Bible, Popular Edition 1974 – Matthew 2: 7-17