At the beginning of October 1918, whilst lying paralysed and almost speechless in the Leeds Workhouse Infirmary, septuagenarian Ferdinand Hanson1 made international headlines.

This admittance to hospital brought a sensational, and very public, end to Ferdinand’s 30-year-old secret – it revealed the Hamburg-born widower, who claimed to be a Danish national, was actually a woman.

The secret began to unravel in early September 1918 on his customary weekly shopping trip to buy coffee from a shop on Boar Lane, Leeds. Returning home via Briggate, Ferdinand collapsed, suffering a stroke. Two women managed to get him back to his Leeds lodging house at Lilac Grove, just off Skinner Lane.

There, sitting by the fireside, Ferdinand’s condition worsened – but he stubbornly refused to let his landlady help get him into more comfortable clothing. He deteriorated so much that in the end she called the doctor, who advised admittance to hospital. Despite Ferdinand’s vehement protests, an ambulance was called.

Once in Beckett Street Infirmary, the reasons for Ferdinand’s protests became clear – undressed, it was discovered he was a woman. The Infirmary recorded their new patient under the name of Dora Hanson.

Ferdinand’s landlady of seven years, widow Carrie Green, collapsed in shock when told her male lodger was actually a woman. She could not conceive that the person with whom she shared her home for so long was anything other than a man. Perhaps there was also the dawning realisation that she may have been scammed out of hundreds of pounds.

She had implicitly believed the back-story Ferdinand told her about his life. So much so that when the authorities investigated Ferdinand during the war and concluded he was German, not Danish, she managed to keep him out of an internment camp by promising to “look after the old man”.

Carrie described Ferdinand as exceedingly polite, never failing to raise his hat to the women in the neighbourhood. Short in stature, with a pale, rather finely-featured face, and with white, close-cropped hair, Ferdinand seemed well-educated, being fluent in seven languages. He gave the impression that a previous employer of 20 years was the White Star Line, for whom he acted as an onboard interpreter.

Ferdinand’s one vice was being a heavy smoker, using really strong and noxious smelling tobacco in his clay pipe. He even smoked in bed. Initially, Carrie objected, concerned he might inadvertently set the house alight, but her lodger assured her “it is all right; I have always been very careful”. After the sex revelation, some theorised this excessive smoking was adopted as a means to reinforce Ferdinand’s masculinity – although, to be fair, many women did smoke pipes.

Ferdinand also claimed to have travelled extensively in the United States as an expert photographer, working in several cities – including Philadelphia, Washington and New York. It was in the latter he said he married, his wife working as a milliner in that city.

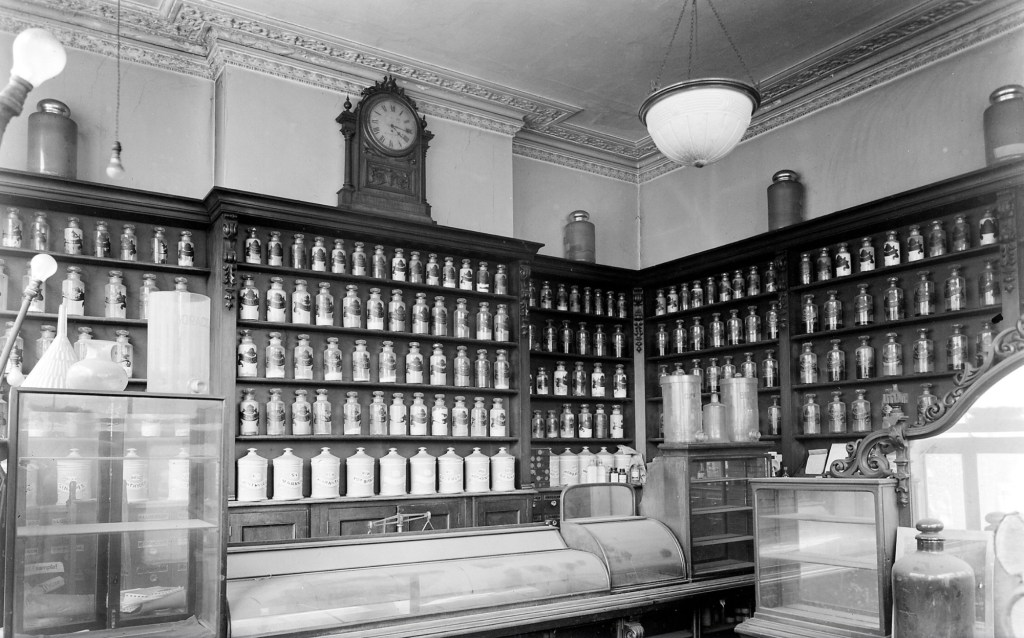

He asserted it was the death of his wife which prompted his return to Europe, with him settling in Yorkshire where he obtained work in various photographic shops as a photographer-canvasser. This was an advertising role, promoting the studio employing him. Initially he lived in Dewsbury, working for a photographer there. After his move to Leeds, he worked in a Grand Arcade photographers shop, though he had been unemployed in the years leading up to his seizure.

Ferdinand Hanson took up lodgings with Carrie Green in around 1911, having previously boarded for around 12-14 years with Batley Carr-born Martha Whitaker. The suggestion was he first stayed with Martha when she ran digs in Dewsbury. By 1901 she and her husband William ran a boarding house on Wade Lane, Leeds. Martha then moved to Portland Crescent in Leeds, where she continued as a boarding house keeper after her husband’s death. Unfortunately, Ferdinand is not recorded in the 1901 and 1911 censuses with Martha, either at Wade Lane or Portland Crescent. A canvasser’s job did involve travelling though.

It was Martha who recommended Ferdinand to Carrie, as a “quiet, respectable, well-behaved gentleman”. Martha was dead by autumn 1918 when Ferdinand’s secret came to light. It was left to Carrie Green and Martha’s adopted daughter, the now married Dorothy Emms,2 to wrack their brains for any missed clues.

Dorothy, who was only a child when Ferdinand stayed with them, remembered his lack of friends, and his frequent solo rambles through the streets of Leeds. He also used to receive regular letters from abroad which Dorothy believed contained money. These letters stopped by the time Ferdinand lodged with Carrie, who could only think of one letter ever arriving for him.

Though Ferdinand was adept at needlework, Carrie believed the explanation given to her – being married to a milliner, he used to help his wife trim hats. According to Carrie, Ferdinand was very domestically inclined, washing all his own clothes, helping out around the house, and he even rather liked peeling potatoes! She interpreted this as Ferdinand being anxious to lighten her load.

There was only one possible clue that all might not be as seemed, with Dorothy recalling occasional comments about the remarkable whiteness and softness of Mr. Hanson’s skin.

There was, however, a much darker side to this tale. Because Ferdinand never paid Carrie as much as a solitary sixpence in the entire seven years he stayed with her. In fact, she even lent him money to buy clothes. In effect, Ferdinand conned her, under the pretext of having a wealthy sister living in Hamburg who had willed all her possessions to him. He told Carrie, as he had no other relations in the world, he would share his entire inheritance with her. Carrie believed him. It was an expensive error of judgement. She calculated the scam left her £300 out of pocket. It also destroyed her trust in people.

Some speculated that work was the reason Ferdinand lived as a man for 30 years – it helped secure photography jobs. But despite attempts to find out the motive directly from the horses mouth, it was a secret which Ferdinand took to the grave.

Never recovering from that life-changing stroke, almost two years later 74-year-old Ferdinand Hanson died in the Leeds Workhouse Infirmary. And although the hospital did give Ferdinand a female name on admission, Ferdinand was the name under which the death was registered, and the name recorded in the Harehills Cemetery burial register when the enigmatic Ferdinand Hanson was laid to rest on 25 May 1920.

Postscript:

I may not be able to thank you personally because of your contact detail confidentiality, but I do want to say how much I appreciate the donations already received to keep this website going. They really and truly do help. Thank you.

The website has always been free to use, and I want to continue this policy in the future. However, it does cost me money to operate – from undertaking the research to website hosting costs. In the current difficult economic climate I do have to regularly consider if I can afford to continue running it as a free resource.

If you have enjoyed reading the various pieces, and would like to make a donation towards keeping the website up and running in its current open access format, it would be very much appreciated.

Please click 👉🏻here👈🏻 to be taken to the PayPal donation link. By making a donation you will be helping to keep the website online and freely available for all.

Thank you.

As a professionally qualified genealogist, if you would like me to undertake any family, local or house history research for you do please get in touch.

More information can be found on my research services page.

Footnotes:

1. Hansen was another surname spelling variant. I have used Hanson in this piece as this was the name used for death registration.

2. Dorothy Whitaker was born in Scotland in 1895. Although she is recorded as Whitaker in the 1901 and 1911 censuses, her birth surname was Novello.

Other Sources:

• Censuses England and Wales, various dates.

• Harehills Cemetery Burial Register.

• GRO Indexes.

• Newspapers – Various.