Grade I Listed Oakwell Hall is a glorious Elizabethan-built former Manor House in the heart of West Yorkshire. Located in a 110-acre country park in Birstall, the building stands relatively unchanged since the 17th century. For this reason it is often used as a setting for period dramas ranging from Gunpowder and Gentleman Jack to Anne Boleyn and Wuthering Heights.

It has a fascinating, and sometimes quite macabre history, too. It includes outrageously scheming owners, an eccentric huntsman, English Civil War and Brontë links, capped off by the sudden deaths of the two men responsible for preventing its removal to America. And of course no self-respecting Elizabethan hall would be complete without a resident ghost.

In this blog post I’ll introduce you to some of these characters and tales.

In medieval times Oakwell was a small farming community, with its own fields grouped around the settlement. It is unimaginatively named Oakwell, because the surrounding oak woodland contained a well. Sources indicate a timber framed house stood there in 1310, with this then being replaced by a larger timber framed building. There is also evidence of a moat.

The Batt family is the one most associated with Oakwell Hall, with the manor being purchased from the Piggott family in the mid-1560s by Halifax-born Henry Batt. He was a well-connected and ruthlessly ambitious Elizabethan business man. Linked to the Waterhouse family of Shibden Hall through his marriage to Margaret Waterhouse, he also acted as a receiver of rents for another powerful local landowning family, the Saviles of Thornhill.

Through this network of connections, Henry amassed enough wealth to purchase not only Oakwell, but Heaton and Heckmondwike Manors too.1 But in clawing his way to the gentry classes, he was not averse to the occasional dastardly deeds to boost his income and influence.

Variously described as ‘unprincipled and avaracious’, ‘a sacrilegious vagabond’, and nicknamed ‘the dilapidator’, he stands charged with many underhand activities.

One particularly sordid, and complicated, crime he stands accused of is the Machiavellian role he played in a plot to seize the infant heiress of a Liversedge landholding family, the Rayners, following the sudden death of her father William in August 1550. He was puppet-master in the plot, playing off the two-month-old’s great-uncle Marmaduke Rayner against Sir John Neville of Liversedge Hall, in their respective schemes to make her their ward, and to gain control of the Rayner lands and wealth. He took bribes from both parties, and directed their actions. In the midst of it all, William Rayner’s widow lost her husband, child and home.

He is also reputed to have taken advantage of the religious turmoil of the time to steal the great bell from Birstall parish church, melting it down to benefit his coffers.

Another accusation levelled against him was tearing down the vicarage in Birstall churchyard, and making off with the stones.

He is also supposed to have appropriated for his own purposes a sum of money designated to provide schooling for poor children of Birstall. Perhaps the £5 annual support his great grandson John Batt was listed as giving in the 1640s for a free school in Birstall was partial reparation for this. It is a strong possibility for, after Henry’s death, an inquisition at Elland found him guilty of the crime and his heirs ordered to make amends by way of a fine and an annual endowment.

Henry’s son John Batt had an equally sordid reputation, described as a ‘base fellow’ because of his scurrilous deeds. In a tale of ‘like father, like son’ he stands accused of the destruction of a cottage in order to use the stones. Or was it more a case of the father and son tales being conflated? Because other sources claim it was John who continued where his father left off, blackening his name for ever, by shamelessly taking the hauled-down vicarage stones to build a house on his own land. Perhaps it was these stones which were partly used in the building of Oakwell Hall, erected for John Batt in 1583. That year is etched on the date stone, along with the initials JB. The building is said to incorporate some of the earlier wooden structure.

I will not describe Oakwell Hall as this is well-documented elsewhere, including by Historic England here, and the West Yorkshire Archive Service here. Substantial remodelling did take place even in the early years, but by the late 17th century this work petered out.

Oakwell Hall, main door by Stephen Craven with the initials and date inscribed. Perhaps a latter addition, as a much-eroded date appears to be originally inscribed in the stone beneath

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic

Following the death of John Batt in July 1607, the hall passed to his son Robert.2 A rector at Newton Tony in Wiltshire, he was an absentee Lord of the Manor, leasing out the hall to his Waterhouse relatives. He died in February 1617, leaving a young family. His eldest son and heir John was still a minor, being baptised at Newton Tony in 1606. He only took up his inheritance in 1631, age 25.

Arguably, under his tenure the hall reached its zenith. More remodelling of the hall took place, with the star of the show being an elaborate new ceiling in the Great Hall – a masterpiece sadly destroyed when a chimney came down in a storm in 1883.

The flamboyant new Lord of the Manor mingled easily with the gentry, the Batts now their equals rather than the new kids on the upper-class block.

But these were tumultuous times and, with the country descending into Civil War, John Batt tied his flag firmly to the Royalist mast, serving as a Captain in the regiment of his friend Sir William Savile of Thornhill Hall. The latest Batt Lord of the Manor was also accused of unprincipled behaviour. In 1642, he presented King Charles I with £100, which was said to be part of the wealth stolen by his great-grandfather Henry. John Batt’s allegiance to the cause of Charles I would ultimately come at a bigger price.

On 30 June 1643, the Civil War literally crossed the threshold of Oakwell Hall. That day, a mile away at Adwalton Moor, 4,000 Parliamentarians headed by Lord Fairfax and his son Sir Thomas Fairfax, clashed in a three-hour battle with a 10,000-strong Royalist force headed by the Earl of Newcastle. Suffering 500 casualties, the bloodied and defeated Parliamentarians fled the battlefield, passing down Warrens Lane (now Warren Lane), adjacent to Oakwell Hall, earning it the gruesome nickname ‘Bloody Lane’.

Knowing it to be a Royalist household, some Parliamentarian soldiers burst through the doors seeking revenge on Captain John Batt. Some reports of this event say an unnamed royalist soldier in the house evaded capture by secreting himself in a hidden cupboard in the gallery. Others claim John Batt was there, but escaped up a chimney. Others say he was absent. Whatever the circumstances, he was not caught. However, his terrified wife was at home. Having recently given birth, she was confined in the Hall with her nurse. The nurse’s fear was so great she fled to Pontefract with the baby, remaining there until safety was assured. For a while it was, with the victory at the Battle of Adwalton Moor securing the north for the Royalists for the remainder of 1643.

But the Royalists’ luck did not hold. In August 1644, John Batt had no choice but to render allegiance to Lord Fairfax, the Parliamentarian General of the North. With the Parliamentarians victorious, he was forced to pay a heavy financial penalty for his support of King Charles I. The gloriously named Committee for the Compounding With Delinquents imposed on him a fine of £364, a tenth of the value of his estate. The family never financially recovered.

John Batt, along with three of his sons, set sail for America in an attempt to recoup some of the family losses. It proved a failure. According to Dugdale’s Visitation to Yorkshire, John’s eldest son died whilst sailing home from Virginia. From the same source it appears John Batt perished in 1652.

His son William succeeded him at Oakwell Hall, but died in 1673, reportedly heavily in debt.

We now come to arguably the longest-known resident of Oakwell Hall, William’s son Captain William Batt. Baptised at Birstall St Peter’s on 11 January 1659, he is the famous Oakwell Hall ghost. No lesser person than Elizabeth Gaskell wrote about him in The Life of Charlotte Brontë, describing him as the ‘reprobate proprietor’. She said:

Captain Batt was believed to be far away; his family was at Oakwell; when in the dusk, one winter evening, he came stalking along the lane, and through the hall, and up the stairs, into his own room, where he vanished. He had been killed in a duel in London that very same afternoon of December 9th, 1684.3

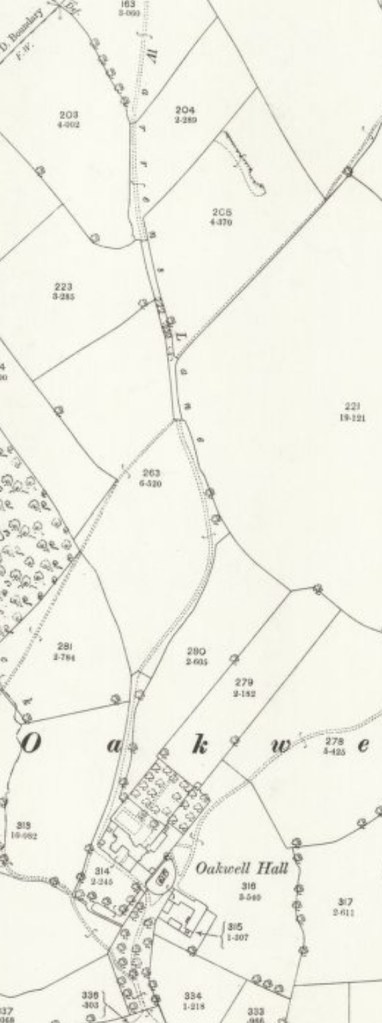

The lane Elizabeth Gaskell refers to is Battle of Adwalton Moor’s ‘Bloody Lane’, or Warrens Lane, and she asserted the walk was haunted by the ghost of Captain Batt. Note though that the route of this lane is not the same today, as the building of the railway line in 1900 resulted in it being diverted, as is illustrated in the two Ordnance Survey (OS) maps, below.

On the evening of 9 December 1684, his family, including widowed mother Elizabeth, were sitting by the fireside when William made his dramatic entrance. He never uttered a word to them as he walked through the Great Hall, past them, up the staircase, along the gallery, and to a chamber at the far end where he vanished. But they all recognised him. The only evidence he left of his presence was a bloody footprint in the bed chamber from where he vanished. The room in question is now known as the Painted Chamber. The macabre twist came when they realised what had happened to him that very day.

Snippets of the events were recorded by a local roving nonconformist minister and gossipy diarist, the Rev. Oliver Heywood. In his famous vellum book, which contained a register of various baptism, marriage and burial events, he noted in the burials section:

398 Mr Bat: in sport. 16844

Another publication of the Rev. Heywood’s varied documents has a further notation of the burial containing more details. No year is indicated but the entry is clearly referring to the death of William Batt:

Mr. Bat of Okewell a young man slain by Mr. Gream at Barne near London buried at Burstall Dec. 305

Other sources indicate the duel was the result of a debt, possibly related to gambling. Some say he had been in the Black Swan Inn, Holborn, that day, where he had borrowed money.

His body was brought home from London and his burial is recorded in the parish register of Birstall St Peter’s, taking place on 30 December 1684 – matching what was indicated in the Rev. Heywood’s notes.

In Victorian times, antiquarians, Brontë aficionados, and newspaper journalists seeking headline-making copy, visited the Hall and were regaled with the tale of the ghost of William Batt and his bloody footprint. It is said for decades after his death it was impossible to remove the stain, until a concoction of Hudson’s Soap or Brooke’s Monkey Brand did the trick.

Or did it? For even in the late 19th century the housekeeper was telling visitors it could still be seen…though she wouldn’t show it to them saying it was hidden underneath the carpet! And 20th century reports continued to circulate attesting to its existence, explaining it appeared and disappeared. One wag in the 1880s did say the footprint had nothing to do with Captain Batt and was more likely to be as a result of soldiers entering the Hall in the aftermath of the Battle of Adwalton Moor. Most Haunted filmed there in 2015 and said evidence of ghostly activity was present.

The last man to own the Hall with the Batt surname was John Batt, son of the William Batt who died in 1673. John died childless in 1707. The Hall was divided and went to distant relatives. In 1747 the bulk of the estate, including the Hall, was sold to solicitor Benjamin Fearnley.

Keen on blood sports, he perhaps is best remembered for the gravestone and epitaph he prepared for his huntsman Amos Street, well before the man’s death on 3 August 1777. Amos was buried in Birstall churchyard and the inscription, with its sting in the tale for the reader, went:

This is to the memory of Old Amos,

Who was when alive for hunting famous,

But now his chases are all o’er,

And here he’s earth’s of years four score,

Upon this stone he’s often sat,

And tryed to read his epitaph,

And thou who does so at this moment,

Shall ere long somewhere ly dormant.6

Fearnley borrowed heavily to purchase Oakwell Hall, and when he died his family were forced to sell it in 1789. From then on it was owned by a series of absentee landlords who rented it out. This, plus the financial difficulties of the last Batt owners, meant no substantial changes were made to Oakwell Hall from the mid-17th century, which is why it is such a wonderfully preserved example of a manor house from that period.

And it is in this absentee landlord phase that the event occurred which triggered the reason why the building is internationally famous today.

In the 19th century a series of tenants ran boarding schools for boys and girls. In the 1841 census, Hannah Cockhill and her daughters ran a girls’ school from the Hall. The Nussey family and the Cockhills were related, and Charlotte Brontë visited the school with her great friend Ellen. It clearly made a huge impression on her. In 1849 her second novel ‘Shirley’ was published. The novel’s Fieldhead, ancestral home of the eponymous orphaned heiress Shirley Keeldar, was based on Oakwell Hall. Charlotte described it in detail in the novel. One passage read:

If Fieldhead had few other merits as a building, it might at least be termed picturesque. Its regular architecture, and gray and mossy colouring communicated by time, gave it a just claim to this epithet. The old latticed windows, the stone porch, the walls, the roof, the chimney-stacks, were rich in crayon touches and sepia lights and shades. The trees behind were fine, bold, and spreading; the cedar on the lawn in front was grand; and the granite urns on the garden wall, the fretted arch of the gateway, were, for an artist, as the very desire of the eye.7

And elsewhere:

This was neither a grand nor a comfortable house; within as without it was antique, rambling, and incommodious.8

Elizabeth Gaskell in The Life of Charlotte Brontë, said of the Hall:

It stands in a rough-looking pasture-field, about a quarter of a mile from the high road. It is but that distance from the busy whirr of the steam-engines employed in the woollen mills of Birstall; and if you walk to it from Birstall Station about meal-time, you encounter strings of mill-hands, blue with woollen dye and cranching in hungry haste over the cinder-paths bordering the high road. Turning off from this to the right, you ascend through an old pasture-field, and enter a short by-road, called the “Bloody Lane” ….From the “Bloody Lane,” overshadowed by trees, you come into the rough-looking field in which Oakwell Hall is situated. It is known in the neighbourhood to be the place described as “Field Head,” Shirley’s residence. The enclosure in front, half court, half garden; the panelled hall, with the gallery opening into the bed-chambers running round; the barbarous peach-coloured drawing-room; the bright look-out through the garden-door upon the grassy lawns and terraces behind, where the soft-hued pigeons still love to coo and strut in the sun, — are all described in “Shirley.”9

The appearance of Oakwell Hall in a Brontë novel has subsequently acted as a magnet for Brontë aficionados worldwide.

Skip forward to the mid-1920’s for my final tale in my quick canter through the history of Oakwell Hall. Owned at this stage by absentee landlords Ray and Fitzroy Estates, rumours abounded that at best the interiors were about to be stripped by antiques dealers; or at worst the entire hall was on the verge of being dismantled, bricks, wooden interior panels the lot, and sold to covetous Americans, who would transport to the United States to be rebuilt there.

This resulted in a huge outcry and the launch of a public appeal to raise the money necessary to purchase Oakwell Hall to ensure it was saved for the nation. By September 1927, donations – much contributed from admirers of the Brontë sisters – amounted to around £800.10 But this well short of the £3,000 required to purchase it, even given the owners’ intimation that they would contribute £500 to the public subscription fund if the Hall was bought.

But £3,000 was the tip of the financial iceberg. Additional money would be required to put the building into a good state of repair, and then maintain it going forward. The campaign organisers were beginning to despair the money would be raised, especially given the difficult economic conditions.

But in September 1927, two Harrogate resident philanthropists, both leading figures in the wool trade, came to the rescue. Batley-born Sir Henry Norman Rae (better known as Sir Norman Rae), who was a former pupil at Batley Grammar School, and at one time Liberal MP for Shipley, joined forces with his friend, Halifax-born John Earl Sharman. They would be prepared to buy the Hall and save this important historical building with its famous literary links for the nation. Over the next few months a deal was thrashed out.

The deal saving the Hall from American relic seekers was announced on 3 January 1928, with the contract to be signed the following day. In an offer estimated to be worth between £4,000 to £5,000, Sir Norman Rae and John Sharman would purchase the Hall, put it into a proper state of repair, lay out the grounds, and provide suitable period furnishings for the interior, then hand it over to Birstall Urban District Council. In return, Birstall Urban District Council would act as custodians for the Hall which was to be maintained as a typical Yorkshire Manor House with domestic furniture illustrative of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries; allow reasonable public access; and see that the buildings and grounds were kept in good order going forward. The donations received to save the Hall was diverted to form part of the ongoing maintenance fund.

Some of the more unusual conditions attached to the deal included the forbidding of the sale or consumption of alcohol on the premises. Neither was private occupation of the Hall to be allowed, except by a caretaker. And, very wisely, the terms included a clause which stated the property could not be sold or mortgaged without permission from the Court.

But before 1928 ended, John Sharman and Sir Norman Rae would both be dead, in a matter of weeks of each other. In a strange coincidence, both had embarked on new romantic relationships.

On 8 November, at Marylebone Register Office, John Sharman married for a second time. His new bride was Miss Ada Burrows. Less than three weeks later, on 26 November 1928, he died honeymooning in Bournemouth.

Although not in the best of health and suffering from angina, Sir Norman Rae died suddenly on 31 December 1928. His death occurred whilst having tea at Westfield House (many older residents of Batley will remember it as the PDSA building on Healey Lane), the Batley home of his fiancée Elsie Taylor. The couple had only recently become engaged, his first wife having died in 1927. Elsie Taylor was a Batley Councillor, and the daughter of Joshua Taylor, one of the founding brothers of the renowned Batley textile firm of J., T., and J. Taylor. In 1932 she went on to become Batley’s first female Mayor.

Batley Council subsequently took over the running of Oakwell Hall. Now it is under the stewardship of Kirklees Council, who have the responsibility for preserving this unique piece of Yorkshire history for future generations.

I’ll conclude with the reason Sir Norman Rae put forward for stepping in to save the Hall. He asserted that the West Riding had not many such assets, and unless those that remained were cared for, the time would soon come when there was little or nothing worth preserving. Oh, that Kirklees Council, today’s custodians of many local Listed buildings, would take heed in respect not only Oakwell Hall but also their other Listed buildings in and around the Batley and Birstall area.

Postscript:

I want to say a big thank you for the donations already received to keep this website going. They really do help.

The website has always been free to use, and I want to continue this policy in the future. However, it does cost me money to operate – from undertaking the research to website hosting costs. In the current difficult economic climate I do have to regularly consider if I can afford to continue running it as a free resource.

If you have enjoyed reading the various pieces, and would like to make a donation towards keeping the website up and running in its current open access format, it would be very much appreciated.

Please click 👉🏻here👈🏻 to be taken to the PayPal donation link. By making a donation you will be helping to keep the website online and freely available for all.

Thank you.

Footnotes:

1. Some sources say Heckmondwike and Gomersal Manors.

2. I have based the Batt family tree on a number of sources including parish registers, probate records and Clay, J. W., Dugdale’s Visitation of Yorkshire, With Additions, Exeter: William Pollard & Co., 1893.

3. Gaskell, Elizabeth Cleghorn. The life of charlotte bronte:: … by E. C. Gaskell. Appleton, 1857.

4. Heywood, Oliver, and J. Horsfall Turner. The Rev. Oliver Heywood, B.A., 1630-1702, His AUTOBIOGRAPHY, Diaries, Anecdote and Event Books: Illustrating the General and Family History of Yorkshire and Lancashire. 2. Vol. 2. Brighouse England: A.B. Bayes, 1882.

5. Heywood, Oliver, Thomas Dickenson, and J. Horsfall Turner. The Nonconformist REGISTER, Of Baptisms, Marriages, and Deaths: 1644-1702, 1702-1752, Generally Known as the Northowram Or Coley Register, but Comprehending Numerous Notices of Puritans And Anti-Puritans in Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cheshire, London, &c., with Lists OF Popish RECUSANTS, QUAKERS, & C. Brighouse: J.S. Jowett, printer ‘News Office’, 1881.

5. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 08 July 1876.

7. Brontë, Charlotte. Shirley (Penguin Classics). Penguin, 2011.

8. Ibid.

9. Gaskell, Elizabeth Cleghorn. The life of charlotte bronte:: … by E. C. Gaskell. Appleton, 1857.

10. Amounts vary from £600 to £1,000 depending on source. £800 is the figure quoted The Batley News, 5 January 1929, when Sir Norman Rae died. However the same paper on 7 January 1928 said the fund stood at £704 0s 4d. when the Hall was saved on 3 January 1928

Other Sources:

I have used a raft of sources in compiling this blog post. Some of the information in these multiple sources is conflicting, with hard evidence lost in the mists of time. I’ve tried to make sense of the information and weave it into a coherent narrative, but in doing so I have had to rely heavily on the validity of the stories told about the dastardly deeds of the Batts. In addition to the sources in the Footnotes, I have listed the some of the others used below.

• Batley Reporter and Guardian, 01 May 1890, 10 October 1890, 30 July 1897, 21 February 1902, 21 June 1907

• Censuses, Various.

• Clay, John William. Yorkshire Royalist Composition Papers of the Proceedings of the Committee for the Compounding With Delinquents During the Commonwealth Volume II. Yorkshire Archaeological Society, 1895

• Country Life, 18 January 1990

• English Heritage Battlefield Report: Adwalton Moor 1643 https://historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/listing/battlefields/adwalton-moor/

• Haigh, Malcolm H. The History of Batley 1800-1974, 1978.

• Haigh, Malcolm. Batley Pride: More town tales. Batley: Malcolm H. Haigh, 2005.

• Halifax Evening Courier, 27 November 1928.

• Huddersfield Daily Examiner, 4 January 1928.

• Kirklees Council. “Oakwell Hall.” Oakwell Hall | Kirklees Council. Accessed August 11, 2024. https://www.kirklees.gov.uk/beta/museums-and-galleries/oakwell-hall.aspx

• Leeds Mercury, 28 September 1927, 15 October 1927, 04 January 1928.

• Oakwell’s Colourful Past Revealed https://www.bbc.co.uk/bradford/content/articles/2009/04/06/oakwell_hall_2009_feature.shtml

• Parish Registers, Various.

• Peel, Frank. Spen valley: Its past and present. Heckmondwike West Yorkshire: Senior and Co, 1893.

• Scatcherd, Norrison, The history of Morley, in the West Riding of Yorkshire; including a particular account of its old chapel. Morley: 1874.

• The Brighouse News, 27 July 1895

• The Battlefields Trust https://www.battlefieldstrust.com/resource-centre/civil-war/battleview.asp?BattleFieldId=4.

• Yorkshire Post, 04 January 1928, 9 November 1928.