The past few weeks have focused on those who served and lost their lives during the Battle of the Somme. But what about those closer to home whose efforts may have gone largely unnoticed?

In this blog post I’m turning my attention to another centenary. 21 July 2016 marks the 100th anniversary of the death of Barnbow munitions worker Ann (Annie) Leonard.

Annie Leonard

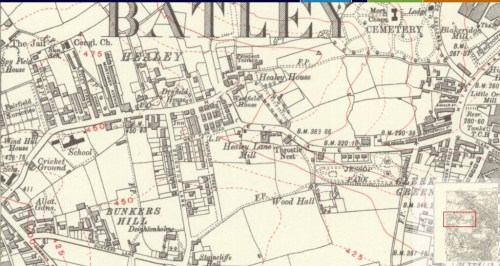

Annie was born in Morley in late 1891[1]. She was the eldest daughter of Leeds-born William and Emma Leonard (neé Dowd). The couple married in 1890 and, including Annie, they had 10 children. One child died in infancy but Annie’s other siblings included Edward (1894), Alice (1896), Walter (1897), Agnes (1900), Doris (1902), Ethel (1904), Elsie (1906) and Nellie (1908). All but Annie and Edward were baptised at St Mary’s RC Church, Batley.

In the 1891 census William and Emma lived at Springfield Lane, Morley. William was a coal miner. In 1901 the couple had five children and were still living at Morley, but their address had changed to New Park Street. William was now a coal miner deputy. This was the official employed in a supervisory capacity at the pit with responsibility for setting props and general safety matters.

By 1906 the family had moved to Batley and the 1911 census gives their address as North Bank Road, Cross Bank. This remained the family address when Annie died. At the time of this census William still worked as a coal miner deputy below ground. 19-year-old Annie, in common with many other local women, had employment in a woollen mill working as a cloth weaver.

War changed all this. Within weeks of its outbreak Annie’s eldest brother Edward, a former Batley Grammar School pupil with a talent for art, enlisted with the Leeds Rifles. He went to France in April 1915.

Around the time Edward went overseas the “shell scandal” debate raged at home, with the shortage of high explosives being cited as the reason for failure in battles and loss of soldiers’ lives. The war was lasting longer than anticipated; the number of men in military service was adversely affecting industrial and manufacturing output, including munitions manufacture; and the quantity of shells required was outstripping that of any other previous conflict. For example in the first 35 minutes of the March 1915 attack at Neuve Chappelle more shells were consumed than in the entire 2nd Boer War. There was a countrywide cry for “shells, and still more shells”.

The Government response was the 1915 Munitions of War Act with far-reaching Government powers in production. National Shell and National Projectile Factories were established, and National Filling Factories set up to fill these shell casings with explosives and attach fuses.

IWM Public Domain image by Edward F Skinner. See Wikimedia Commons footnote.

Interestingly, shortly after his arrival in France, Edward wrote a letter home to one of his sisters, possibly Annie. It is particularly noteworthy for his description of German shelling.

“Taking things all round, we have had a very quiet week as far as shells, etc, go. We had about the busiest day yesterday when the enemy started sending us shells and trench mortars over…..You can hear them whistle over, but cannot tell to a few hundred yards where they are going to burst. They “don’t half” make a row when they burst.

But the trench mortars are the worst. You can see them coming in the daytime. They look like bottles coming at about the speed a man throws a cricket ball. When they drop they are about 10 seconds before they burst; but when they do they shake everything for a good distance away. Personally, I think they are the most terrible things they send”.

Leeds had taken an initiative early in the war in setting up a shell production factory at the Leeds Forge Company, Armley. In August 1915 they took it a step further and oversaw the construction of the First National Shell Filling Factory at Barnbow, between Crossgates and Garforth.

Covering 313 acres at first, but eventually extending to 400, by December 1915 filling operations commenced with the employment initially of around 50 women. Operations were expanded with the Ministry of Munitons’ decision to install an Amatol filling factory at Barnbow in spring of 1916. Amatol was highly explosive, formed by mixing tri-nitro-tolene (TNT) and ammonium nitrate.

Barnbow was now responsible for filling and assembling QF artillery ammunition (13pdr, 18pdr and 4.5 inch), shrapnel and high explosive (HE). Output soon reached 6,000 shells a day.

Once the war ended and secrecy restrictions no longer applied, newspapers published the following statistics for Barnbow shell production:

- 12,000 tons of TNT were mixed with 26,350 tons of ammonium nitrate producing 38,350 tons of amatol;

- In the cartridge factory more than 61,000 tons of propellant (NCT and cordite) were made up into breech-loading cartridges, the highest record for one week being 938 tons. This material had to be carefully weighed on scales into ounces and drachms, giving an indication of labour intensivity and precision[2].

- Over 36 million breach loading cartridges were charged;

- Nearly 25 million shells were filled;

- Over 19 million shells were completed with fuses and packed into boxes;

- 566,000 tons of finished ammunition was dispatched overseas;

- If laid end to end the 18-pounder shells alone measured a distance of 3,200 miles, equivalent to the distance from London to New York

By October 1916 the workforce totalled around 16,000, although numbers subsequently declined to around 9,000. 93 per cent of employees were women and girls, with a woman/man ratio of roughly 16:1. About one third of the employees came from Leeds. Others were from Castleford, Normanton, Pontefract, Wakefield, Harrogate, Knaresborough, York, Selby, Tadcaster, Wetherby and surrounding areas.

In addition to railway lines for transporting raw materials and finished products, the North Eastern Railway Company operated 38 “Barnbow Specials” a day. These trains transported the workers to and from the site. There were also 15 ordinary trains. The workers had free work travel permits.

The Barnbow girls employed on shell-filling earned an average of around £3 a week. However, when the bonus scheme operated some girls could earn as much as £10-£12. Compare this to the wage of a domestic servant who earned as little as two shillings and six pence a week.

But the hours were long and the working conditions arduous, in part due to the nature of the explosive material the girls were working with. Nothing causing static and sparks was allowed: so rubber-soled shoes, smocks, caps only and no matches, cigarettes, combs or hairpins. Initially set up with two shifts a day, soon a three eight-hour round-the clock shift system came into operation. The girls normally worked six days a week with one in three Saturdays off. No holidays. No strikes.

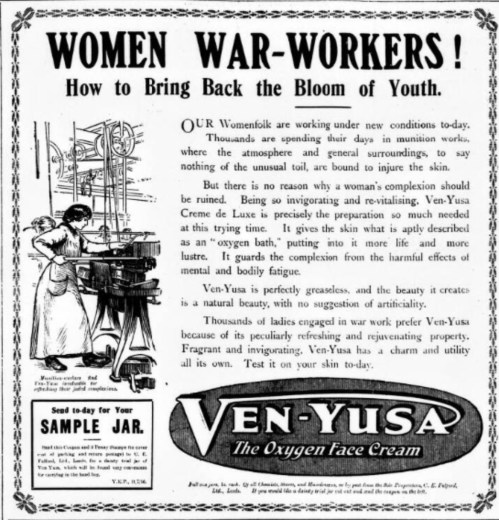

But above all the work was dangerous. Not for nothing was the pay high (but not the equivalent of a man!) There was the very real risk of explosion, three occurring at the Barnbow factory during the war. But more insidiously, the women worked with toxic material, and were at high risk of poisoning. The symptoms included nausea, vomiting, chest and abdominal pain, headaches, blurred vision, nose and throat problems. However the most obvious manifestation was the yellowing of the skin caused by toxic jaundice, earning the girls the nickname of “canaries”. Newspapers regularly advertised a skin product called Ven-Yusa aimed at preserving the complexion, and the “munitionettes” were a specific target-market for this product.

Ven-Yusa advert – The Yorkshire Evening Post, 11 July 1916

Milk was also thought to counteract the yellowness. So besides its three canteens, Barnbow had its own farm with crops and animals. Its 120 cattle produced 300 gallons of milk a day. The workers were allowed to drink as much milk and barley water as they wanted.

Despite the hard toil and dangers there was no shortage of women willing to apply for this work. Recruitment of such a large workforce over such a short space of time meant the opening of a new office at Wellesley Barracks, Leeds specifically for the task. One of the early employees Mrs Edith Haigh in an interview with the “Yorkshire Evening Post” in 1939 described her interview as follows:

“When I applied for work a woman interviewer asked me if my nerves were good, and told me to breathe deeply so that she could see how my lungs were. “Are you afraid of shells?” she asked. “I don’t suppose I shall be,” I said. “You are willing to undertake it?” “Yes, I’ll take it, whatever it is.”

It was this working environment Annie entered. As well as patriotic duty, perhaps her brother’s service and letter about shells had some influence.

With preparations for the Battle of the Somme, increased shell production was imperative. Annie was employed as a filler and stemmer at the factory. Explosive powder was poured, or “stemmed,” into the shell casings. A mallet and wooden drift was then used to compact the powder. Elsie McIntyre filled shells at Barnbow. She described the work as follows:

“We had to stem… when it first opened in the early part of the war, we had to stem the powder into shells with broom handles and mallets. You see, you’d have your shell and the broom handle, your tin of powder. And you’d put a bit in, stem it down, put a bit more in, stem it down. It took you all your time to get it all in. It was very hard work”.

Annie had not been working there long, but on 25 June 1916 she returned home complaining of sickness. Her face took on the typical yellow hue associated with munitions work. The family called in Doctor Fox. They also consulted a specialist. All to no avail. Annie’s condition worsened and she died on the morning of 21 July 1916.

Within hours of Annie’s death, her grieving family received more tragic news, with a wire informing them Edward had not been seen since heavy fighting on the 2 July. He was officially reported as missing.

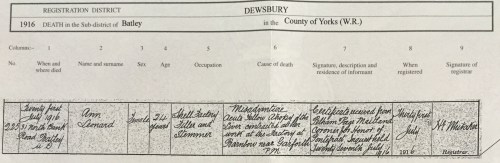

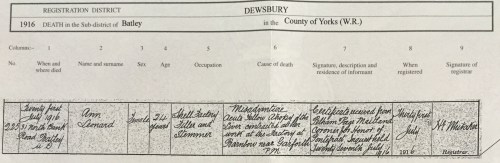

Annie’s inquest was heard behind closed doors on 27 July. Her death was recorded as “Misadventure. Acute yellow atrophy of the liver contracted at her work at the factory at Barnbow near Garforth”.

Annie Leonard’s Death Certificate

At this very difficult time for the Leonard family, with their daughter’s death and their deep anxiety about Edward’s fate, they still took the trouble to publicly thank people for their support, writing to the “Batley News“. Their letter was published on 29 July 1916 as follows:

“Mr and Mrs Leonard and family desire to take this opportunity to offer their deepest thanks, and express our most heartfelt gratitude to neighbours, friends and relations for their kindness and consideration, and most of all for the help and sympathy extended to us in this our hour of double trouble. We also send our thanks and sincere gratitude to the compatriots of our late daughter Annie working in the Barnbow Munition Factory, for the way in which they have shown their love for one who was only amongst them for such a brief time.

We earnestly desire our neighbours, who have shown such a love as is seldom found even in one’s own family, to accept these brief words of appreciation, in as much as it is impossible to express our deep feelings at such unassuming love, help and friendship shown by all. We therefore ask all to again accept our thanks.”

Besides being such a wonderful tribute to friends and neighbours, it highlights the support and camaraderie of Annie’s fellow Barnbow workers.

In late September 1916 the Leonard family received a further War Office communication. This updated the previous earlier information that Edward was missing. It was a bitter blow. He was now officially reported killed. Directly and indirectly the Battle of the Somme had claimed the lives of two of William and Emma’s children. Their eldest son fighting; their eldest daughter producing the shells required in the conflict.

The government was aware of the dangers of poisoning resulting from munitions work before Annie’s death, yet tried to play it down. They were keen to ensure an adequate labour supply to work in the munitions factories. In May 1916 the work was categorised a dangerous trade, but initially little happened in the way of regulations.

Investigations into the poisoning risks continued and in August 1916 “The Lancet” published the work of two female doctors, Drs Agnes Livingstone-Learmouth and Barbara Martin Cunningham. They were medical officers in munitions factories who studied the phenomena for a number of months. They produced a raft of recommendations including 21-40 age limits for TNT workers, provision of washing facilities, mandatory regular medical examinations, and moving workers elsewhere after 12 weeks. Following this, regulations were established with full-time doctors appointed to all large factories and part-time ones to the smaller operatives.

The topic of TNT poisoning also grabbed Parliamentary attention. In October 1916 Mr Anderson asked whether the Home Secretary was aware that of the 472 cases of industrial poisoning reported during the nine months to September 1916, 120 occurred from toxic jaundice, and that of the 62 deaths 33 were attributable to this cause. He asked how many of these were due to TNT poisoning. Mr Brace, Under-Secretary at the Home Office said of these 95 of poisoning cases were a result of TNT, and the number of deaths was 28. He went on to say “Every step is being taken by my department, in concert with the Ministry of Munitions, to investigate and deal with this disease.”

In November 1916 Mr Brace was again obliged to state that 41 workers in the UK had died in the six months to 31 October 1916 from either TNT poisoning or inhaling poisonous fumes.

But criticism of the measures taken to safeguard health continued. Echoing the cause of death verdict reached in Annie Leonard’s inquest, on 11 November 1916 Gertrude Ford in wrote in “The Daily Herald”:

“Since we last “observed” the world of women there has been another death from TNT poisoning; followed by another assurance from the Home Office that only some sort of “mistake” or “misadventure” was responsible. A properly administered Act, of course, leaves no loophole for “mistakes” that spell death to the workers affected by its operation. The accompanying assurance that everything will now be done to safeguard the health of the munitions-makers is an implied admission of the. If now, why not earlier?”

Yet even in December 1916 the Government was asserting the danger from TNT poisoning “seems to be much exaggerated in the popular mind”. However, the tighter regulations did begin to take effect and the death rates reduced. It is difficult to say with certainty the number of munition worker deaths attributable to poisoning. Some state as low as 109, while other estimates put it in the region of 400.

Annie is commemorated on the local Carlinghow memorial, at St John’s Church. She is one of 1,400 women whose names are inscribed on the oak screens of the National Women’s Memorial at York Minister. Her brother Edward, who has no known grave, is commemorated at Thiepval. There is a family burial plot at Batley cemetery, where both are remembered on the now broken headstone.

On 21 July I intend visiting the grave to pay my respects.

Annie and Edward Leonard’s Headstone in Batley Cemetery by Jane Roberts

A footnote to this story. Annie Leonard is not on the Batley War Memorial. Annie’s brother Walter did write to the Batley Town Clerk as follows:

Re. War Memorial

Dear Sir

With reference to the above I should like to draw your attention to the omittion [sic] of my sister’s name from the roll of honour.

She was the only Baltey [sic] girl who gave her life for her King & Country, and is on the roll of honour at Carlinghow St. John’s and Carlinghow Working Men’s Club, so I think it only fair to her and her folks that she should be placed amongst the Baltey [sic] Roll of honour.

She worked at the Barnbow Factory and was poisoned by T.N.T. poisoning.

Hoping this will meet your approval.

Yours Faithfully

W. Leonard

Her name ANNIE LEONARD

The letter was annotated with a large ‘No’.

Than omission has now been corrected. During the First World War centenary commemorations members of Batley History Group, who had undertaken research into those named on the War Memorial, identified Annie amongst those local people not remembered. As a result of their work their names, including Annie’s, were added to the Memorial in 2019.

Batley’s Roll of Honour website continues its work, remembering those on the Batley and Birstall War Memorials.

Sources:

[1] Birth registered in Q4 1891 Dewsbury 9b 580

[2] One-eighth of an ounce

GRO Picture Credit:

Extract from GRO death register entry for Annie Leonard: Image © Crown Copyright and posted in compliance with General Register Office copyright guidance

Batley Library – Photo by Jane Roberts

Batley Library – Photo by Jane Roberts

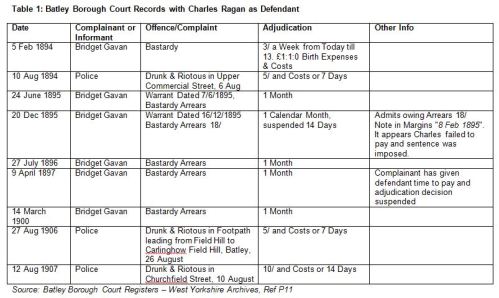

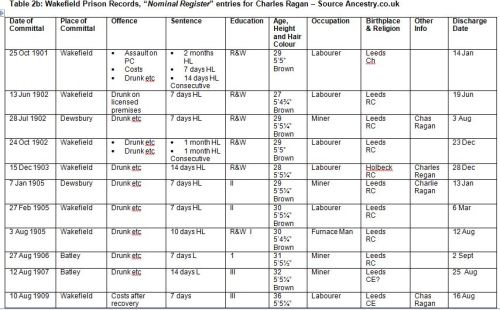

Looking at the censuses with this fresh information, Charles Joseph Ragan, to give him his full name, was born in Holbeck in 1869. He was the son of Irish-born coal miner John Ragan and his wife Sarah Norfolk, a local girl from Hunslet. The couple married in 1866 and by the time of the 1871 census the family was recorded living in Holbeck. Besides Charles other children included six year-old Hannah Norfolk, three year-old Thomas and infant daughter Sarah.

Looking at the censuses with this fresh information, Charles Joseph Ragan, to give him his full name, was born in Holbeck in 1869. He was the son of Irish-born coal miner John Ragan and his wife Sarah Norfolk, a local girl from Hunslet. The couple married in 1866 and by the time of the 1871 census the family was recorded living in Holbeck. Besides Charles other children included six year-old Hannah Norfolk, three year-old Thomas and infant daughter Sarah.