My last blog post covered a family connection to the Dewsbury tram disaster of 1912. However two years earlier the same branch of the family suffered as the result of another transport accident: but this one had fatal consequences. It involved Oliver Rhodes, the eight-year-old son of my great grandparents Jonathan Rhodes[1] and Edith Aveyard.

Jonathan and Edith married at Woodkirk Parish Church on 14 August 1897 and soon after settled at Healey Croft Terrace, East Ardsley. Jonathan was diabetic in an age before insulin. But despite his poor health he worked as a coal miner. They had five children. Alice was born in 1897; Ethel in 1899; Oliver in 1902; William Henry Bastow in 1903 and Pauline (my nana) in 1905. William died of meningitis in June 1907 and was buried in St Michael’s Churchyard, East Ardsley. It was the church in which their youngest children were baptised[2]. Shortly afterwards the family moved to Morley and in 1910 lived on Garnett Street[3].

Oliver too had health problems. Despite being generally fit and strong, he had extremely poor eyesight, a condition which in his short life necessitated five operations at Leeds Infirmary. Despite these issues he was able to attend school.

According to oral family history, on Saturday 8 October 1910 Edith struggled with a severe headache and eventually sent Oliver on an errand to get some medication. The “Morley Observer” report of the inquest makes no mention of this. Instead their coverage states Oliver went out to play just after 5pm. Local children were in the habit of playing in an area of land known as America Moor, across from where the family lived.

However witness statements from Annie Newsome, who watched events unfold from the end of Co-operative Row[4] and William Dean North, standing with a cart at the end of Garnett Street, all place Oliver, alone, on the opposite side of Britannia Road[5], from America Moor. The 1908 OS map[6] below includes all the relevant locations. This was not the children’s normal play area so would perhaps indicate the possibility of an errand. And this is supported by the report in the “Batley Reporter”.

Map of Morley showing Britannia Road (scene of the accident) and other key locations such as America Moor, Garnett Street, Stump Cross Inn and Co-operative Road

Map of Morley showing Britannia Road (scene of the accident) and other key locations such as America Moor, Garnett Street, Stump Cross Inn and Co-operative RoadAccording to these witnesses, between 5.30-5.45pm[7] Oliver was walking along Britannia Road, on the causeway opposite his home. Some boys were on the other side of the road, which would be the America Moor side. Oliver began to cross towards the Garnett Street side, but halted to let three cyclists pass. They were heading in the Wakefield direction. Then he started to run to the other side, seemingly unaware that a motor car was almost upon him.

The chauffeur-driven vehicle belonged to Mr West, a Keighley chemist. He invited a Mr Arthur Emmett and two friends[8] to take a run in the car to watch Wakefield Trinity play Keighley in a game of rugby at Belle Vue. They were returning home in the Bradford direction after watching the match and stopping off post-game at the Alexandra Hotel, Belle Vue.

The chauffeur employed by Mr West, Willie Sugden, had held a licence for six years without incident. When he got to the stretch of Britannia Road in the vicinity of the Stump Cross Inn where the accident occurred[9], the three cyclists passed him. He noticed a cart on one side of the road and some boys playing at the other. Other than these distractions the road was quiet.

The stretch of road where the accident happened, looking towards The Stump Cross Inn (bottom left) – taken at 5.45pm 8 October 2015

The stretch of road where the accident happened, looking towards The Stump Cross Inn (bottom left) – taken at 5.45pm 8 October 2015Willie sounded his horn fearing the children might run out. But he failed to see young Oliver on the other side from them, in the process of crossing in front of the car. Front-seat passenger, Arthur Emmett, had though. He urged Willie to brake. Although the car was estimated to be travelling at no more than 12 miles per hour, just faster than a horse-trot, it could not stop in time and knocked Oliver down. Two of the wheels passed over his head.

Whether Oliver’s weak eyesight meant he failed to see the car or caused him to misjudge the distance will never be known. One theory was in avoiding the cyclists Oliver ran in the way of the car.

At 5.45pm the family were told of the accident by a boy the Morley newspaper mistakenly describe as Oliver’s brother. It was more than likely his cousin Arnold Rhodes. Jonathan went out and met the occupants of the car carrying his unconscious son home. They gave Jonathan £1 in order to procure anything necessary.

Police Constable Newsome and Mr Davey, one of the car occupants, immediately drove to summon Dr Firth at Cross Hall. They returned with Dr Stevens[10], a locum. Inside he found Oliver lying unconscious on the couch. But it was a hopeless case. Oliver died shortly before 8pm as a result of a fracture at the base of his skull.

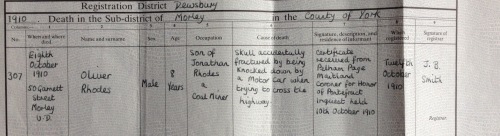

Oliver’s Death Certificate

Oliver’s Death CertificateThe inquest, which was held at Morley Town Hall on 10 October, returned a verdict of “Accidentally killed by being knocked down by a motor car whilst trying to cross the road”.

Willie Sugden was exonerated of all blame and his licence returned. After the inquest the car occupants once again went to Oliver’s home to offer the family financial assistance.

On 11 October Oliver was buried alongside his brother William at St Michael’s, East Ardsley. The grave is unmarked. Below is the receipt for Oliver’s burial – £1 3s. It is to be hoped that the financial assistance proffered by the Keighley men at least covered the medical and funeral costs.

Burial Receipt

Burial ReceiptThe thing which comes across above all else in the otherwise factual inquest reports is Jonathan’s utter grief, shock, bewilderment and raw emotion. This is clear from just one phrase at the inquest, held less than two days after his son’s death, when he said he “was too much troubled to remember whether anything was said by the man who carried him [Oliver] home”.

The other point is the discrepancies in the newspaper reports, the need to analyse them carefully and, if at all possible, compare a number of sources (including as many newspapers as available).

Sources:

- Batley Reporter – 14 October 1910

- Death Certificate – Oliver Rhodes

- Marriage Certificate – Jonathan Rhodes & Edith Aveyard

- Morley Observer – 14 October 1910

- Ordnance Survey Map of Morley (published 1908) – re-published by Alan Godfrey. Also on the National Library of Scotland website http://maps.nls.uk/

- St Michael’s Parish Church, East Ardsley – baptism and burial registers. Available now on Ancestry UK http://home.ancestry.co.uk/

- St Michael’s Parish Church, East Ardsley – burial receipt

[1] Jonathan was the son of Elizabeth Hallas, sister of Violet Jennings. Elizabeth was born a few months before Ann Hallas and Herod Jennings married.

[2] Eldest child Alice was baptised at Woodkirk Parish Church. Pauline’s baptism took place at St Michael’s in July 1907 when she was two. An event presumably prompted by the death of her brother the month before.

[3] The Morley Observer is less precise giving the home address as Britannia Road.

[4] It is possible that this location should be Co-operative Road.

[5] A portion of the Bradford and Wakefield main road.

[6] Surveyed in 1889-92, revised in 1906, published 1908.

[7] Witness estimates generally put the time of the accident as 5.40pm.

[8] The combined newspaper reports identified the three passengers as master plasterer Arthur Emmett and his brother; and landlord of the Stocksbridge Hotel, Keighley, Mr W Davey.

[9] From maps and eyewitness accounts I estimate the accident happened in the area between the Stump Cross Inn and the Cross Keys.

[10] Another report has an alternative spelling, Dr Stephen.

GRO Picture Credit:

Extract from GRO death register entry for Oliver Rhodes: Image © Crown Copyright and posted in compliance with General Register Office copyright guidance.