Have you ever stumbled across what could be the words of your ordinary, working-class ancestors? The type who never usually feature in records beyond those associated with births, marriages and deaths? Words which well over 150 years later hit you like a hammer blow? You can imagine them speaking those words, and through them have a totally unique and unexpected window into their lives. Here is my experience.

Several years ago, when reading extracts of depositions contained within the First Report to the Children’s Employment Commission [1] looking at mines, a series of familiar names featured. Brief extracts were published in various parts of the 1842 Report.

The names were:

- J. Ibbetson, collier in poor health, age 53, Birkenshaw;

- John Ibbetson, 13½-years-old. No further details;

- James Ibbetson, aged about twenty, Collier at Mr Harrison’s Pit, Gomersal whose two sisters aged twelve and a half and between eight and nine worked as his hurriers; and

- Elizabeth Ibbetson, a hurrier at Mr Harrison’s Pit, Gomersal. Age not stated.

Because they appeared in distinctly separate parts of the Report, there was nothing to indicate if this was one or more families. But the names stood out because my 4x great grandfather, Jonathan Ibbetson (and variant spellings [2]), was a coal miner. Born in around 1788 in Halifax, by the 1841 census (name recorded as Hibbeson) [3] he was living at Tong More Side, Birkenshaw cum Hunsworth. The household comprised of Jonathan Hibbeson (50), a coal miner; William (20); Martha (15); John (14); Bettey (11); and Mary (9) [4]. Jonathan’s wife, Elizabeth Rushworth, who he married on 25 February 1811 in Halifax Parish Church, which is dedicated to St John the Baptist [5], is not in the census household. I have not traced her burial yet, but the possibility is she was dead by 1841. In the 1851 census, which provides more family relationship details, Jonathan is described as a widower.

At the time of Jonathan and Elizabeth’s marriage their abode was Ovenden. They subsequently lived in Queensbury, and possibly the Thornton area, before Jonathan ended up in Birkenshaw. A family with non-Conformist leanings their children included:

- Hannah, baptised 20 August 1811 at Mount Zion Chapel, Ovenden. Other information includes she was the daughter of Jonathan and Betty Ibbitson of Swilhill [6];

- John, son of Jonathan and Betty Ibbeson of Swilhill. Baptised 28 August 1814 at Mount Zion Chapel, Ovenden [7]. Possible burial 7 March 1815, age 9 months at the Parish Church of St Mary’s Illingworth. Abode Ovenden [8];

- James, baptised 16 June 1816 at Mount Zion Chapel, Ovenden. The son of Jonathan and Betty Ibbetson of Skylark Hall [9];

- William, born on 4 August 1821 and baptised at Mount Zion Chapel, Ovenden on 5 September 1821, son of Jonathan and Betty Ibbotson of Bradshaw Row in Ovenden [10]. Points to note, if being precise he was two months shy of 20 in the 1841 census, so technically his age should have been rounded down to 15; Also, although his earlier census birthplaces are given as Thornton and, bizarrely, Birstall, by 1871 and 1881 it is corrected to Ovenden;

- Martha, my 3x great grandmother. I’ve not traced her baptism, but other sources indicate she was born in around 1824/25 in either Bradford, Thornton or Queensbury, depending on the three censuses where her birthplace is given. Why, oh why aren’t ancestors consistent with information?

- John was born in around 1827 and his burial is in the parish register of St Paul’s, Birkenshaw on 15 February 1844, age 17. He is recorded as being the son of collier Jonathan Ibbetson [11];

- Elizabeth (Bettey in the 1841 census) was born in around 1830 likely in Queensbury, although again the censuses for her vary [12]. She was baptised at St Paul’s, Birkenshaw on 25 December 1844. Her parents are named as Jonathan and Elizabeth Ibbotson [13]; and

- Mary was born in around 1832 in Queensbury or Thornton [14]. She was baptised at the same time as sister Elizabeth [15].

There was possibly another son named Joseph, born circa 1820. More of him, and why I believe he is linked to the family, is perhaps the subject for a later post.

I never have much opportunity to research my family history to the extent I would wish nowadays. It was only earlier in July 2019 that I finally got around to investigating the Children’s Commission Report further. This meant a visit to Leeds Central Library’s Local and Family History section where the volumes containing appendices to the Report are held [16]. These contain the statements of the various witnesses who gave evidence to the Sub-Commissioners, extracts of which were used in the Report.

They make powerful, and emotionally challenging, reading. In order not to dilute their impact I’ve published in full the Ibbetson statements, and that of the Gomersal pit owner in whose mine they worked. These statements were given to Sub-Commissioner Jelinger C. Symons in 1841. He investigated the West Riding coal mines (excluding those in the Leeds, Bradford and Halifax areas).

No. 263. – James Ibbetson, aged about 20. Examined at Mr. Harrison’s Pit, Gomersal, May 26, 1841: –

I am a collier. There are three hurriers [17] in the pit; two are girls; they are my sisters. They hurry for me. None hurry here with belt and chain [18]. The oldest is 12½. The youngest is between 8 and 9. She has been working ever since she was 6 years old. They have both hurried together since she was 6 years old. Sometimes when I have got my stint I come out as I have done to-day, and leave them to fill and hurry. I have gone down at 4 and 5 and 6, and the lasses come at 8, and they get out about 5. They stop at 12, and if the men have some feeling they let them stop pit an hour, but there are not many but what keep them tugging at it. The girls hurry to dip [19]. The distance is 160 yards. The corves weigh 3½cwt. each, and they hurry 22 on average. I don’t think it proper for girls to be in pit. I know I could get boys, but my sisters are more to be depended on; they are capital hurriers. Some hurriers are kept to work with sharp speaking, and sometimes paid with pick-shaft, and anything else the men can lay their hands on. I saw two people killed at Queen’s Head, where they are less civilized than here; and the rope slipped off the gin and jerked and broke, and they were killed. At Harrison’s other pit there are eight boys.

No. 264. – John Ibbetson. Examined May 26, 1841, at Mr. Harrison’s Pit, Gomersal: –

I am 13½. I hurry alone. I go down at 7, and sometimes at 8. Sometimes we work a whole day, and then it’s 5 when we come out. I stop at 12, and my sisters too, for an hour and a half. I like being in pit. I’ve been down 6 year or better. I thrust with my head [20] where the coals touch the top of the gates and then we have to push. In all the bank-gates they don’t cut it down enough. I have been to Sunday-school. I stop at home now, I’ve no clothes to go in; I stop in because I’ve no clothes to go and lake [21] with other little lads. I read spelling-book. I don’t know who Jesus Christ was; I never saw him but I’ve seen Foster who prays about him. I’ve heard something about him, but I never heard that he was put to death.

No. 265. – Mr Joseph Harrison. Examined May 26, 1841, at Gomersal:-

I don’t employ the hurriers; they are entirely under the control of the men, but when they quarrel I interfere to prevent it. I don’t approve of girls coming. I allow two as a favour. I have four pits and 18 children. They thrust two together when they are little. In the bank-gates the coal will catch the roofs sometimes, because we leave seven or eight inches inferior. We don’t require children younger than 10 years, as far as our experience. They can do very little before they are at that age, and I would as lief be without them. We could do if they were to allow us to draw coals for eight hours, with an additional hour for meals. If they could thus make colliers work regular it would be a good thing. They will sometimes work for 12 or 13 hours, and then they will lake perhaps. The getters don’t leave the children to fill and hurry here after they come out of pit, except it be a corf or two. If hurriers are prohibited from working till they are 10, I don’t know whether we could get enough or not.

No. 266. – Elizabeth Ibbetson. Examined at Mr Harrison’s Pit, Gomersal, May 26, 1841:-

I am 11 ½ years old. I don’t like being at pit so weel [sic]; it’s too hard work for us. My sister hurries with me. I’ve been two year and a half in this pit. It tires my legs and arms; not much in my back. I get my feet wet. I come down at 7 and 8. I come out at 4, and sometimes at 2, and sometimes stay till 6. I laked on Saturday, for I had gotten cold. I am wet in the feet now; they are often wet. We rest an hour one day with another, but we stop none at Saturdays. I push the corf with my head, and it hurts me, and is sore. I go to Sunday-school to Methodists every Sunday. I read A B C. I’ve heard I shall go to heaven if I’m a good girl, and to hell if I’m bad; but I never heard nought at all about Jesus Christ. We are used very well, but sometimes the hurriers fall out, and then they pay us. My father works at pit.

No. 267. – John Ibbetson, aged 53. Examined at Birkenshaw, near Birstall [undated]: –

I have been 45 years in the pits. I am the father of the children you have examined at Mr. Harrison’s pit. I have had three ribs on one side and two on the other broken, and my collar-bone, and my leg skinned. My reason for taking these girls into the pit is that I can get nought else for them to do. I can’t get enough wages to dress the boys for going to school. I get 5s. 6d. For the girls, and I and my two sons earn 17s. 6d. on average a-week. I am done up. I cannot addle [22] much. The eldest girl does nothing at all. We get potatoes and a bit of meat or bacon when they come out of the pit. I knew a man called Joseph Cawthrey, who sent a child in at 4 years old; and there are many who go to thrust behind at that time, and many go at 5 and 6; but it is soon enough for them to go at 9 or 10; the sooner they go in the sooner their constitution is mashed up [23], I have been 13 hours in a pit since I have been here, but 8 hours is plenty. The children went with us and came back with us; they worked as long as we did. The colliers and the children about here will be 12 hours from the time they go away till they come home. They could not addle a living if they were stinted to work to 8 hours at present ages. The children don’t get schooling as they ought to have. I cannot deny it. I cannot get the means. I have suffered from asthma, and am regularly knocked up. A collier cannot stand the work regularly. We must stop now and then, or he would be mashed up before any time. We cannot afford to keep Collier-Monday [24] as we used to do.

The statements are far more detailed than the brief extracts in the published Report, which is a synthesis of masses of evidence. In fact not all statements made the final cut, so if your ancestor is not mentioned in the final Report it is still worth checking the appendices.

The full statements now confirm that a 53-year-old miner John Ibbetson along with sons James (aged about 20) and John (13½), and daughter Elizabeth (11½ or 12½ depending on deposition) plus another unnamed daughter aged between 8 and 9, worked at Mr Harrison’s pit in Gomersal. They confirm the absence of a mother. They also confirm an older, unnamed, daughter who “does nothing at all.” This older daughter would fit with Martha, my 3x great grandmother. Presumably she is taking care of the household chores, in place of her mother. Methodism is indicated, in terms of religion, but the children only have a sketchy concept of the Bible. There is a Birkenshaw link – which is where John Ibbetson provided his testimony. Gomersal to Birkenshaw is about two miles, so perfectly feasible for a work commute. It is also clear John is in poor health and the family is struggling to make ends meet.

The desperation in the statement of the father is palpable. The family managed as best they could. It appears the girls were given priority for clothes, with Elizabeth rather than John being sufficiently well-dressed to attend Sunday School, and their father admitting as much.

There is also the acknowledgement that sending the girls (and even young boys) to work down in the coal mines was not something their father would do through choice – but the income was needed for them to keep going, to keep the family together. There was, I guess, always the dreaded spectre of the workhouse with its associated stigma that somehow you had failed your kith and kin, alongside the threat of family separation. You did all you could to avoid it. If it meant children working, so be it.

It must also be said it was believed that in order to get children accustomed to mine work, and to be able to progress, they needed to be introduced to it at an early age. And, in this pre-compulsory education era, work (even in mines) also offered some measure of childcare – especially if there was no mother, or a working mother.

There is the sense of pride by James in the work his sisters undertook. It is to be hoped that he was a miner who looked kindly on them whilst they toiled, because this attitude could have a huge impact on the lot of the young hurrier. For instance, did he notice when they were tired and, if so, did he let them rest for a little while when they arrived at his bank, and in doing so did he fill the corve himself? Did he help push off the laden corves? His sister Elizabeth indicates she was treated well. And still there remains the image in my mind of the tired, wet Elizabeth with aching limbs and head sore from pushing the corve, yet wanting to be a good girl so she could go to heaven.

And then there is young John, accepting his lot, taking simple pleasures from ‘laking ’, and enjoying his work despite its hardships. His innocent words about never having seen Jesus Christ are echoing in my ears.

But is this my family? The ages for children John, Elizabeth and Mary given in the Commission evidence correspond with the ages ascertained from my family history research for my Ibbetson ancestors. The age of their father John roughly matches that of my 4x great grandfather Jonathan, with 53 equating to a year of birth circa 1788. It also is distinctly possible that John could have been used in the witness statement rather than Jonathan. I’ve reviewed details for a sample of witnesses elsewhere and cross-matched against the 1841 census. From this there is evidence that names do not always match up exactly with this census; and ages do not in all cases match precisely with those given in the 1841 census for under 15’s. [25].

The 1841 census, taken on 6 June, was only a couple of weeks after the Ibbetsons gave evidence to the Commission. As illustrated earlier, at that time the census household comprised of Jonathan, William, Martha, John, Bettey and Mary. I have gone through the 1841 census for the Birkenshaw and Gomersal areas page by page and can find no other Ibbetson (and variant) family who would fit as a unit with the names of those giving evidence. I suppose there is always a remote possibility the family giving evidence left the area in between their Commission interviews and the census date; or even that they were for some reason missing from the census. But, taken with other evidence, I think this is unlikely.

But there remains one major anomaly which makes me hesitate from saying with absolute certainty this is my family giving evidence to the Children’s Commission. It is the discrepancy with an approximately 20-year-old son named James. Although Jonathan did have a son named James, he is not present in the 1841 census household. In any case he would be around 25, not 20. The implication from the Commission statement is the son who gave evidence is still at home and contributing to the family income. Yet it seems a big stretch though to think the name James might be recorded as William. This is the one piece of conflicting evidence I have been unable to resolve.

Neither have I definitively discovered what happened to James. I have traced no death and, so far, I have two living candidates for him – but neither are totally satisfactory. One is married to Ann (née Binns) [26] and living in Birkenshaw in 1841 and 1861 (Thornton in 1851). At the moment he is seeming the most likely, although I’ve yet to find his marriage. My hope was it would be in the Civil Registration era and name his father. But I am still searching. This James died in a mining accident in November 1870 [27], with his age given as 56 [28 and 29], so not quite a fit. His census birthplace is Thornton [30], so not a match for the baptism details. His children included Margaret, Hannah, Ellen, Emma, John, Sophia, Mary, Betsy and Annice.

The other James Ibbetson married Priscilla Robinson in Bradford Parish Church in December 1833 [31] and is living in Thornton in 1841. I have some issues with this one. These include that whilst his bride’s entry in the parish register notes she is a minor and marries with consent, his details do not. If he was baptised shortly after his birth he too would be a minor. I suppose he may not have been baptised as a baby, but it is a niggle. As is the fact the likely death for him, registered in the December Quarter of 1847 gives his age as 35 [32], equating to a year of birth circa 1812. On the plus side is the naming pattern for his children which include some familiar ones – William, Martha, Mary and Betty, alongside the less familiar Joshua and Nancy.

It is here I have one final piece of evidence to throw into the mix, and one which I feel tilts the balance towards it being my family. It comes in the 26 May 1841 Commission statement of ‘James’ Ibbetson when he says “I saw two people killed at Queen’s Head…”

Queensbury, midway between Halifax and Bradford, and a location which in censuses is intermittently cited as the birthplace of various younger Ibbetsons, was not known as such until 1863. Prior to that it was Queenshead. In fact, in the 1861 census Elizabeth’s birthplace is given as Queenshead, Halifax [33]. And it is this which provides yet another link to my Ibbetson family and makes me believe, on balance, it is them who provided statements to the Commission.

This combination of locational links along with the similarity in names, ages, religion, motherlessness, plus my exhaustive search of the 1841 census for any alternatives in the Birkenshaw/Gomersal areas, all add to the weight of evidence supporting this being my family.

So, what happened to my Ibbetson ancestors?

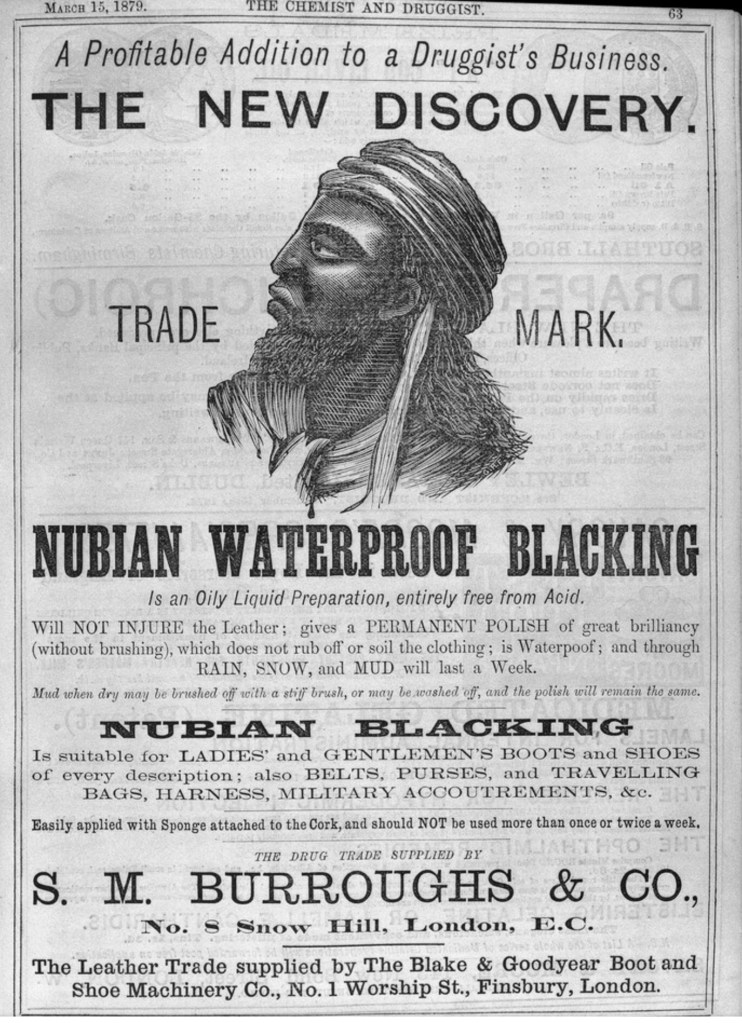

Jonathan’s health was “mashed up”. Whereas for the burial of his son John in 1844 he is still a collier, by the baptism of daughters Elizabeth and Mary at the end of the year he is a labourer. The 1851 census states he was ‘formerly a miner’. He died on 21 February 1857 at Dewsbury Union Workhouse of bronchitis. His occupation recorded on his death certificate is ‘blacking hawker’ [34].

Blacking was used for cleaning, polishing and – crucially – waterproofing boots and shoes. Such footwear was not the disposable item of today. These were precious, valuable essentials for everyday life which had to last. If you didn’t have them you couldn’t work. If you couldn’t work, you didn’t have money to support the family. To my mind 19th century blacking is like petrol and diesel of today. Essential for getting to and from work, as well as actually doing the job. So often boots feature amongst stolen items in court reports. Reading school log books and countless children are unable to attend school, particularly in winter weather, through lack of suitable footwear. They were costly and had to be cared for. Blacking was part of their regular maintenance regime. In 1824 the 11-year-old Charles Dickens was sent out to work in Warren’s Blacking Factory, pasting labels onto individual pots of boot blacking polish, a job which had a significant impact on his life. Blacking was also used widely around the Victorian home for polishing the kitchen range and grates in fireplaces. Jonathan, no longer fit for strenuous mining work, was now selling this essential commodity.

Jonathan’s burial is recorded in the register of Dewsbury Parish Church on 25 February 1857 [35].

Of the children at home in 1841:

- William married twice, and died in 1890. His burial is recorded in the register of Birkenshaw St Paul’s on 5 March 1890 [36];

- John died in 1844, as mentioned earlier. He was only 17;

- Martha married Joseph Hill at Hartshead Parish Church on 21 November 1842 [37] and died 4 February 1881 [38]. Her burial is in the Drighlington St Paul’s register on 7 February 1881 [39];

- Elizabeth married Joseph Haigh on 1 April 1850 at St James, Tong [40] and died in 1883. Her burial is entered in the Birkenshaw St Paul’s Register on 31 March 1883 [41]; and

- Mary married James Noble at St Peter’s Bradford parish church on 25 December 1850 [42]. The newly married couple are living in Birkenshaw with her father in the 1851 census. She died in 1893, with the Allerton Bywater Parish Church burial register noting the burial date as 19 January 1893 [43].

This tale also goes to show family history research is often not neat and simple with all loose ends tied up. It can be a messy affair, with partial and contradictory information and many negative of eliminatory searches in order to try achieve the genealogical proof standard. It can be a long, ongoing process. And, as such, I do not discount at a later date unearthing more information which might conclusively prove (or demolish) my case.

I would like to conclude by saying a special thank you to the staff at Leeds Local and Family History Library for their help in locating a copy of the Children’s Employment Commission: Appendix to the First Report of Commissioners, Mines: Part I: Reports and Evidence from Sub-Commissioners, Volume 7. This work was key to my research, and illustrates once more why we should love, use and cherish our local libraries as a unique, integral, and ‘accessible for all’ resource.

This is one of a series of four posts on the evidence of the Sub-Commissioners. The others are:

- The Shame of a Workhouse – An Infant Down the Pit;

- Anne Lister’s Pit Children; and

- Mining Genealogy Gold – A Hidden Gem in Leeds Library.

Notes:

[1] Children’s Employment Commission – First Report of the Commissioners: Mines. London: Printed by William Clowes for H.M.S.O., 1842.

[2] The possibilities are endless. Examples include Ibbetson, Ibbotson, Ibotson, Ibbitson, Ibberson, Ibbeson, Hibbison, Hibetson, Hibberson etc.

[3] Hibbeson household, 1841 Census; accessed via Findmypast; original record at The National Archives, UK, Kew (TNA), Reference HO107/1291/4/12/17.

[4] Note this census rounded down to the nearest five years those aged 15 and over.

[5] Jonathan Ibbotson and Elizabeth Rushworth’s marriage entry, parish register of St John the Baptist, Halifax; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1512-1812 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, New Reference Number: WDP53/1/3/13.

[6] Hannah Ibbitston’s baptism, Mount Zion Chapel, Ovenden; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1970 [database on-line]; original record at TNA, General Register Office (GRO): Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths surrendered to the Non-parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857; Class Number: RG 4; Piece Number: 3408.

[7] John Ibbeson’s baptism, Mount Zion Chapel, Ovenden; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1970 [database on-line]; original record at TNA, GRO: Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths surrendered to the Non-parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857; Class Number: RG 4; Piece Number: 3408.

[8] John Ibbotson’s burial entry, burial register of Illingworth St Mary; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1985 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, New Reference Number: WDP73/1/4/1.

[9] James Ibbetson’s baptism, Mount Zion Chapel, Ovenden; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1970 [database on-line]; original record at TNA, GRO: Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths surrendered to the Non-parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857; Class Number: RG 4; Piece Number: 3408.

[10] William Ibbotson’s baptism, Mount Zion Chapel, Ovenden; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1970 [database on-line]; original record at TNA, GRO: Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths surrendered to the Non-parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857; Class Number: RG 4; Piece Number: 3409.

[11] John Ibbetson’s burial entry, burial register St Paul’s, Birkenshaw; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1985 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, Wakefield, Yorkshire, England; New Reference Number: WDP90/1/3/1.

[12] Bradford, Queenshead – Halifax, Thornhill, and Queensbury in the censuses between 1851-1881.

[13] Elizabeth Ibbotson’s baptism entry, baptism register St Paul’s, Birkenshaw; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1910 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, Reference Number: WDP90/1/1/1.[14] 1861 and 1871 censuses indicate Thornton; 1881 and 1891 Queensbury. The 1851 states Halifax.

[15] For Mary Ibbotson’s baptism, see [13].

[16] Children’s Employment Commission: Appendix to the First Report of Commissioners, Mines: Part I: Reports and Evidence from Sub-Commissioners, Industrial Revolution Children’s Employment, Volume 7. 141 Thomas St., Dublin: Irish University Press, 1968.

[17] Locally, hurriers conveyed coal from where it was hewn to the shaft by means of corves (wagons, usually small-wheeled), either dragging or pushing their loads. Often it meant running as quickly as possible up an incline with a full load.

[18] The hurrier wears a belt around their waist and a chain, attached to the corve (the wagon for transporting the coal). In the thinner seams this chain would runs between the child’s legs and, on all fours, they pull the coal corves like an animal.

[19] Coal lies at an inclined plane with the downward inclination known as the dip in Yorkshire.

[20] To push the coal corves with your head.

[21] To idle, or pass the time away.

[22] To earn.

[23] Disabled or worn out.

[24] Collier-Monday was the tradition of an unofficial, customary holiday which long existed in the coal mining industry. The Bolton Evening News of 23 February 1905 stated “It is the custom of miners to have one day’s play a week, which has gained for it the name of “Colliers’ Monday,” and that this is recognised is shown by the fact that notices placed at some pit heads state that men absenting themselves for two days are liable for dismissal…”

[25] I have used under 15s as the benchmark as the convention typically (but not exclusively) used in the 1841 census is to round down those aged over 14 to the nearest 5 years.

[26] Ann’s maiden name has been identified via the GRO indexes for the births of the couple’s children.

[27] Bradford Observer, 21 September 1870.

[28] James Ibbotson, GRO Death Registration, Bradford, September Quarter 1870, Volume 9b, Page 13; accessed via FreeBMD.

[29] Death of James Ibbotson, 17 September 1870; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk Web: UK, Coal Mining Accidents and Deaths Index, 1878-1935 [database on-line]; original data Coalmining Accidents and Deaths. The Coalmining History Resource Centre. http://www.cmhrc.co.uk/site/disasters/index.html

[30] 1851 census for James Ibitson; accessed via Findmypast; original record at TNA; Reference HO107/2311/165/16 and 1861 census for James Ibbitson, TNA Reference RG09/3403/127/3.

[31] James Ibbiston and Priscilla Robinson marriage entry, marriage register of Bradford St Peter Parish Church; accessed via West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1813-1935 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, Reference Number: BDP14.

[32] James Ibbotson GRO Death Registration, Bradford, December Quarter 1847, Volume 23, Page 135; accessed via the GRO website.

[33] 1861 census entry for Elizabeth Haigh; accessed via Findmypast; original record at TNA, Reference RG09/3403/114/11.

[34] Jonathan Ibbitson’s Death Certificate; GRO Reference Dewsbury, March Quarter 1857, Volume 9B, Page 322, age 70.

[35] Jonathan Ibbotson’s burial entry, burial register of All Saints Parish Church, Dewsbury, age 70; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1985 [database on-line]; original record West Yorkshire Archive Service, New Reference Number: WDP9/52.

[36] William Ibbotson’s burial entry, burial register of St Paul’s, Birkenshaw, age given as 65; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1985 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, New Reference Number: WDP90/1/3/2.

[37] Joseph Hill and Martha Ibbotson, Marriage Certificate; GRO Reference Halifax, December Quarter 1842, Volume 22, Page 197.

[38] Martha Hill, Death Certificate; GRO Reference Leeds, March Quarter 1881, Volume 9B, Page 355, age 57.

[39] Martha Hill’s burial entry, burial register of St Paul’s, Drighlington; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1985 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, New Reference Number: WDP124/1/4/3.

[40] Joseph Haigh and Elizabeth Ibbeson’s marriage entry, marriage register of Tong, St James Parish Church; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1813-1935 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, no reference provided online.

[41] Elizabeth Haigh’s burial entry, burial register of St Paul’s, Birkenshaw, age given as 56; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1985 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, New Reference Number: WDP90/1/3/2.

[42] James Noble and Mary Ibbotson’s marriage entry, marriage register of St Peter’s, Bradford Parish Church; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1813-1935 [database on-line]; original record at West Yorkshire Archive Service, Reference Number: BDP14.

[43] Mary Noble’s burial entry, burial register of Allerton Bywater Parish Church, age recorded as 59; accessed via Ancestry.co.uk, West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1985 [database on-line]; original record West Yorkshire Archive Service, New Reference Number: RDP3/3/1.

Years ago I bought dad a memory journal to complete. He never did. It’s a thing a bitterly regret he never got round to doing. It would have been a precious legacy to all his descendants for ever more, now he’s no longer around to ask. It would have been a much-cherished connection to him and his life through his written words. As it is, I’m the family history recorder, so now his life is viewed through my memories, my prism. One step removed.

Years ago I bought dad a memory journal to complete. He never did. It’s a thing a bitterly regret he never got round to doing. It would have been a precious legacy to all his descendants for ever more, now he’s no longer around to ask. It would have been a much-cherished connection to him and his life through his written words. As it is, I’m the family history recorder, so now his life is viewed through my memories, my prism. One step removed.