Once you get into your family history, you progress from names and dates to finding about the lives and times of your ancestors. Their employment is a significant part of this discovery process, because it formed a big part of their lives. And although not quite cradle to grave, this work was often from early childhood.

The first time l looked at censuses in any detail was over 30 years ago to produce an analysis of child employment in the silk industry between 1815-1871. Although I do have ancestors in the textile industry, so far I’ve not discovered any in the silk branch.

It was also the first time I looked at the various parliamentary inquiries into child employment, and discovered what a wealth of information they supplied about working conditions and employment practices. And this in the words of those involved – employers and employees. So a name-rich source to which you may find an ancestor gave evidence. But even if you don’t find your ancestor named, they provide a fantastic insight into their work and conditions.

I’m going to share a summary of this essentially old pre-Internet piece of research (updated with some more recent information) in case it helps anyone else: Either directly for those with silk industry antecedents; or indirectly to show what type of occupational information can be gleaned from primary sources.

It is quite lengthy so I will split it into four posts. The research covers:

- a general overview of the industry;

- the nature of the work; and

- the reasons for, and decline of, child employment in this area.

I will also look at the Factory Acts, and the reasons why initially they only had the partial inclusion of child silk workers.

Background

I chose 1815 as the starting point, as the end of the Napoleonic Wars marked a significant date for the English silk industry, paving the way for free trade and the lifting of protectionism. The years 1815-1820 also marked a period of recession with an influx of returning soldiers seeking employment driving wages down. And, although there was protectionism at this start point, more goods were sneaking in to the country once the Napoleonic Wars ended. 1871 is the finishing point as it coincides with the first census after the passing of the 1870 Education Act.

Silk weaving reached England on a small scale in the mid-fifteenth century. It developed in the mid-sixteenth century when Spanish religious persecutions forced Flemish weavers to seek refuge in the Spitalfields area of London. However it was not until the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which forced the French Protestant Huguenots to flee the country, that the English silk industry took off in any big way. The refugees included many skilled silk workers from Tours and Lyons, and these too settled in the Spitalfields area.

In this period the industry was domestic in nature. Manufacturers employed weavers as outworkers and supplied them with yarn. These weavers then spun it on their own looms in their own homes or workshops and took the finished product back to the manufacturer who inspected and weighed it, docked money for imperfections, and paid the weaver.

With the patent in 1718 of Thomas Lombe’s silk machine, which converted the filaments of raw silk into yarns and threads, the final main obstacle to English silk production was removed. Previously the silk weaving industry had to import expensive thrown silk. Now the raw silk could be imported and then turned into thrown silk in England. A rapid expansion of the silk throwing industry followed the expiration of Lombe’s patent rights in 1732. This led to the increased development of purpose-built silk throwing and spinning mills.

Yet even after this date the home-based character of silk-weaving branch continued. Factory weaving did take place though, especially from the 1820s onwards when Jacquard mechanisms attached to looms enabled the weaving of ever more complex patterns. Often these were too large for a domestic situation. This, along with the development of power looms, led to an increase in factory based weaving bringing the processes of silk throwing (spinning), warping, dyeing and weaving under one roof.

The protectionist attitude of the attitude of the British government meant between 1765-1826 fully manufactured silk imports were prohibited and duties on other silks were proportionately high. This gave an impetus the English industry. However this protectionism came to an end in 1826 when the importation of foreign silk goods became legal. Despite the levy of a duty of around 30% on Continental goods, it still posed a treat to the English industry, especially given the superior quality of French silks.

The main areas of the silk industry in the 19th century were Lancashire and Cheshire, particularly around Manchester and Macclesfield. Other significant centres included Derby, London and Coventry.

How many children in the silk industry and what did they do?

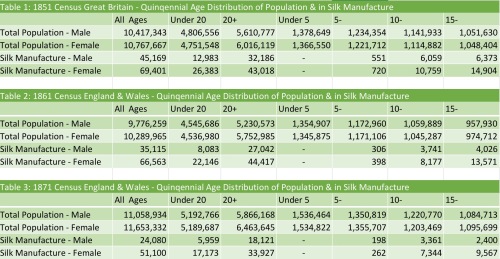

For this I looked at the census figures as well as various Select Committees and Royal Commissions investigating child employment in general. The numbers of children involved in silk manufacturing compared to the overall total population are shown in Tables 1-3. Whilst Table 1 is not directly comparable, being for Great Britain rather than England & Wales, it is illustrative. They show that the silk industry underwent a gradual but noticeable decline in adult as well as child employment. Numbers were skewed towards female operatives. Also in 1851 and 1861, when looking at overall data, the peak age for those employed in silk manufacture across both sexes was the 15- Quinquennial band.

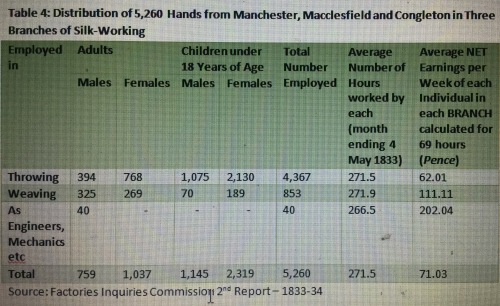

Table 4, from the Factories Inquiry Commission supplementary report of 1834, shows figures from a sample of silk factories in Manchester, Macclesfield and Congleton employing 5,260 operatives. Children were almost exclusively employed in the throwing departments. Their principal job was tying knots when the silk thread broke, each child being in charge of a certain number of threads. Various Select Committees examining child labour in factories reported on this. In 1816-17 it was estimated that a child was in charge of about 20 threads; by 1831-32 this has doubled “on account of the competition which exists between masters; one undersells the other, consequently the master endeavours to get an equal quantity of work done for less money.” By the time of the 1866 report into children’s employment it was down to 12. The children also had an element of responsibility, being accountable for the thread which passed through their hands. This was high value especially when compared to others textiles. Even if the silk was of a good quality that it would not break so often, still a great deal of vigilance was required.

The children also had an element of responsibility, being accountable for the thread which passed through their hands. This was high value especially when compared to others textiles. Even if the silk was of a good quality that it would not break so often, still a great deal of vigilance was required.

A good description of the jobs children were employed in is provided by James Sharpley for the silk throwsters Messrs Brocklehurst who operated mills in Huddersfield and Macclesfield. As reported in the “Royal Commission on Children Employed in Factories: Supplementary Report” published in 1834 he described their work and progression. “The processes of silk working ascend in difficulties of management, winding being the first and easiest; it is best and cheapest performed by children under twelve years, and thus requires also the most numerous body of workers; about twelve years of age many of the most expert are advanced to the next and more difficult processes, that is, the girls to the cleaning the silk thread, doubling several threads together, etc; and at fourteen or fifteen many of the girls are again advanced to the winding and warping the dyed silk for the weavers, which are the highest kinds of employment; the boys at fourteen are often promoted to the throwing mills, and at sixteen many of them learn to weave silk.”

Spinning, twisting and throwing were all used to describe the formation of a rope-like twist of the silken filament, to give it strength. It could be undertaken by machine or hand. A description of the hand process can be found in Lord Ashley’s (the later Earl of Shaftesbury) Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Employment of Children. Sub-commissioner Samuel Scriven described it as such in 1841:

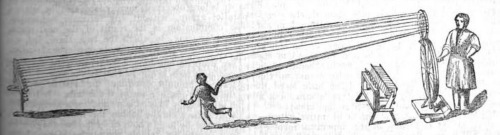

“For twisting it is necessary to have what are designated shades which are buildings of at least 30 or 35 yards in length, of two or more rooms, rented separately by one, two or four men having one gate and a boy called a helper… the upper storey is generally occupied by children, young persons or grown women as ‘piecers’, ‘winders’ and ‘doublers’ attending to their reels and bobbins, driven by the exertions of one man… He (the boy) takes first a rod containing four bobbins of silk from the twister who stands at his gate or wheel, and having fastened the ends, runs to the ‘cross’ at the extreme end of the room, round which he passes the threads of each bobbin and returns to the ‘gate’. He is despatched on a second expedition of the same kind, and returns as before, he then runs up to the cross and detaches the threads and comes to the roller. Supposing the master to make twelve rolls a day, the boy necessarily runs fourteen miles, and this is barefooted.“

Other jobs included “warp picking“, that is taking small defects out of the threads of warp before the weaver receives it; picking up waste; acting as helpers to weavers; or winding in a domestic situation.

For more information about the silk industry and its process “The Penny Magazine” Volume 12 April 1843 has an article “A Day at Derby Silk Mill.”

By this period the silk industry was principally a factory occupation. However it did still exist in a domestic form too. I’ve already referred to the weaving side. But silk throwing, the twisting of the tread of silk from the cocoon which takes the place of spinning, could still be undertaken in the home and sent to the factories for finishing and weaving. In the same 1834 publication J.S. Ward of Bruton, Somerset, mentioned that, besides his factory employees, he employed women and children winding and twisting silk in their own homes. The raw silk was given to the undertaker who would be engaged by the factory to return the silk full weight wound, doubled or twisted. These undertakers would in turn sub-let this work “hence it is that almost every house becomes a domestic manufactury, the husband, the wife, and their children….being occupied in the upper room which is devoted to the purposes of winding, doubling or weaving.” This practice still thrived into the 1860’s.

Besides being engaged as outworkers, children also played a part in handloom weaving. In the silk industry this still continued. For intricate, top quality pieces the handloom was superior to the power loom, due to the delicacy of the material. Outworkers who own looms worked by the piece for manufacturers. Children did not weave, but wound for the family. Children were generally taken from school at around the ages of nine or ten to do this.

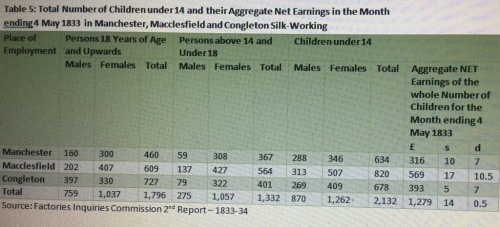

Looking at the growing factory branch of the industry, the ages at which children were employed is shown in Tables 1-3. However these are only from 1851 onwards and it is necessary to look at parliamentary papers to get an idea about ages prior to this year. In 1816-17 it appears that children worked from the age of six. By the raft of reports in the 1830’s this increased to eight. Table 4 (above) and Table 5 (below) give a flavour.

Even in the 1866 report into children’s employment H.W. Lord found cases of children aged eight working, though more typically it was nine. Some manufacturers in the 1830’s claimed their practice was not to take children under the age of nine or ten, but often parents would deceive them. George Senior, from the silk firm of William Harter in Manchester, said “the parents always tell the children to answer ‘going ten’ when they are asked their ages” and Stephen Brown, of Colchester, backed this up.

In my next post I will examine in more detail the ages, wages, working conditions and health of these child silk industry workers.

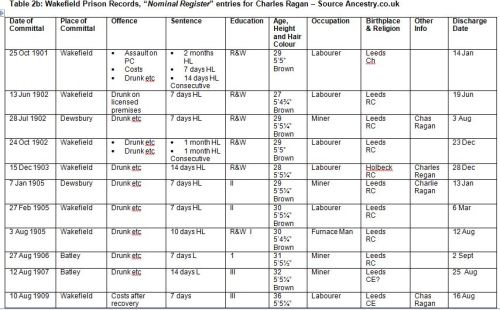

Looking at the censuses with this fresh information, Charles Joseph Ragan, to give him his full name, was born in Holbeck in 1869. He was the son of Irish-born coal miner John Ragan and his wife Sarah Norfolk, a local girl from Hunslet. The couple married in 1866 and by the time of the 1871 census the family was recorded living in Holbeck. Besides Charles other children included six year-old Hannah Norfolk, three year-old Thomas and infant daughter Sarah.

Looking at the censuses with this fresh information, Charles Joseph Ragan, to give him his full name, was born in Holbeck in 1869. He was the son of Irish-born coal miner John Ragan and his wife Sarah Norfolk, a local girl from Hunslet. The couple married in 1866 and by the time of the 1871 census the family was recorded living in Holbeck. Besides Charles other children included six year-old Hannah Norfolk, three year-old Thomas and infant daughter Sarah.