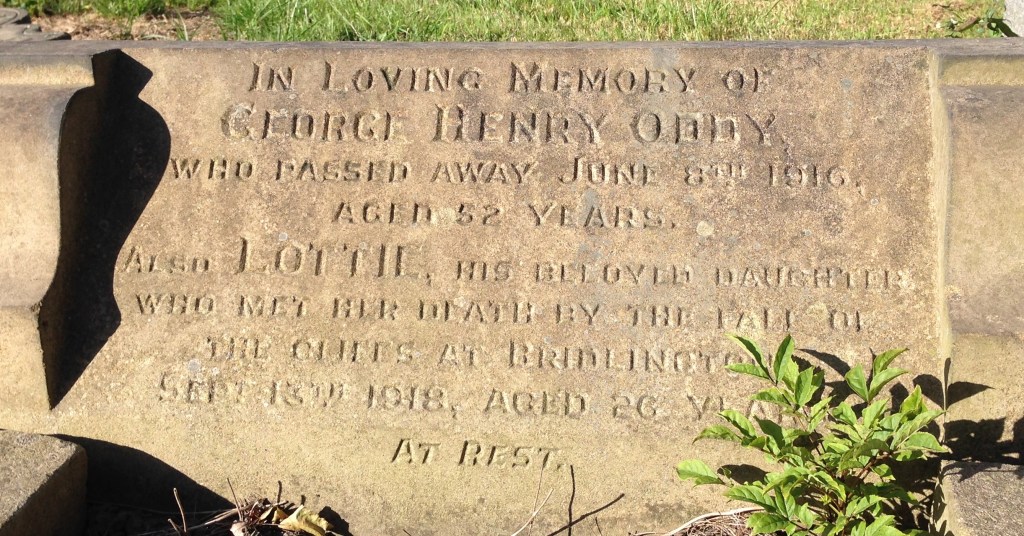

The intriguing inscription on Robert Shackleton’s impressive headstone in Batley cemetery commands attention.

After noting his death date of 24 September 1874, it reads:

HE WAS THE FIRST BOROUGH ACCOUNTANT OF

THIS TOWN AND HELD THE OFFICE TILL HIS DEATH

HIS UNIFORM INTEGRITY AND KINDNESS WON

FOR HIM THE ESTEEM OF ALL WHO KNEW HIM.

AND HIS SUDDEN REMOVAL UNDER

CIRCUMSTANCES MOST PAINFUL WAS THE

CAUSE OF DEEP SORROW TO A LARGE CIRCLE OF

RELATIVES AND FRIENDS.

What were these most painful circumstances causing his sudden removal? I had to investigate – and in the process discovered a dark Victorian tale, with an unexpected twist of compassion.

Robert Shackleton was born in Holbeck on 15 August 1817, the son of miller Richard Shackleton and wife Ann. His was a Quaker family and, rather than baptism, Robert’s birth was registered in the Brighouse Monthly Meeting book – though later in his life Robert switched from Quakerism and would be associated with the Methodist New Connexion denomination.

Subsequently, rather than milling, Richard’s primary job focus was as a proprietor of a grocer’s shop. Initially this was the trade his son followed, with the 1851 census describing Robert’s occupation as a grocer and watchmaker. At this point he was living in the Havercroft area of Batley, lodging with his brother George Walker Shackleton, also a grocer. George’s wife, Susan, was a daughter of Michael Sheard, one of Batley’s leading cloth manufacturers. So the Shackletons were already well-connected locally.

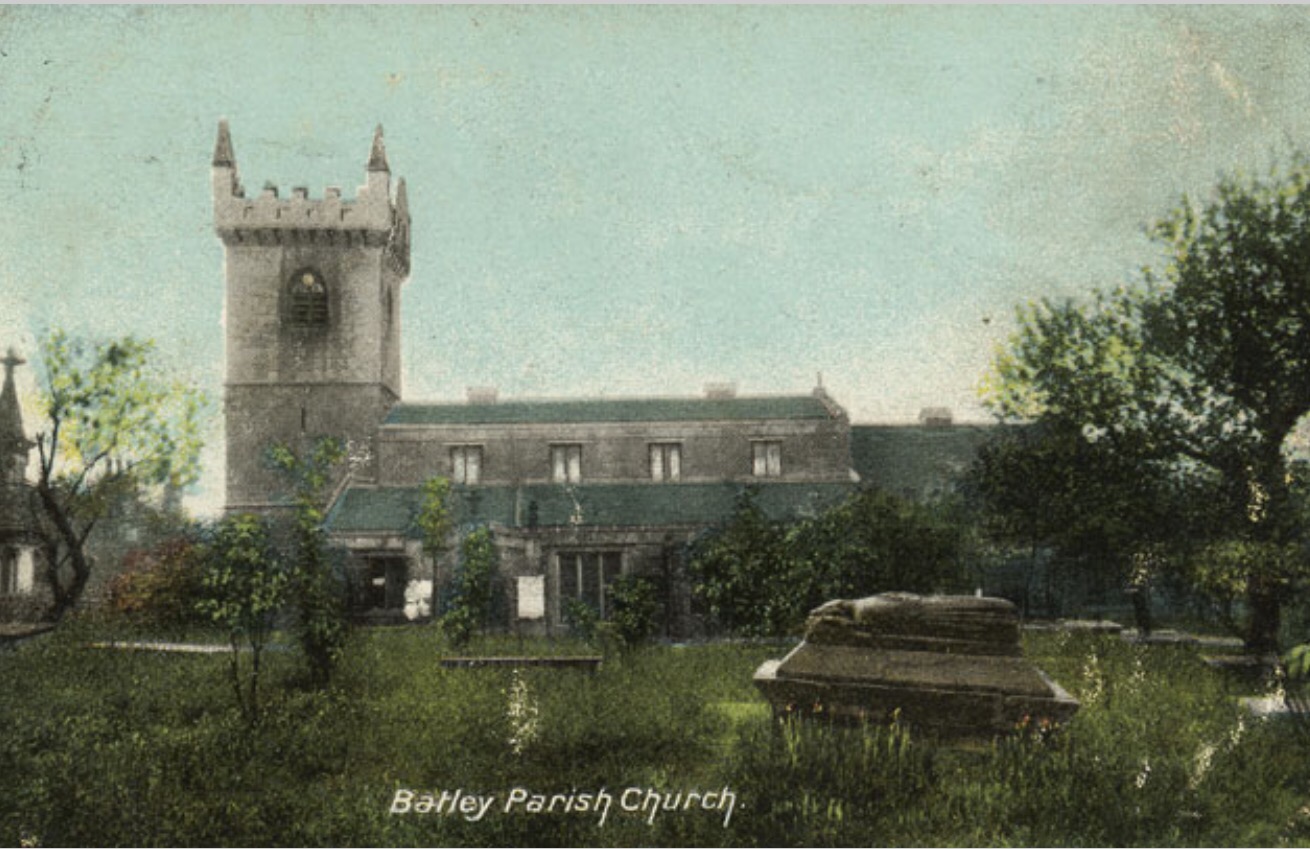

On 18 January 1855, Richard further cemented these powerful local connections when he married widow Rachel Fox at Batley parish church. Five years after the death of her husband David, the 1851 census noted an unusual occupation for her – as a rag dealer employing five girls. Dig deeper, and perhaps it was not totally unexpected. Her husband worked in the woollen trade, and her father, Joseph Jubb, was among Batley’s textile manufacturing royalty. Associated with Hick Lane Mill, founded in 1822, and said to have been the first built for the production of shoddy cloth, Joseph later operated from New Ing Mill. More about a tragedy which took place in connection to his business can be read here.

It seems Robert took over his wife‘s business, as the 1861 census finds the family at Up Lane, Batley, with Robert recorded as a rag merchant employing five women. However, when Batley became a Borough in 1868, Robert was appointed Batley’s first Borough accountant. This is the job recorded for him in the 1871 census.

The stresses of work may have affected Robert, because he was prone to indigestion, popping into William Parrington’s chemist shop on Commercial Street two or three times a week to have a draught of pepsine made up. 23-year-old Benjamin Scatcherd, who had worked for three months as the chemist’s assistant, had of late done this under the supervision of his boss.

At around 6pm on 22 September 1874, just before going to the Town Hall for a Sanitary Committee meeting, Robert called in at the chemists for his usual draught. William Parrington had nipped out, so Ben made it up unsupervised. It comprised of four elements – pepsine, water, bi-carbonate of potash, and compound ammonia. The pepsine dose was around 10 grains, unweighed.

At around 7pm, William Parrington returned and saw an empty glass measure on the counter. Ben told him Mr Shackleton had been in for his draught. Eagle-eyed William then noticed that whilst the pepsine bottle was in the correct place, a morphia bottle was on the wrong shelf. The two bottles were the same size, and morphia and pepsine were similar coloured powders.

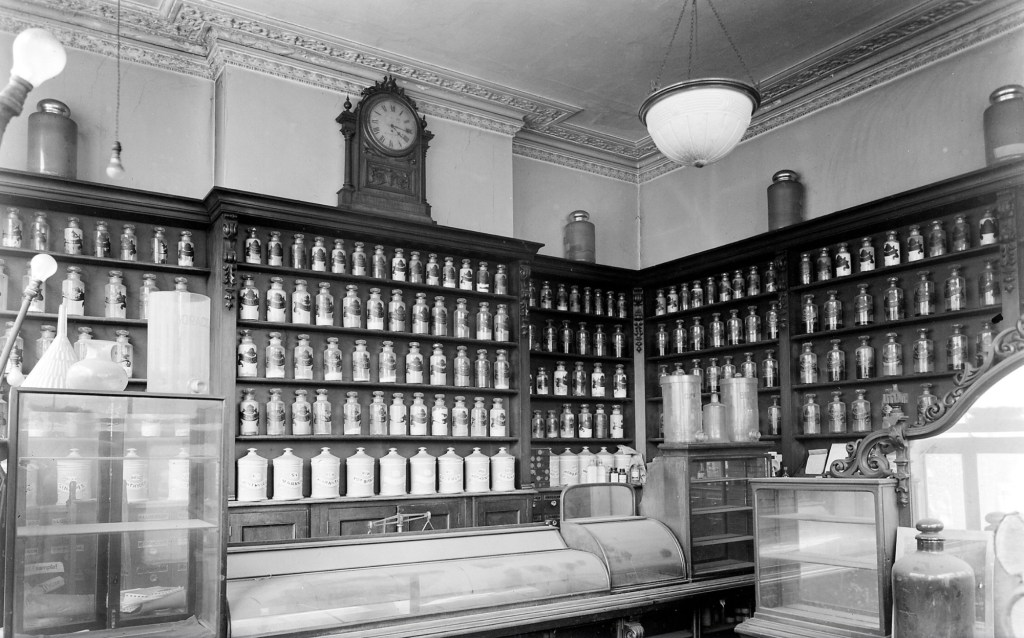

An array of medicine bottles in a late 19th century chemist’s shop Licence: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Credit: Late 19th century Chemist’s shop formerly owned by N.F. Tyler.Wellcome Collection. Source:Wellcome Collection.

William Parrington quickly suspected what had happened, a suspicion which the horrified Ben Scatcherd confirmed. Despite the shop being well-lit and the bottles clearly labelled, his young assistant, distracted by other customers in the shop, had confused the pepsine with morphia. Even worse, 10 grains of morphia was a fatal dose – the normal dose being an eighth of a grain, to a grain!

Hoping to avert disaster, William hot-footed it over to the Town Hall, only to find he was too late – Robert had already taken the draught. In response to the chemist’s enquiry he said he felt “sleepy and drowsy.” William told him about the medicine mix-up, and took the drug-poisoned Borough accountant to his shop where emetics were unsuccessfully administered. No vomiting ensued to dispel the poison.

Ben Scatcherd was dispatched at speed to fetch Drs. Bayldon and Keighley, who gave stronger emetics and applied a stomach pump three times – all to no avail. The potion was not brought up.

Robert’s brother-in-law, Healey warp agent John Thomas Marriott (who happened to be one of the Councillors at the dramatically interrupted meeting), was called to Parrington’s shop at about 9pm. He – along with the chemist – took the stupefied accountant back to Robert’s home on Hanover Street, staying with him through the night. Over the next two days the chemist and doctors were frequent visitors to the Shackleton home. Robert did briefly rally from his comatose state on Wednesday, being able to speak and raise himself up in bed, but it proved temporary. By the evening of Thursday 24 September he once more relapsed, dying at around 10.40pm that night.

His funeral, held on Saturday 26 September 1874, was a major civic display, with the town’s great and good – including its Mayor, Councillors, and an assortment of high-ranking Corporation officials – prominently represented. The five family mourning coaches and several private carriages gave further indication of the status of the deceased.

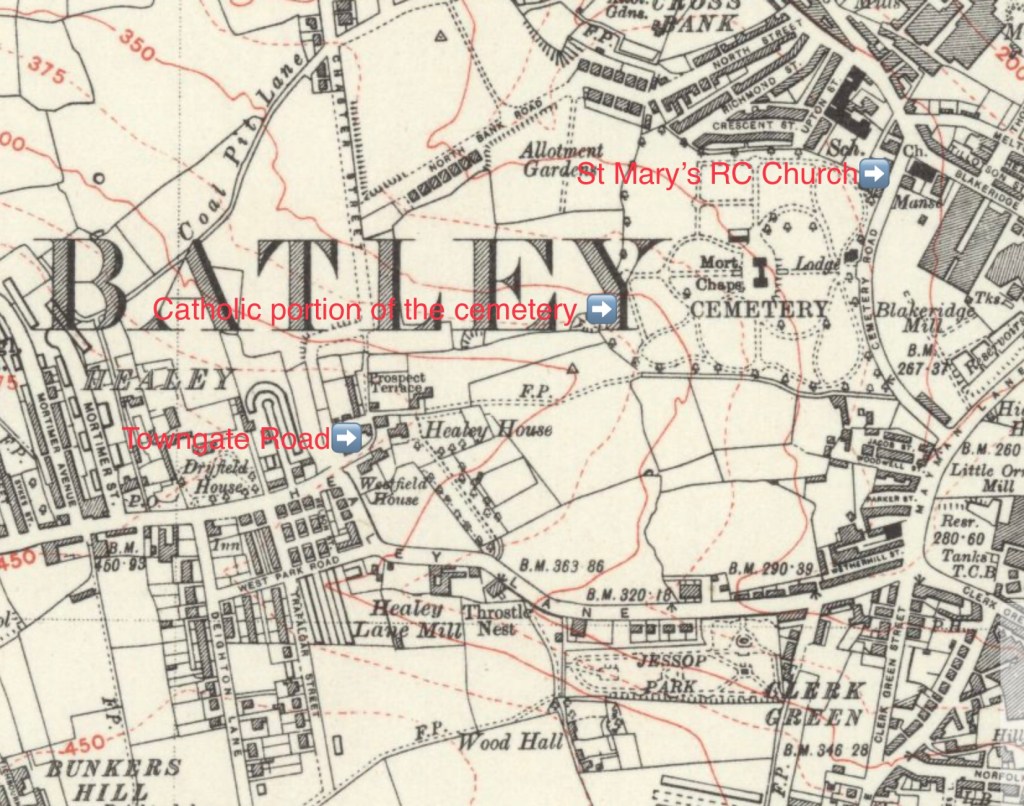

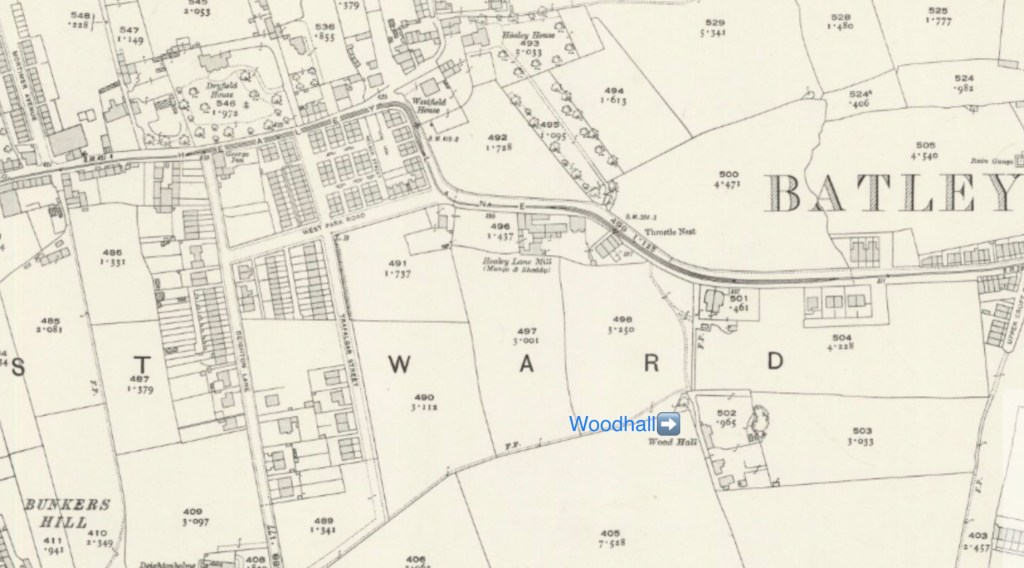

As the cortège made its way from the Shackleton’s Hanover Street home to Batley cemetery, it passed through Batley’s quietened streets, bordered by shuttered shops and blind-drawn houses, and lined by hundreds of townsfolk paying their silent respects.

Whilst great sympathy was expressed with the Shackleton family, this sympathy extended to Ben Scatcherd, the young man whose lapse in concentration led to him administering the fatal dose morphia.

The inquest, held the day before, considered whether Scatcherd had been guilty of criminal negligence. Whilst the foreman indicated the assistant had displayed a degree of carelessness, their unanimous verdict was “Death from misadventure.” The only punishment inflicted on Ben Scatcherd was the heavy burden to his conscience, knowing his error had resulted someone’s death.

Surprisingly, the 1881 census shows Kirkburton-born Scatcherd still working as a druggist’s assistant. He also had a spell as a rag merchant’s book-keeper, before setting up his own business as a stocking knitter and dealer in woollen goods in Batley Carr. His business expanded, and he took on premises in Town Street, becoming a highly respected tradesman in the area. He died in 1917.

Postscript:

I may not be able to thank you personally because of your contact detail confidentiality, but I do want to say how much I appreciate the donations already received to keep this website going. They really and truly do help. Thank you.

The website has always been free to use, and I want to continue this policy in the future. However, it does cost me money to operate – from undertaking the research to website hosting costs. In the current difficult economic climate I do have to regularly consider if I can afford to continue running it as a free resource.

If you have enjoyed reading the various pieces, and would like to make a donation towards keeping the website up and running in its current open access format, it would be very much appreciated.

Please click 👉🏻here👈🏻 to be taken to the PayPal donation link. By making a donation you will be helping to keep the website online and freely available for all.

Thank you.

As a professionally qualified genealogist, if you would like me to undertake any family, local or house history research for you do please get in touch.

More information can be found on my research services page.

Sources:

• Batley Cemetery Burial Register.

• Censuses England and Wales, various dates.

• Coroner’s notes.

• Newspapers – Various.

• Parish Registers – Various.

• Power and Influence, Batley Cemetery Walk – Malcolm Haigh.

• Quaker Records.

• Vivien Tomlinson’s Family History website, https://vivientomlinson.com/batley/index.htm