Sometimes we overlook more recent family history, concentrating on the more distant past. Currently events of 100 years ago are dominating the news, with national commemoration events for Battles such as Jutland and The Somme, to more individual and personal remembrances for the centenary of the death of a family member.

But here I will focus on a more recent conflict, World War II. We are moving towards a time when this too will disappear from living memory. Sadly those in my family with direct knowledge of this tale are long gone.

This post concerns the fate of Albert Edward Hill, or Ned as he was known: My grandad’s cousin.

Finding out the circumstances surrounding death in conflict can be challenging: Which battle; location; precise cause of death; time; even date; and perhaps there is no known burial place. World War II in many ways presents a bigger challenge than its predecessor, with the public availability of records.

However in Ned’s case it’s all fairly straightforward. He is buried locally at St Paul’s churchyard, Hanging Heaton. His death is well documented. It was not caused by some battle injury. It was the result of a totally avoidably, foolishly tragic accident following a night out.

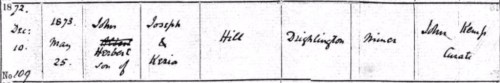

Ned was born on 2 February 1901, one of the seven children of Albert Hill and Sarah Ann Summerscales. These included Harry who died shortly after birth in 1890; Percy, Annie, Lilian, Doris and Arthur.

Ned never married. The 1939 Register, the population list compiled at on 29 September, as a result of the outbreak of war, shows him living at Wood Lane, Hanging Heaton. He is in the household of his brother-in-law Harry Robertshaw along with Harry’s two young sons. Harry’s wife, Ned’s sister Annie died that summer, her burial taking place at St Paul’s Hanging Heaton on 6 July 1939.

In the 1939 Register Ned is recorded as working as a willeyer in a woollen mill. This was someone who operated what was termed a willeying machine. Fibres were fed into this machine, which separated and combed them ready for carding. Newspaper reports at the time of his death, however, indicate prior to his army service he worked as a builder’s labourer, employed by Hanging Heaton-based building contactors George Kilburn and sons.

I do suspect some confusion in the report though, and this occupation possibly applied to his brother Arthur. In the 1939 Register he was a public works contractor’s labourer.

Whatever the true facts are war changed all this, and some two-and-a-half years before his death Ned joined the Army, as a Gunner.

Gunner Hill

His death came entirely out of the blue. Summer 1945, and war in Europe over, Ned returned home to Batley on leave. He finally managed to meet up with his younger brother Arthur, a driver with the RASC, similarly on leave. This was the first time they had seen each other since Ned’s military service. Arthur had been in the Army for four years at this point, serving in Germany, Belgium, France and Holland.

Things must have seemed hopeful. They had survived so far. All being well they would be home soon permanently. The past tragedy of the family would not repeat itself….

Little could they have envisaged that this meeting would be their last, and in three weeks Ned would be dead.

Leave over and Ned returned back to his Unit, the 397 Battery, 122 Heavy Anti-Aircraft Artillery Regiment, stationed at Walberswick, near Southwold in Suffolk. This was part of the network of coastal defences, established in response to the threat of German invasion from May 1940 after their rapid victory in Western Europe. That German threat was now gone.

On 20 July 1945 he and another soldier from the same unit, Gunner Leonard Lomax, had evening leave. They left camp at 6pm that Friday for a night out in Southwold. The ferryman took them over the River Blyth and said he would return for them at 10-30-11.00pm.

An interesting aside is the ferry service from Walberswick had featured in Parliament only weeks earlier on 8 June 1945. There had been a seam steam-driven chain ferry which was discontinued in World War II, and it seems a rowing boat service replaced it. The ferry was privately owned and there had been problems in maintaining a regular service. Suffolk County Council was negotiating to acquire the ferry rights to ensure an adequate service.

Walberswick Ferry circa early 1940s Postcard, F Jenkins, Southwold

Ned and Leonard visited three public houses in Southwold and consumed about six pints of mixed beer. They left town at 10.15pm for the return ferry but there was no sign of the man with the boat. As they were debating whether to return to Southwold to catch the liberty truck to camp, a boat containing two soldiers came from the Walberswick side of the river.

These two soldiers, Lance Bombardier Edward Davis and Bombardier George Rennie were from another Battery. They heard shouts from the Southwold side of the river and thought some men from their Company were stranded as it appeared the ferry service had stopped. Despite having consumed three pints, or maybe because of it, seeing a boat moored in the water they decided to cross to collect their companions, but when they arrived found they were strangers. Nevertheless they offered Ned and Leonard a lift back.

They clambered in the small boat, which turned out to be a yacht’s dingy and using the home-made paddles which were aboard the boat, Edward and George set about rowing back. About halfway across Leonard became aware of his feet feeling wet, water sloshing over the top of his shoes.

George and Edward were now having difficulty controlling the craft and stood up to paddle. They were about eight yards from the Walberswick side when the boat got into trouble with the tide and started to drift back towards Southwold and then seawards. The boat was filling up with water, either the result of a leak or overloading. At this point Ned grabbed a paddle from Edward and the boat turned over throwing all four men into the river.

Leonard and George managed to get hold of a step ladder running down the harbour wall and climb ashore. They could not see the other two men, so made their way to Southwold to inform the police.

Meanwhile Edward, realising that Ned could not swim, tried to keep him up despite not being a strong swimmer himself. He managed to get them both to the concrete wall where Ned grabbed some weeds. Unfortunately they broke away. Edward continued to hold onto Ned but eventually became too exhausted and he had to let him go. Edward then managed to get hold of the ladder and escape.

In summing up the Coroner censured the boat’s occupants. The accident, he said, was the result of four “landlubbers” knowing nothing whatever about boating. The two soldiers should never have taken Leonard and Ned aboard because they overloaded the boat. There must have been some movement with the result that the boat capsized.

He went onto say that he hoped the tragedy would be a warning to others not to take boats without leave, and not to go on a swift running river like this one unless they were experienced persons who know how many a boat would take. “It is difficult to blame anyone because it is pure ignorance” he added.

A verdict of “Death through drowning through the upsetting of a boat” was recorded.

The Commanding Officer of the Battery wrote to Ned’s sister Doris extending his and the Battery’s sympathies as follows:

“On behalf of the ranks of this battery wish to express to you our horror at this tragedy. Gunner Hill was a grand soldier and a man well-known and loved by the men of this unit”.

Ned’s body was brought back to Batley and he was buried in the church yard at St Paul’s, Hanging Heaton, just weeks before VJ Day and the war effectively ending.

Arthur survived the war. But Ned’s fate echoed that of another brother in another conflict, Percy. He died almost 29 years earlier in The Great War, during the Battle of the Somme.

Memories too of the newspaper “Roll of Honour In Memoriam” notices which the Hill family, including the then teenager Ned, placed in the papers all those decades before, mourning the loss of Percy.

Batley News – 5 October 1918

Hill – In sad but loving memory of our dear son and brother, 1736 Sergt Percy Hill, 1st-4th KOYLI (Batley Territorials) who died from wounds at Warloy Baillon, West of Albert, France, September 30th, 1916, aged 24 years.

When last we met, and fondly parted

Our hopes were high, our faith was strong,

We trusted that the separation

Though hard to bear would not be long

We often sit and think of him when we are

all alone

This memory is the only thing we can call

our own;

Like ivy on the withered oak, when other

things decay

Our love for him will ever live, and never

fade away

Ever remembered by his sorrowing mother, father, sisters and brothers, 92, Back Bromley Street, Hanging Heaton

A family which had now lost a brother in both World Wars.

Sources:

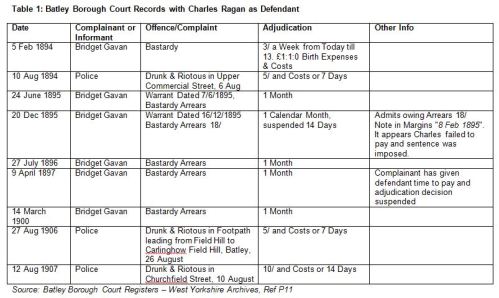

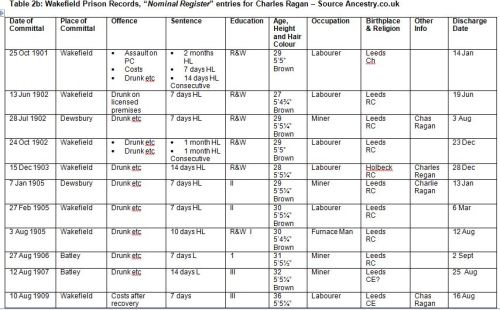

Looking at the censuses with this fresh information, Charles Joseph Ragan, to give him his full name, was born in Holbeck in 1869. He was the son of Irish-born coal miner John Ragan and his wife Sarah Norfolk, a local girl from Hunslet. The couple married in 1866 and by the time of the 1871 census the family was recorded living in Holbeck. Besides Charles other children included six year-old Hannah Norfolk, three year-old Thomas and infant daughter Sarah.

Looking at the censuses with this fresh information, Charles Joseph Ragan, to give him his full name, was born in Holbeck in 1869. He was the son of Irish-born coal miner John Ragan and his wife Sarah Norfolk, a local girl from Hunslet. The couple married in 1866 and by the time of the 1871 census the family was recorded living in Holbeck. Besides Charles other children included six year-old Hannah Norfolk, three year-old Thomas and infant daughter Sarah.