The most common occupation in my family tree is “coal miner”. Unsurprising given my paternal and maternal West Riding roots. As a result I’ve spent quite a bit of time researching the history of coal mining: the social and political aspects as well as the general occupation and its development through time.

This research could form the basis of many posts. The aspect I’m focusing on this time is the perilous nature of the work. “Poldark” brought this to mind. Different type of mining, but the death of Francis highlighted the dangers of underground work in the late 18th century and made me think once again about my coal mining forefathers. However grim I think my job is, I only have to think about my ancestors, men, women and children, who worked down the coal mine to realise how lucky I am.

Even in more recent times coal mining was a hazardous, unhealthy occupation. But in terms of my 18th and 19th century family history, these were days before today’s stringent health and safety regulations. Indeed in the early days of my ancestors the working was totally unregulated.

The cramped, damp conditions and physical exertion led to chronic muscular-skeletal problems and back pain as well as rheumatism and inflammation of the joints. Many suffered from loss of appetite, stomach pains, nausea, vomiting and liver troubles. Most colliers became asthmatic by the time they reached 30, and many had tuberculosis. And all this would have led to days off sick without income to support the family.

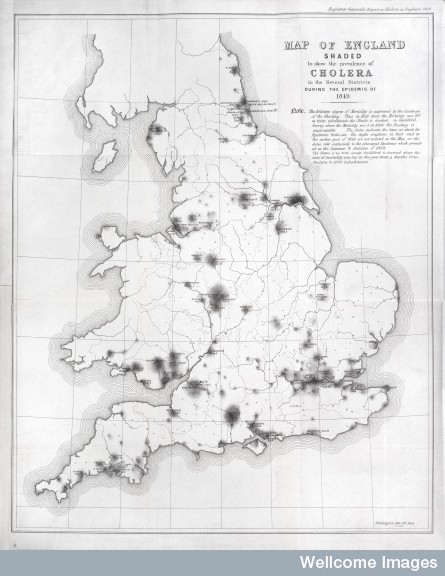

Then there were the accidents. No-one knows how many deaths there were in the first half of the 19th century, let alone earlier. An unreliable estimate in 1834-5 of the number of lives lost in coal mines in the previous 25 years gave the number of deaths in the West Riding as 346 and the evidence is the high proportion were children. According to the appendices of the Mines Inspectors Report’s 1850-1914 some 70,700 miners died or sustained injures in the mines of Great Britain from 1850 to 1908. However even this is not reliable, because the number of non-fatal accidents taking place between 1850-1881 is unknown. It was no-ones job to collect the information.

It is true that miners themselves took risks, failing to set timber supports, propping air doors open and working with candles when it was dangerous to do so even after the invention of the Davy lamp. But colliery officials and managers also cut corners and costs leading to dangerous conditions, for example failing to replace candles with lamps, not supplying sufficient timbers, not ensuring adequate ventilation, using defective colliery shafts which were not bricked or boarded and contained no guide rods, as well as drawing uncaged corves (the small tubs/baskets for carrying hewn coal from the pit face) direct from the pits which resulted in falls of coal and people down the shaft. It was not until 1872 that every mine manager was required to hold a certificate of competence.

Whilst explosions exacted a heavy toll and made headlines, it was the individual deaths and injuries sustained over weeks, months and years by falls of coal and roof which were responsible for most accidents, fatal or otherwise.

One of the earliest mining ancestors I’ve traced is my 6x great grandfather Joseph Womack, born in around 1738. And his is the earliest family mining fatality.

Joseph married Grace Hartley on 11 February 1760 in the parish church of St Mary’s Whitkirk. It is the oldest medieval church in Leeds and a church probably existed on the site at the time of the Domesday Book. The name “Whitkirk” or “Whitechurch” is first recorded in the 12th Century in a charter of Henry de Lacey, founder of Kirkstall Abbey, confirming the land of Newsam, Colton and the “Witechurche” to the Knights Templars. The present building dates from 1448-9 but underwent substantial restoration in 1856. So it is essentially the building in which my 6x great grandparents married.

The man known as the father of civil engineering, John Smeaton, is buried just behind the main altar. Perhaps Smeaton’s most famous work is the 3rd Eddystone Lighthouse, completed in 1759 just the year before Joseph and Grace’s marriage. His other works included the Forth & Clyde Canal, Ramsgate Harbour, Perth Bridge, over 60 mills and more than 10 steam engines.

Joseph signed the register in a wonderfully neat hand. It’s always a thrill when I see the signatures of my ancestors. And especially those who worked in manual jobs not associated with literacy.

The marriage entry indicated Joseph and Grace were both residents of the parish. The location was pinpointed to Halton with the baptism of their first child, Joseph, on 22 October 1760. This location was confirmed in each of their subsequent children’s baptismal entries. Halton was about three miles east of Leeds in Temple Newsam township with Whitkirk parish.

Another son, Richard, was baptised on 27 June 1762 followed by their first daughter Mary, my 5x great grandmother, on 12 February 1765. Four other Womack children’s baptisms are subsequently recorded – William on 21 January 1770; Henry on 24 September 1772; Thomas on 6 August 1775; and Grace on 14 February 1779. This final baptism is more detailed, giving Grace’s date of birth as 31 December 1778 and stating that her father, Joseph, worked as a collier.

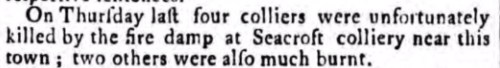

The Womacks, Joseph and his sons, were a coal mining family working at the local Seacroft colliery. Joseph and his eldest sons Joseph and Richard were there one day in May 1781 when tragedy struck in the form of an explosion. The events reached papers nationally as well as locally. The coverage is typified by this paragraph in the “Leeds Intelligencer” of Tuesday 22 May 1781. According to the newspaper the explosion took place on a Thursday, which would make it 17 May. However this may be inaccurate. I will return to this later. Typically for the time no names are given.

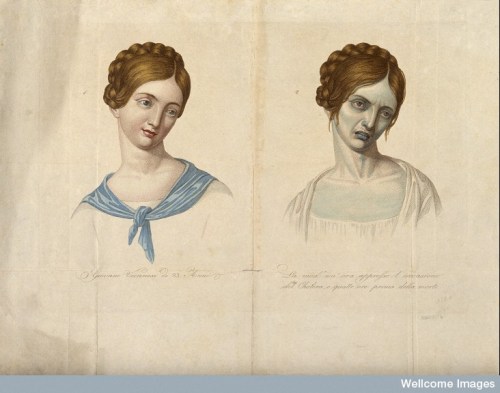

In the era before the 1815 invention of the Davy Lamp, candles were the only form of light in the mine. But the risk of explosions with naked flames from these candles igniting methane gas was high, even in well ventilated pits. Firedamp was the name given to an inflammable gas, whose chief component was methane. This was released from the seam and roof during working. And on this fateful May day the Womack father and sons were caught in its ignition.

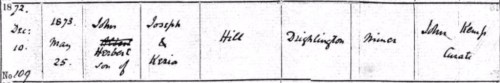

We turn to the Whitkirk burial register for the details of how this newspaper snippet linked to the Womacks. The register gives the following burial details on 18 May 1781:

“Joseph Womack collier slain by the firedamp at Seacroft also his son Richard Womack who was slain at the same time. The father was aged 43 the son 19 years”

Joseph (junior) was one of those hurt in the incident. This is shown by an entry in the same register, dated 2 June 1781: sadly another burial. It is Joseph’s. He lingered for several days before succumbing to his injuries, described as “bruises”. The entry states that his injuries were the result of the same incident in which his father and brother were killed.

Besides being emotionally devastating for the family, with the death of two members on the same day and a third receiving injuries in the same incident leading to his protracted death two weeks later, it would have been economically crippling. The three main breadwinners wiped out in a single stroke. Grace was left to bring up several children – the eldest 16 years old, the youngest just two.

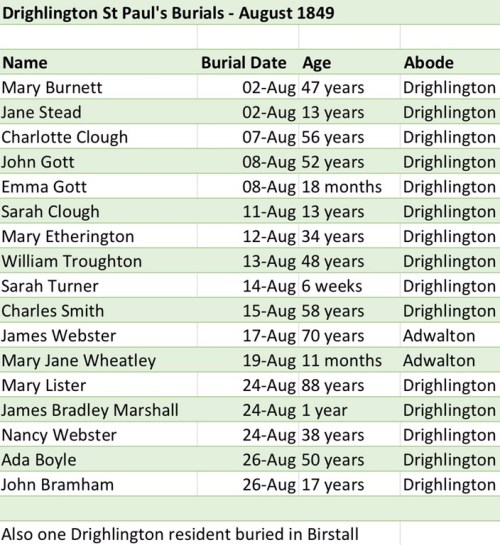

Less than two years after the death of his father and brothers Thomas died, aged eight, as a result of a fever. This is a notoriously vague catch-all description for the period indicating, yet again, that in these times the precise source of illnesses were often not known but which clearly suggests some kind of infection. There are no other clues or hints. Checking the burial register for the period around Thomas’ death reveals nothing, for example an epidemic or outbreak of common illnesses in the area. He was buried on 25 April 1783 in the parish.

Surprisingly the family do not appear in the list of recipients receiving parish dole money. Neither are they mentioned in the parish churchwardens and overseers accounts or vestry minutes, but there is very little poor law related material in these specific Whitkirk documents. It is very possible that they were supported by the parish via this mechanism, but these records have not survived, or else I’ve not yet discovered them in my visit to the Leeds branch of West Yorkshire Archives.

But the two information sources, newspaper and parish register, give an indication of the devastating effect a pit explosion could have on a family at a time when fathers, brothers and sons (and prior to the 1842 Mines Act women plus girls and boys under 10) worked side by side underground.

A sad footnote to this post concerns the anonymity of those killed. In addition to Joseph senior and Richard, there were two others who lost their lives in the immediate aftermath of the explosion, as reported in the “Leeds Intelligencer” 0f 22 May. Given the date of the article, Joseph junior couldn’t have been one. Their names didn’t appear in any reports I found. I do wonder who they were though, these people who worked and died with my ancestors.

There is nothing to indicate any other Whitkirk burials of the period applied to these victims. Parishes adjoining Whitkirk were Leeds, Swillington, Rothwell and Barwick in Elmet. Leeds St Peter’s parish church provides a cause of death for all burial entries for the period. Sadly I drew a blank in this search. Likewise for Swillington St Mary’s and Holy Trinity at Rothwell. However, Barwick in Elmet All Saints register records the burial on 17 May 1781 of 33 year old Christopher Dickinson from Lowmoor. He died on 16 May 1781, “kild in Seacroft coalpitts“. So was this the same incident? If so it indicates the inaccuracy of the newspaper date which implied a 17 May accident date.

Providing the newspaper got the numbers right, the other individual remains a mystery. The only possibility so far is a cryptic and inconclusive 17 May 1781 entry in the nearby parish of Garforth St Mary’s “Thos son of Mathew Limbord colier aged 23 years” No cause of death. And really it’s not clear if it was Thomas or his father who worked as a collier.

The “UK Coal Mining Accidents and Death Index 1700-1950” doesn’t offer a solution either. This was on the now obsolete “Coal Mining History and Resource Centre” website, which I wrote about in my previous post. As indicated in that post, the index is now available on Ancestry.co.uk – but this accident is not recorded. I may never know who the fourth person was. And it makes me think how many other mining deaths are similarly lost.

Sources:

- St Mary’s Whitkirk Parish Register and records

- “Leeds Intelligencer”

- National Coal Mining Museum: http://www.ncm.org.uk

- The North of England Mining Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers: http://www.mininginstitute.org.uk

- The Durham Mining Museum: http://www.dmm.org.uk

- “Voices from the Dark – Women and Children in Yorkshire Coal Mines” – Fiona Lake and Rosemary Preece

- “Working Conditions in Collieries around Huddersfield 1800-1870” – Alan Brooke

- “My Ancestor was a Coalminer” – David Tonks

- “British Coalminers in the 19th Century” – John Benson

- “The Yorkshire Miners: A History – Volume I” – Frank Machin

- “The history of the Yorkshire Miners 1881-1918” – Carolyn Baylies

- “Tracing your Coalmining Ancestors” – Brian A Elliott

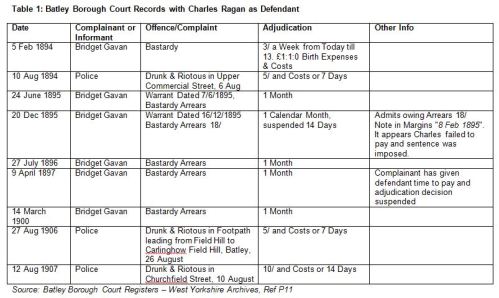

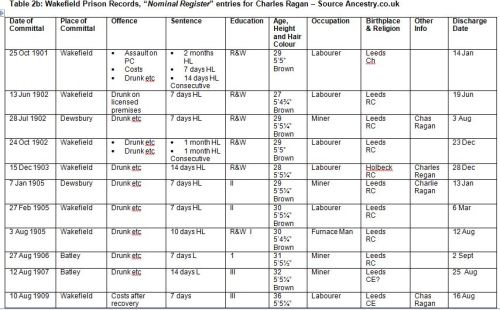

Looking at the censuses with this fresh information, Charles Joseph Ragan, to give him his full name, was born in Holbeck in 1869. He was the son of Irish-born coal miner John Ragan and his wife Sarah Norfolk, a local girl from Hunslet. The couple married in 1866 and by the time of the 1871 census the family was recorded living in Holbeck. Besides Charles other children included six year-old Hannah Norfolk, three year-old Thomas and infant daughter Sarah.

Looking at the censuses with this fresh information, Charles Joseph Ragan, to give him his full name, was born in Holbeck in 1869. He was the son of Irish-born coal miner John Ragan and his wife Sarah Norfolk, a local girl from Hunslet. The couple married in 1866 and by the time of the 1871 census the family was recorded living in Holbeck. Besides Charles other children included six year-old Hannah Norfolk, three year-old Thomas and infant daughter Sarah.