Searching for my ancestors in the Batley library newspapers, I ended up totally side-tracked reading about the goings-on in the town’s New Street area. Some incidents involved distantly connected relations. But the real value was the insight it gave into the community in which my ancestors lived, over a narrow timeframe. I looked at the two years from Christmas 1875. Whilst I didn’t read every paper, the ones I skimmed gave a flavour.

The 1875 Christmas festivities in New Street, an Irish immigrant area, resulted in court appearances for a number of its residents. The first involved Ann Gavan, a married woman (so far no link with my Gavans), accompanied by the headline in the “Batley Reporter” of 1 January 1876 “The Way Christmas is Kept in New Street”. On 27 December she appeared at Batley Borough Court, convicted of being drunk and riotous on Christmas Day.

She attracted police attention on Christmas Eve. Seeing a crowd gathered around her house, Police Sergeant Gamwell looked through the window. He saw her lying heavily drunk on the floor, surrounded by a crowd of boys. Her husband was also drunk. In fact they were seldom sober. By 3am Christmas Day the pair were cursing and swearing, attracting a large crowd. At this point Police Constable Shewan apprehended Ann. He couldn’t manage her husband too.

But this wasn’t an isolated New Street incident. Appearing in Batley Borough Court on the same day were an assortment of individuals. Christmas Day saw John King, described as an old man – although what constituted old then may not be the case by today’s standards, hauled off to the police station. Again the charge was one of drunk and riotous behaviour. He also assaulted the arresting office, Police Constable Beecroft. On 26 December Patrick Jordan and Patrick Moran’s drunken fight resulted in a drunk and riotous conviction for the pair. Their escapade tied up five or six police officers most of the evening. And Michael McManus was similarly convicted, for the 17th time.

That wasn’t the end of the parade of individuals before Batley Borough Court for events that Christmas in New Street. The following week’s edition of the “Batley Reporter” contained a string of obscene language cases: Mary Foley used obscene language towards several policemen on 26 December; Ellen Tarpey was convicted of using obscene language toward Mary Gavan (a potential family connection here) on 27 December; the case against John Hannan (another family link) was dismissed. He faced a charge of using obscene language towards Ann McCormick on 28 December. And finally yet another case involving Ann McCormick as victim, this time at the receiving end from John McManus on 27 December. The Mayor wished the bench could fine her too, as he considered her equally to blame in the incident.

The idea that this was a one-off string of cases occasioned by Christmas doesn’t hold water. True the police office was nearby, so the area fell under particular scrutiny. But no other area of Batley had such a high proportion of cases. In fact the Mayor “….commented strongly on the number of cases of obscene language brought before the Bench especially from that locality; and said if it was not for the cases from that district the magistrates would have little to do”.

And going through the papers there are more cases, not confined to holidays. The one incident that stuck out for me did involve distant relatives: John Hannan, of the murderous poker assault episode on his father-in-law, and his wife, Margaret. The newspaper heading reads “Dealing Gently With New Street Rioters”.

The incident started at 3.45pm on Sunday 15 October 1876, lasted two or three hours, and involved several residents. It was sparked by the disputed use of a privy in the yard of Patrick Gannon. Hannan and another man broke open its door. They claimed they had a right to be in the toilet. It appears Gannon and nearby neighbour Mary McManus, with whom the Hannans now lodged, shared the same landlord. The landlord authorised Mary’s use of the privy.

Outside Toilet at Beamish – Wikimedia Commons by Immanuel Giel

Gannon claimed that as he challenged the “

intruders”, Hannan struck him. At this point Gannon fetched the police.

Normally in these circumstances the police would not attend. They would issue an assault summons. On this occasion Police Constable Friendly Hague went with Gannon to New Street, an action subsequently criticised. He defended it by saying Gannon was afraid to go home. Perhaps the fact Hannan was well-known to the police had an influence.

It was claimed Hannan re-commenced his attack on Gannon. Police Constable Webber, upon seeing the crowd gathered in New Street, went to see what was happening. He assisted Police Constable Hague in apprehending Hannan, who resisted. In the ensuing melee Bridget Gannon, wife of Patrick, came out with a poker. At this point Hannan was on the floor, black in the face from being throttled by Police Constable Hague.

Margaret Hannan now joined in to rescue her husband. She too was armed with a poker, striking both Gannon and Police Constable Hague about the head, shoulders and back with it, saying “I’ll not let the b___ take him”. She was led away by Mary McManus.

Michael Gallagher also joined the affray, kicking Police Constable Hague whilst on the floor, saying “We’ll kill the b___ if you like”. Hannan incited Gallagher further by crying “Go into him”, so Gallagher obliged, aiming another kick.

The upshot of this Court appearance before the Mayor, Alderman J.T.Marriott: Hannan was cleared of assaulting Gannon. He was also cleared of damaging Police Constable Hague’s trousers, as the Mayor said the policeman should not have rushed in as he did. He was, however, convicted of the assault on Hague; as was Gallagher; Margaret was convicted of assaulting both the policeman and Gannon.

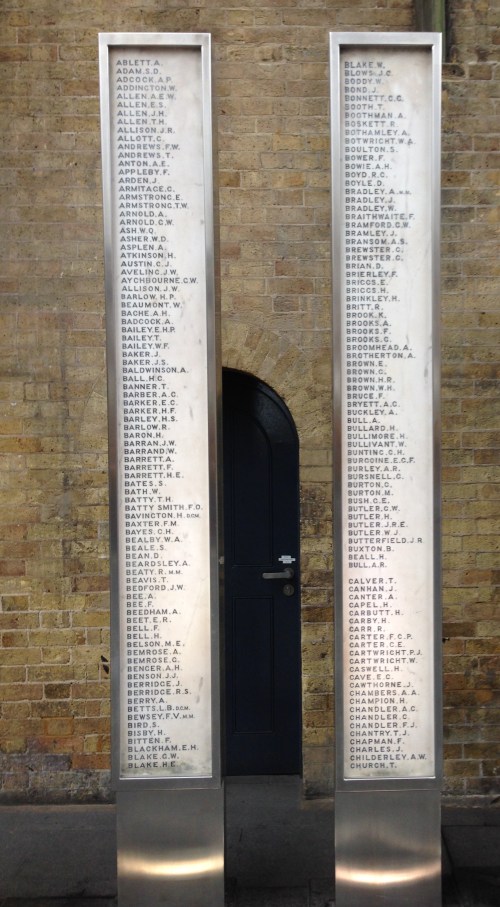

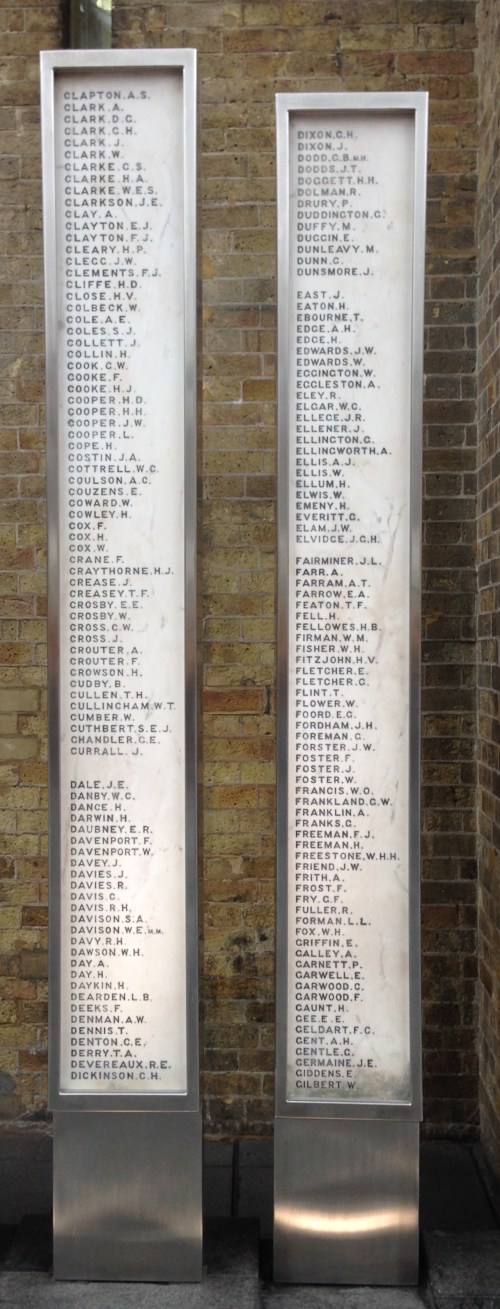

Whist on the surface this seems a series of humorous incidents, it highlights the problems faced by these early Victorian police in executing their duty. It was also a precursor to an event with far more serious consequences: the death of a policeman in the town on 9 December 1877. Inevitably New Street featured in the events.

William Peet [1] was born in January 1853, the son of agricultural labourer Thomas Peet and his wife Sarah. His baptism took place on 1 May 1853 in the parish of Wolvey in Warwickshire, close to the border with Leicestershire. The family are recorded here prior to William’s birth in the 1851 census, with daughters Sarah Ann (6), Elizabeth (2) and Jane (2 months).

By the time of the 1861 census the Peets had moved north to Broomhill near Barnsley. In addition to William and his parents, the family included Jane (10), Joseph (6) and infant son Thomas.

William’s father died sometime prior to the 1871 census. This census shows William as the oldest child residing in his mother Sarah’s home. Not yet 50 and described as an annuitant, she had five other sons at home, three under the age of 10. These were Joseph (16), Thomas (10), Fred (8), John (7) and Harry (4). William’s wage from his job as a mason’s labourer must have been a welcome support.

In September 1874 William married 19 year old Mary Downs at Wombwell parish church. The register entry describes his occupation as a miner. Two daughters followed, Lily (1875) and Sarah Ann (1877).

It was shortly after Sarah Ann’s birth that William undertook a significant change of career. 1856 saw the creation of the West Riding Constabulary, an organisation which William joined on 17 September 1877. The Examination Book shows he measured 5”8¼”, had light hair, light blue eyes and a fair complexion. He described his trade as a labourer, his previous employment being at Barnsley’s Lundhill colliery. He was attached to the Division responsible for policing in Batley on 23 October 1877.

It was at around the time of a sequence of serious incidents between Batley’s Irish community and the police. In one incident, originating in New Street at the end of November 1877, Police Constable Beecroft suffered such a serious assault it rendered him unfit for work weeks later. This was the situation facing the new policeman. A situation which cost him his life on Sunday 9 December 1877.

The remarks column of his Examination Book reads:

“Killed in a street row at Batley by a number of drunken Irishmen (between 11pm and midnight). He and PC 278 Herring were quelling the disturbance when 7 or 8 Irishmen turned round and began to beat, stone and kick them in a most unmerciful manner, one of them striking a fatal blow on the head with a heavy walking stick taken from PC Herring”.

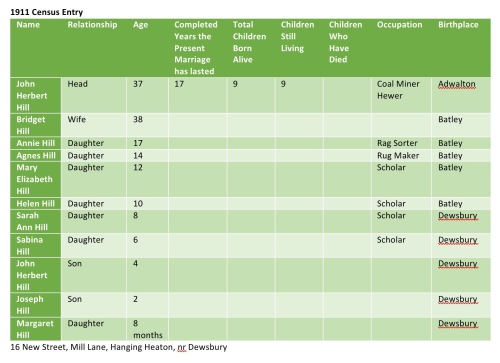

From around 9pm on 8 December PC Peet and PC Robert Herring patrolled the Batley area around New Street, Wellington Street, Hick Lane and Union Street. At just gone 11pm they heard a disturbance on Cobden Street and witnessed a crowd of around 60 men and women. A number of them, William Flynn (27 year old shoemaker), Patrick Phillips (labourer, age 25 ), John Ryan (labourer, 24) and Michael O’Neill (labourer) had been to a jig at Patrick McGowan’s “Prince of Wales” beerhouse in Cobden Street. New Street’s Ann McCormick, a rag picker and a familiar name in my research of the area, (there was a mother and daughter of this name and I suspect this was the daughter whereas the one involved in the Christmas 1875 incidents was the mother), also attended the dance. Now, after closing time, many of the revellers became involved in a street dispute.

Some men had their coats off, including Flynn, O’Neill and Phillips, and were threatening to strike men from the Staincliffe area and neighbouring town of Heckmondwike, including Patrick Hunt. When PCs Peet and Herring arrived Ann McCormick, screaming and crying, claimed she had been struck by one of the Batley men, pointing in the direction of Flynn and O’Neill. Apparently it was the latter. There is the possibility she was trying to obtain payback for a prevented marriage.

1892 map showing the area events took place

The police tried to diffuse the situation, attempting to get the crowd to disperse. At this point the Staincliffe and Heckmondwike men made their escape. Flynn and his mates progressed down Peel Street, swearing and cursing but then, reaching Wellington Street, refused to move.

Challenged by Herring about their dispersal delay, one of the men knocked the policeman down stealing his wooden stick. He then charged at PC Peet striking him about the head with the stolen weapon, knocking him to the ground and taking his truncheon.

There was some confusion as to the identity of this assailant. PC Herring remained adamant throughout the judicial process it was Flynn; but it was a dark night with little lamplight, and evidence from others was confusing with some indicating O’Neill. Some giving evidence claimed not to have seen blows struck, others only fist blows. Doubt was also cast on Herring’s identification because he had only been working in the Batley area for a few weeks. And new witnesses crawled out of the woodwork disputing events. For example Mary Foley appeared at the Assizes claiming she witnessed the row but hadn’t appeared before the magistrates earlier in proceedings because she “had a queer husband, a large family, and did not want to be mixed up with the police”.

Whilst Peet was down, Flynn, O’Neill and Ryan aimed kicks at him. They then turned on PC Herring.

This provided an opportunity for PC Peet to regain his feet and assist his colleague. The pair managed to grab hold of Flynn. Other men in the crowd began to pelt the police with stones and loose setts which had been left in he street by council workmen carrying out repairs. John McManus, a 25 year old collier, was identified as the man who threw the setts. Phillips as a stone-thrower. Peet was hit on the back of the arm or shoulder. The stone-throwing enabled Flynn to escape into a house in New Street, the police giving chase.

No other officer heard PC Herring’s whistle-blowing calls for help and the crowd refused to assist, so he remained watching the house whilst PC Peet brought police reinforcements. The extra police arrived but upon entering the house they found Flynn had vanished.

The police now went about tracing and arresting those involved. These included Flynn (apprehended in his bed at his Ward’s Hill home 1.30am. His wife woke him and he struck her saying “You b*****”, and to Robert Webber, one of the arresting policemen “It’s thy b***** phizog is it?”). Others rounded up were McManus, Ryan, Martin Devanagh and Patrick and James Phillips. Patrick Phillips, according to some reports, lodged in John Hannan’s house, but the Clark Green[2] location does raise questions as to whether it is “my” man. One person though evaded capture – O’Neill.

Whilst this was going on, at just before 1am in the morning Peet complained of feeling ill and returned to his Purlwell Lane home in the Mount Pleasant area of town. It was a house which he and his family shared with the Herring family. During the early hours he became increasingly unwell, lapsing into a coma. Police surgeon James Cameron was called at around 6am and Peet died just before 8am.

Cameron undertook a post-mortem, assisted by Dr William Bayldon. It revealed Peet had suffered a skull fracture and haemorrhage, causing his death. Peet’s body was taken back to his home near Barnsley for burial.

The two-part inquest in front of Thomas Taylor, district coroner, was held on the 11 and 18 December at the New Inn at Clark Green in Batley. A verdict of murder by Flynn was reached.

The men next appeared before the Magistrates, and a large crowd, at Batley Town Hall on 20 December. The case against Devanagh was dropped as the evidence against him was not sufficiently strong. Herring couldn’t swear to his presence and he, naturally, denied having been there.

At the end of the hearing James Phillips was also discharged. Although said to be at the row, he wasn’t seen doing anything termed fatal.

That left Flynn, Ryan, McManus and Patrick Phillips committed to trial at the Yorkshire Winter Assizes on a wilful murder charge: Flynn as the man who inflicted the fatal blow, the others for aiding and abetting. Some discussion did take place about extending this serious charge wider than Flynn, but the balance of opinion swayed in favour of it. They concluded it was not necessary that all persons should inflict the fatal blow. If those present aided and abetted, they were all equally guilty of wilful murder.

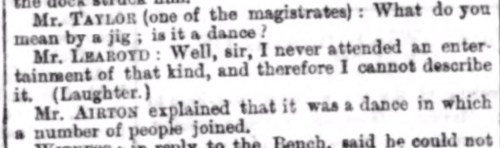

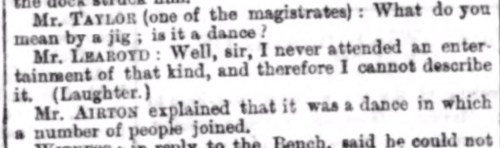

The proceedings in Batley were not without occasional humour, a kind of “us and them” scenario reminiscent of Sir Jeremiah Harman’s Springsteen, Gascoigne and Oasis comments. These included an exchange in Batley Borough Court about the meaning of “jig“, with Mr Airton from the West Riding Police providing the explanation.

“Dewsbury Reporter” 22 December 1877 – A Jig Explained

At the inquest Ellen Chappell, a witness, illustrates wonderfully why we have variations in ancestral surname spellings.

Surname Confusion – “Huddersfield Chronicle” 19 December 1877

The Assizes took place at Leeds Town Hall the following month. One of the first decisions made by the Grand Jury was a downgrading of the charges against Ryan, McManus and Phillips as there did not appear to be any common purpose between Flynn and the others to attack Peet. They now faced a charge of assaulting a policeman in the execution of his duty. Only Flynn faced the charge of wilful murder.

His trial took place on 18 January 1878. To an outbreak of applause in the court the jury returned a “not guilty” verdict. This on the basis of uncertainty as to who stuck the fatal blow – they could not definitely say it was Flynn. He was detained to face an assault charge with the others, the following day.

This was the final trial of the Assizes. Because Flynn had been acquitted of Peet’s murder, no evidence was offered for the assault and he was discharged. Guilty verdicts were reached against the other three men, who each received six month sentences.

Mary Peet and her children returned to her hometown of Wombwell, near Barnsley. The Police Committee granted her a £65 gratuity. A subscription fund was also established for her. She married coalminer Den(n)is Bretton in 1879, having a number of other children during her second marriage, including a son named William.

Besides a man loosing his life, the death of PC Peet highlighted racial tension in Batley, between the Irish and local communities. A series of local newspaper letters and articles are testimony to this. One letter illustrating the fact, which attracted much attention, appeared in the “Dewsbury Reporter” of 15 December 1877. It was written from “A Batley Lad”. It harked back to the leniency shown to those New Street privy rioters amongst others. It read:

“The murder of a constable, often predicted, in Batley, has at last taken place, and perhaps the Irish now will be a trifle more quiet. They have felled many a policeman during the last two years, and when brought up, especially when Mr J.T. Marriott was Mayor and Ex-Mayor, have been let off, as your paper recorded from time to time, with most inadequate punishment. The Irish in this quarter are a very low lot, and rows and fights have taken place every weekend, but instead of the magistracy supporting the representatives of the law they have leaned to the other, and not virtuous side.

I think it is time that we had our own borough police, for if we had I think we should not allow them to be knocked about by the Irish roughshod as the poor county constables have been.

Perhaps the Irish after this murder will remember Patrick Reid”.[3]

Rev. Canon Gordon, the priest at St Mary of the Angels RC Church, referred to the incident in his sermon on Sunday 16 December 1877. He stated the Irishmen involved in the disturbance and murder never entered Church, and were Catholics in name only. He went on to say the event was a disgrace to all true Irishmen and Catholics. The incident confirmed his previously expressed opinion that a murder would be committed in Batley as a result of the excessive drinking which prevailed in the Irish classes. He concluded by expressing the hope that God would severely punish the guilty as a lesson to future generations.

This was the community in which my Irish ancestors lived and were part of. Its history forms a critical backdrop in shaping their everyday lives.

I’ve named only a fraction of those involved in the various stages of the trial for the murder of William Peet. If anyone believes their ancestor is involved I’m happy to check my notes.

Footnotes:

[1] Sometimes referred to as Peete

[2] Modern spelling is Clerk Green

[3] Patrick Reid was an Irish hawker executed in York on 8 January 1848 for the triple murder in Mirfield of James and Ann Wraith and their servant Caroline Ellis

Sources:

- Ancestry.co.uk – Warwickshire Anglican Registers for the Parish of Wolvey; West Riding Constabulary Examination Books; Wakefield Charities Coroners Notebooks, 1852-1909; Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 (HO 27);

- “Batley Reporter” newspaper

- Census: 1851-1881

- FindMyPast – Doncaster Archives Yorkshire Marriages; newspapers including “Dewsbury Reporter”, “Huddersfield Chronicle”, “Leeds Mercury”, “Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer”,

- GRO Indexes

- Wikimedia Commons for photograph of outside toilet, by Immanuel Giel – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1110467