16 December 1914 marked a momentous day for my family. My grandma celebrated her sixth birthday. But not any old ordinary birthday in Batley for her, spent with her mum, dad and seven year old sister Nellie. This birthday was unlike any other.

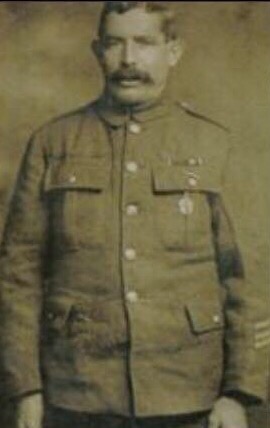

Astonishingly, I discovered this of all days was the day her 46 year-old father, my great-grandfather Patrick Cassidy, chose to enlist with the local regiment, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI). Patrick, born in 1868 in Hagfield, County Mayo, even knocked several years off his age to ensure he would be accepted. His attestation papers show he claimed to be 35 years and 11 months.

I knew my great-grandfather had been in the Army. My grandma told a tale of a motor vehicle turning up at their Hume Street home containing someone to see her dad. The story goes that the officer inside was the one he’d acted as batman for. I had no date for this event, but given my grandma remembered it, I’d guessed in sometime after 1912.

However, because of his age, I’d discounted him seeing his military service during the Great War. Combined with his age, his uniform in one of the family photos, with its three point-up chevrons on the lower left sleeve indicating 12 years good conduct, indicated pre-war service. I’d marked it as pre-1904, as he’d first turned up in Batley in January of that year. And by then he was a labourer. That was also his occupation when he married Ann Loftus in 1906. And also in the 1911 census.

Patrick Cassidy

Patrick CassidyAs it happens his attestation papers backed up this earlier service theory. He confirmed to the attesting officer he had previous time-expired service with the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (West Riding). He described it as 33rd and 76th West Riding, harking back to 1881 and the Cardwell Reforms when the Halifax depot 33rd and 76th Regiments of Foot merged.

One thing I found amusing from these papers: My grandma, who adored her father, always gave the impression of him being a tall man. According to his army forms he stood at the incredible height of…….5’ 3.5”. Just goes to show, don’t take all oral family history as gospel!

Anyway, back to the lie over his age. As an ex-soldier, by this stage of the war, the age limit was 45, not 38 as for other volunteers. So he really did go overboard with his age reduction. In fact, with his precise 35 years and 11 months, it seemed he was still working to the end of August 1914 rule change for volunteers without previous service, when the upper age limit was increased from 30 to 35. He really was determined to do his bit.

Still, I couldn’t get my head round it. Not the fact he chose to sign up. Not even the fact he lied about his age to do so. But why on earth would he do it on his young daughter’s birthday? Why not wait till a few days later? In fact, why not wait till after Christmas? Had there been some major family row that prompted it? Or had a close family member or friend, as yet unidentified by me, died whilst serving? Was my great grandfather out to avenge their death? Those were the only explanations I could come up with.

His papers offered no clues whatsoever as to why he would act in this way and leave his wife, children and labouring job in Batley to take this huge risk. Or did they?

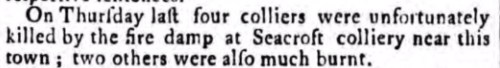

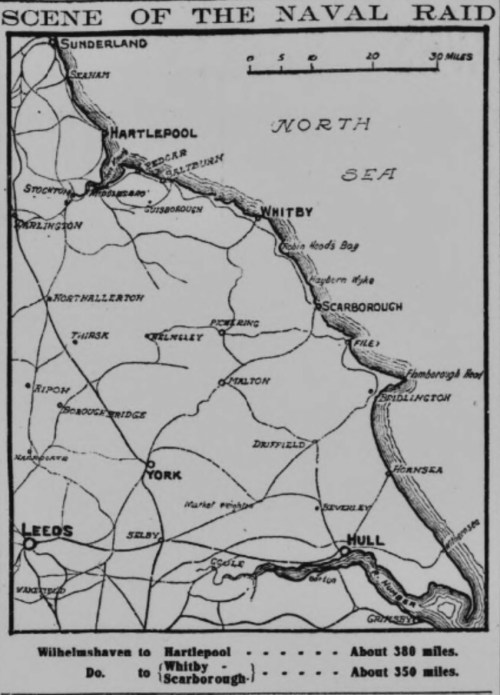

Several months later, whilst doing some general research, I realised the papers did contain the answer. The key was in the date. I’d been looking at it in narrow family terms, my grandma’s birthday. I’d not looked at any wider historical events. Besides being my grandma’s sixth birthday, Wednesday the 16 December 1914 marked the day German Imperial Navy ships Seydiltz, Moltke, Blücher, Derfflinger and Von Der Tann bombarded the east coast towns of Scarborough, Whitby and Hartlepool with a final toll of over 130 killed and almost 600 injured.

The attacks occurred from around 8am to 9.30am that morning. In the immediate aftermath, in scenes reminiscent of Belgium and France, refugees fled their homes seeking safety inland. Distressed residents from the stricken towns, some still in slippers and nightdresses, disembarked in local railway stations with tales of terror and destruction and reports of “scarcely a building left standing.” The historic landmarks of Whitby Abbey and Scarborough Castle suffered damage. Famous seaside hotels, like Scarborough’s Grand Hotel, bore shell scars.

The Grand Hotel, Scarborough

The Grand Hotel, ScarboroughFrom 16 December onwards newspapers the length and breadth of the country carried the stories of this exodus, along with tales of death, injury and destruction wreaked. This from “The Yorkshire Evening Post” of 16 December reporting of arrivals in Leeds at 11 o’clock “One woman who arrived was wearing her bedroom slippers; in her arms was a two-year-old son in her nightdress and an outer garment lent by someone on the train.”

Another refugee was Mrs Knaggs, who lived in the vicinity of Scarborough’s damaged Grand Hotel. She arrived in Leeds on the 1 o’clock train into Leeds with her eight-year-old daughter and a few hastily packed groceries. She recalled meeting “…scores of women and children. All seemed unconsciously making for the railway station. Some were half dressed, and carried with them all manner of household articles. Another refugee had a child of a fortnight old in her arms, and with her was another partly-dressed girl of fourteen…..The streets of Scarborough were filled with women. These refugees were without food, money and very scantily clothed.”

Whitby resident Mrs Hogg was another Leeds arrival. Her house was struck by a shell. She recounted: “Outside shells were flying about, tearing up the pavement and damaging houses….In the fields in the outskirts of town big holes were torn in the ground and all the telegraph wires were down. People were hurrying along, some with a few belongings they had managed to get together. One man was carrying a parrot and two bird-cages. My little boy had run out of the house in his slippers. He lost his slippers on the way, and had to walk in his stocking feet.”

The German navy were dubbed the baby-killers of Scarborough, a reference to one of the victims, 14 month old John Shields Ryalls. In a letter to the Mayor of Scarborough on 20 December 1914 Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty wrote: “Whatever fears of arms the German Navy hereafter perform, the stigma of ‘Baby-Killers of Scarborough’ will brand its officers and men while sailors sail the seas.”

Baby Ryall’s picture along with another victim, 15 year-old boy scout George Harland Taylor, featured prominently in the press with inflammatory headings like “Slain by Germans” and “Killed by the Raiders.” Others included 28 year-old Miss Ada Crow, due to be married to her army fiancé, Sergeant G.R. Sturdy, on what turned out to be the day of her funeral.

Some were of the opinion that the attack was the best thing that could have happened – it would give a boost to recruitment, now waning after the initial rush following the declaration of war. Battalions would be filled on the back of the attack.By 18 December newspapers were reporting a material increase in numbers coming forward to recruiting offices, particularly in the areas affected by the bombardment. And from 18 December a new recruitment poster made its appearance:

AVENGE SCARBOROUGH

Up and at ‘em now!

The wholesale murder of innocent women and children demands vengeance.

Men of England, the innocent victims of German brutality call upon you to avenge them. Show the German barbarians that Britain’s shores cannot be bombarded with impunity. Duty calls you now.

Go to-day to the nearest recruiting depot and offer your services for your King, home, and country.

This theme was echoed in subsequent recruitment poster campaigns. This included a depiction of the ruins of 2 Wykeham Street, Scarborough where four died: Johanna Bennett (58), her son Albert Featherstone Bennett (22) a driver in the RFA, and two young boys John Christopher Ward (9 according to newspapers, although GRO entry gives his age as 10) and George James Barnes (5).

My great-grandfather didn’t wait for these rallying call to arms. He went to the recruiting office on the very day of the attack. Maybe the White Lee picric acid explosion with rumours of German sabotage only a fortnight earlier, which caused death and devastation to Heckmondwike and Batley, also played a part in his thinking. Though I can’t be 100 percent sure, it looks like he enlisted because he wanted to protect his family. The bombardment of east coast town, with the huge loss of life and the streams of refugees which followed, brought the war so much closer to home. The Yorkshire seaside resorts of Whitby and Scarborough were particularly popular local holiday destinations. In fact when war was declared only four months earlier the local Territorials, 1/4th KOYLI, were on their summer camp in Whitby. No longer was it a distant war affecting civilians – women and children – in foreign lands. It was now in Yorkshire. His family were now under threat. He couldn’t stand aside any longer.So what became of him? The attestation papers indicated his resurrected army career with the KOYLI proved short-lived. On 15 January 1915 he was discharged as unlikely to become an efficient soldier. Unsurprising given his age. But the discharge setback did not deter him. It wasn’t the end of his military service.

By pure chance I found an entry in the “Batley Reporter and Guardian” of 27 August 1915. Private Patrick Cassidy of Hume Street appeared in Batley Borough Court charged with being absent without leave from the 3/4th battalion Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, who were stationed at Halifax. So he’d gone back to his old regiment. The Batley Borough Court records gave the offence date as 24 Aug 1915. He pleaded guilty and was remanded to await a military escort. I wonder if this has any link to the vehicle my grandma recalled?

The 3/4th Duke of Wellington’s was formed in March 1915 so it seems Patrick may have remained a civilian for as little as a couple of months after leaving the KOYLI. The battalion remained in England throughout the war, stationed at Clipstone Camp, Rugeley Camp, Bromeswell (Woodbridge) and Southend, training and supplying drafts for overseas service. I’ve traced no Medal Index Card for Patrick so it seems he remained on home shores. However he did see the war out. In the Batley Electoral Register of 1918 he is listed as being absent as a naval or military voter. Unfortunately the detailed Absent Voter List for Batley does not appear to have survived. This would potentially have confirmed his service number and regiment.

So this tale goes to show that when researching family history you need to look at wider historical events be it local, national or international. They too have an impact on the lives and decisions made by ancestors and can help you see your family history in a new light.

Sources:

- Batley Borough Court Records – West Yorkshire Archives

- Batley Register of Electors – 1918

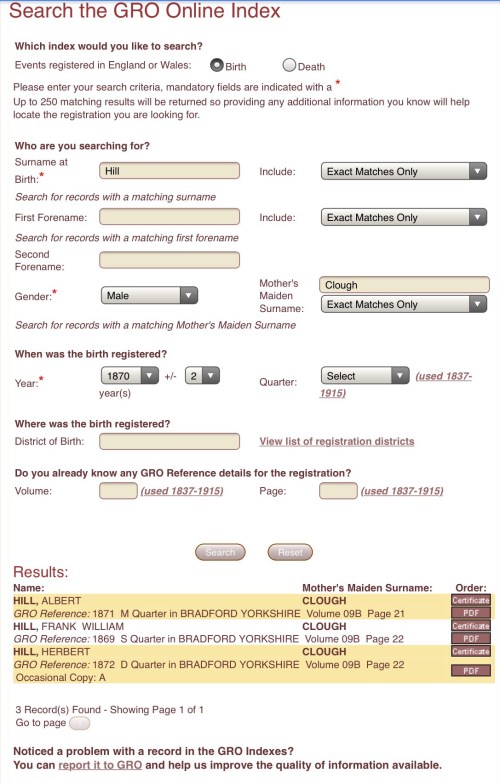

- GRO Indexes

- Imperial War Museum Poster from 1915: “Men of Britain! Will You Stand This?” © IWM (Art.IWM PST 5119). Shared and re-used under the terms of the IWM Non Commercial Licence

- Newspapers including:

- Batley Reporter and Guardian – 27 August 1915.

- Leeds Mercury – 17 December 1914

- Yorkshire Evening Post – 16 and 18 December 1914

- The Leeds Mercury – 21 December 1914

- WO 364 -Soldiers’ Documents from Pension Claims, First World War