Some of you may be aware of the difficulties I have encountered in trying to obtain my uncle’s service records. They are now held at The National Archives, and I applied for them last year. My request was turned down, and in October 2023 I challenged the decision. Others, (you know who you are), also sent letters in support of my challenge.

Although my uncle was killed whilst serving with the Army in the 1950s, because he was born between 1909 and 1939, The National Archives said I had provided no proof of death under the FOI rules. The proof required was either his death certificate, a published obituary, or war dead records (with the online application link directing you to the CWGC database roll of honour). Without this evidence his files were protected until 115 years after his birth (circa 2051 in his case).

I found the rejection quite upsetting given my uncle was killed whilst serving in the Army – something which if his records were examined would be crystal clear. I have now been told because The National Archives are in the process of receiving over 10 million service records, some of which are stored off-site, the records are not called up to check the details within them. They rely on a limited database to do the check, and this database information does not contain if the individual’s death was whilst serving.

However, given the specifics of my access request – that it applied to someone killed whilst serving in the Armed Forces – I believed it was the ultimate insult to be asked to provide additional proof in the form of a death certificate, when the evidence was already held by the government. To be clear, I don’t object to providing a death certificate under normal circumstances. I did so for my dad’s records. But I do object to providing a death certificate for someone who died whilst on military service, whose death was as a direct result of that service, whose death registration was undertaken by the military (not the family, who never received his death certificate), whose overseas burial was with full military honours, and who even has a military headstone. But this death certificate now seemed to be my only access route.

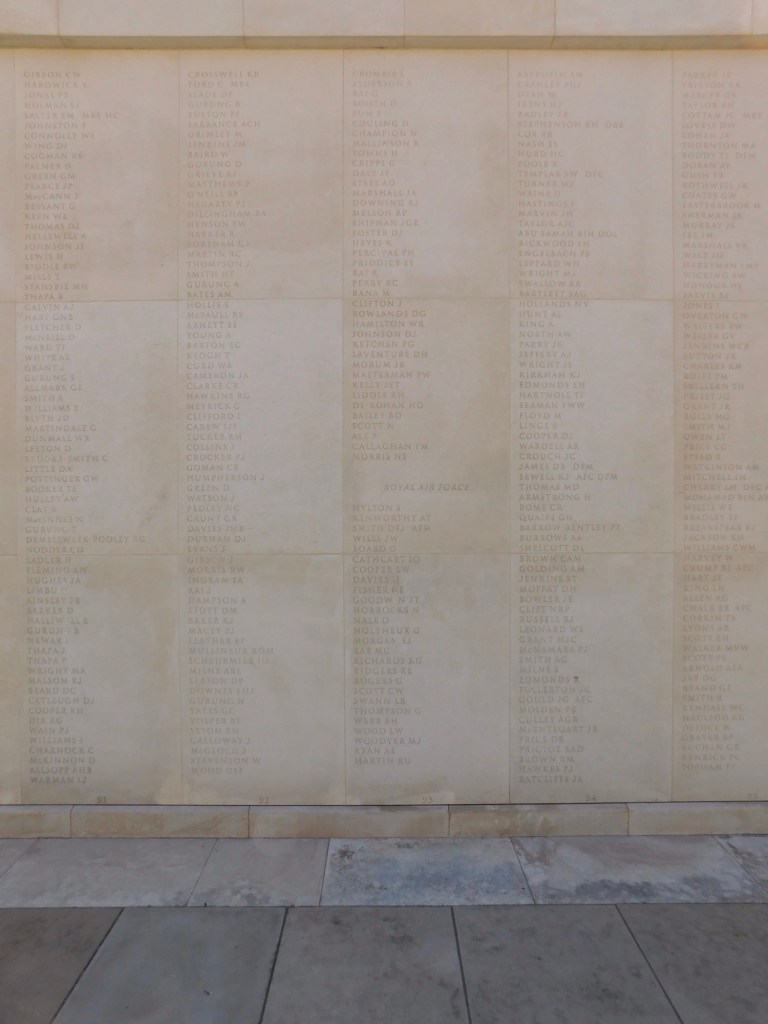

I had provided my uncle’s Armed Forces Memorial roll of honour entry, which is taken from a government database, and gives his full details including service number, regiment, dates of birth and death, and burial place. I believed this to be equivalent to the CWGC roll of honour database, for those who died on, or after, 1 January 1948. Linked to this, he is commemorated on The Armed Forces Memorial at The National Memorial Arboretum. Even this, though, was seemingly insufficient proof of death to open his file.

I found it illogical that whereas a published obituary, or CWGC database entry, were deemed acceptable, the evidence of his death from the government’s own website had not been accepted as proof.

In requesting an internal review of the decision I asked if the matter of acceptable proof of death in these specific circumstances could be looked at. I also asked for an explanation as to why the Government’s own Armed Forces Roll of Honour was seemingly not an acceptable proof of death, when published obituaries (which have discriminatory bias towards Officers) and CWGC website deaths were.

On 20 September 2024, over 11 months after my internal review request, I received a decision.

The original ruling has been overturned. I have also received an apology. My uncle’s entry on the National Roll of Honour is an accepted proof of death, should have been accepted as such when I first submitted it, and the case should have been progressed based on it. I hope the acknowledgment of acceptance of this evidence source will help others who apply under similar circumstances.

But the most important outcome of all for my family is his file – running to 173 pages, and including photos – has now been sent to me in full.

It will take some time to read through and digest. I’m finding it impossible to read in one sitting, mainly because I am frequently being reduced to tears by the pieces I have read, with the family’s anguish still palpable around 70 years later.

I’m reminded of the words of another of my uncle’s back in 2012 when being interviewed about his brother’s death when his name was added to a local War Memorial: “It broke my mum and dad’s heart. You never forget about it.” He was 80 when he spoke these words. The War Memorial unveiling meant so much, because my uncle’s body was never repatriated, and the country in which he is buried is inaccessible – at the time of his death the family were told they had to wait two years, and then they would have to pay the costs of repatriation. The costs quoted were astronomical. All this is documented in the file.

Reading the file I am also continually reminded of mum. She was only 15 when her brother died. Many of the things she told me over the years about the events surrounding her brother’s death are in his service papers. She died last summer, but I know she would have welcomed the final release of his files.