That’s it for another year. The annual Heritage Open Days festival is over. It has been another wonderful celebration of England’s history, culture and heritage, providing a unique opportunity to explore and experience hundreds of local gems for free. It’s a great way to find out about history on your doorstep.

As ever, there was something for everyone – from walks, talks and building tours, to hands-on sessions including having a go at bell-ringing, railway signal-box changing, and stone-carving, including ones specially designed for children. Some events had to be pre-booked and, as I found out, they are really popular. The Oakwell Hall and Shibden Hall tours had gone way before the events days. But many more, for the less organised (like me!!) were drop-in. There are even some online options too.

2024’s event marked the 30th anniversary of this community-led celebration, and ran from 6-15 September. I went to six events all very local to me, including one in my own home!

The first was an event organised by Spen Valley’s Civic Society, who have restored three heritage waymakers, a perfect fit for this year’s theme of routes, networks and connections. These were unveiled by local MP Kim Leadbeater. I went to the first unveiling, an historic fingerpost sign on an ancient route crossing through Hightown, Liversedge. A Roman road, then a packhorse way, in 1740 the route became a turnpike (toll) road from Wakefield to Halifax. The blustery weather perfectly illustrated why the finger pointing towards Huddersfield is along a road now named Windybank Lane – with that ‘veil’ being whisked off by the wind rather than by the MP.

Rather than drive for the unveiling of the two milestones, I walked back home via Spen Valley’s oldest Scheduled Monument, the stone base of Walton Cross, probably a Saxon waymarker and preaching cross.

My next visit was to Whitechapel, Cleckheaton, whose history reaches back to the 12th century. It remains a thriving parish community today, cherishing its past and caring for its amazing building and contents. I was blown away by the history here.

The present day church building was erected in 1820, but there has been a place of worship here since Norman times. And that long history is very much in evidence. Every corner held a fascinating story, and I’ve described only a small selection of the points of interest here.

Tended to by volunteers, the graveyard is exactly how you imagine one to be: Cool, dappled green shade beneath tangled trees, a wildlife haven crammed full of higgledy-piggledy grey, weathered headstones which need concentration to tentatively pick your way around. And deep within, it contains a Brontë connection. the gravestone of 93-year-old Rose Ann Heslip, niece of Patrick Brontë. The cousin of Charlotte, Emily and Anne, she died in 1915.

In the doorway, its etched design almost worn away with time, is an early 12th century grave slab of a Knight Hospitaller.

Inside, I climbed the stairs up to the bell-ringing chamber. Here was another surprise, because I was not confronted by the expected several dangling ropes/bell pulls. Instead there was a weird contraption of numbered pulleys fixed in a frame. This is the ‘Ellacombe’ system, and allows one person to play all eight bells from a single panel. It was devised in 1821 by Reverend Henry Thomas Ellacombe of Bitton, Gloucestershire, to remove the need to use his unruly local ringers of whom he later said ‘a more drunken set of fellows could not be found’. Needless to say, I had a go – and I found it far more difficult than I anticipated. I did get a sound or two, but that was it.

The parish’s war dead are commemorated throughout the church. This includes the porch which was built as a memorial to all who had lost their lives, with some having stained glass memorial windows dedicated to them. Below are photographs of the Tetlow window, and the one dedicated to 2nd Lieutenant Tom Jowett. If you look carefully you can see the figures on which their faces are depicted.

Beneath the window dedicated to Lieutenant Luke Mallinson Tetlow is his original grave marker.

The wooden altar, dating from 1924, was carved by the William Morris-influenced Jackson’s of Coley. Harry Percy Jackson used only traditional tools to produce his intricately carved pieces, and admired Morris so much he named his house Morriscot.

I’ve left the most astonishing feature till last. The font. And it is a very special one. Still used for baptisms, it dates from no later than 1120 and is encircled with carved chevrons, foliate scrolls, and human figures. One of these figures is unique. Grotesque and overtly sexual, some would say lewd, it is a figure of a woman with a deeply carved cleft between her legs and both her hands gesturing towards it.

This style of exhibitionist figure is known as a Sheela Na Gig. They are typically found carved on Norman churches, often over doors or windows. They are seen across Britain, Ireland, France and Spain and Ireland.

Their origin and meaning is debated. They may have Celtic Pagan roots; or they might have fertility connections; they may serve as a warning against lust; they could even be protective symbols to ward off death and evil. But whatever their origin and meaning, Whitechapel’s Sheela Na Gig is unique in Britain, being the only one on a font. Perhaps its symbolism in this instance was to ward off the dangers surrounding childbirth.

Cromwell’s Puritans, who destroyed all traditional forms of worship like stained glass window, fonts, wooden screens, altar furnishing, even decoration on church walls, would presumably have been apoplectic with this font. It is thought that they dumped it in the churchyard. Thankfully, it was later rescued, brought inside and eventually restored as Whitechapel’s baptismal font.

If you want to know more about them, there is a project solely dedicated to Sheela Na Gigs, which includes the Whitechapel font. It can be found here.

My next stop was the Parish Church of All Saints, Batley. The Domesday book of 1086 records the existence of a church and priest here. The present building was erected in around 1485, incorporating parts of the 13th century church. It was restored in 1872-3 by Walter Hanstock of the Batley architect firm, responsible for many of the Victorian public buildings in the town.

Taking a look inside, the font at Batley All Saints did not survive the rule of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan zealots of the Commonwealth period, who cast it out. The replacement 8-sided, ribbed font bears the date 1662, indicating this was installed following the restoration of the monarchy.

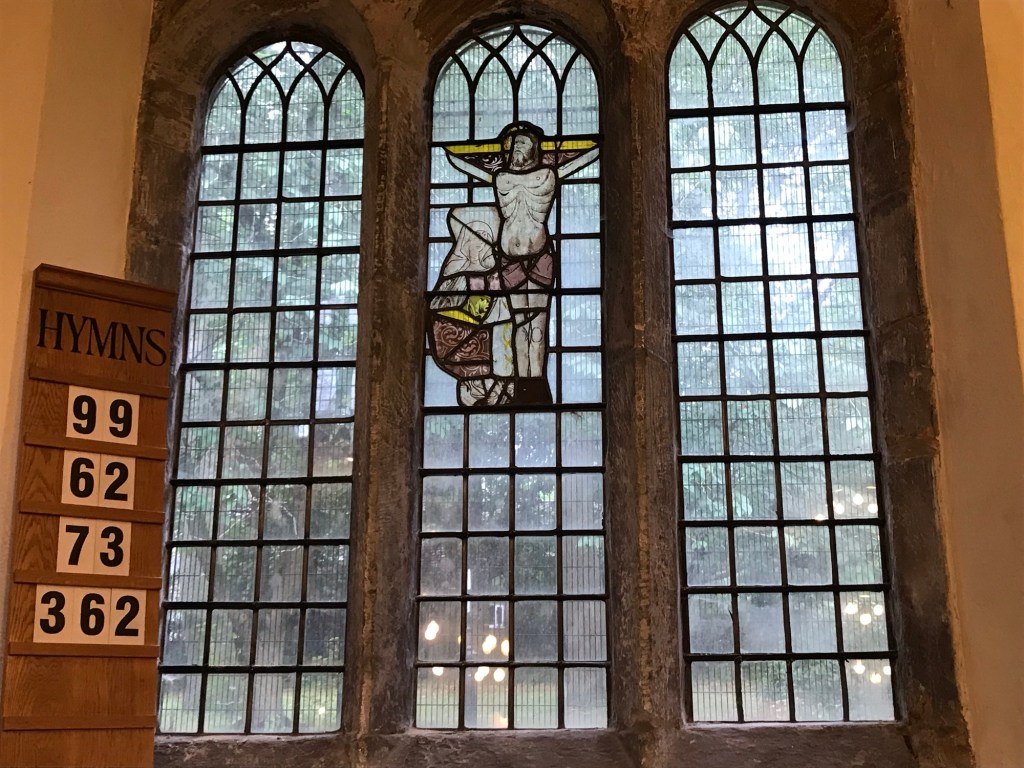

The church also has an impressive example of recycling. When a 14th century stained glass window was broken, rather than throwing away the shattered pieces, some were arranged to form a crucifixion scene in a new window, which is shown in the photograph below.

The east bay Mirfield Chapel, dedicated to St Anne, dates to circa 1485. This side chapel is separated from the church by a completely preserved 15th century wooden parclose screen. The side chapel contains a monumental tomb, which is topped with two alabaster effigies, circa 1496, of a knight and his Lady. The knight’s feet are resting on a recumbent lion. These figures depict Sir William and Lady Anne Mirfield.

The stone tomb chest itself has around it a series of severely age-worn low relief carvings of ladies holding shields. The shields related to four generations of the Mirfield family at Howley Hall. Fortunately, an early 19th century engraving has survived which shows what this carving looked like before the erosion damage.

‘TOMB OF MIRFIELD AT BATLEY. T. Taylor, delt. W. Woolnoth, sculpt. Published by Robinson Son & Holdsworth Leeds, & J. Hurst Wakefield March 1. 1816.’ University of Leicester Centre for Regional and Local History. http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

The Copley chapel, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, was founded by the Lord of Batley Manor, Adam de Copley, in 1334. Generations of the Copley family are buried beneath the floor. This parclose screen, adorned with Copley family shields, mermen and dragons, dates from the second half of the 16th century, a replacement for an earlier one. There is also some 1852 restoration to it, using cast iron to replace missing and damaged carvings.

Given my family history fascination, I was drawn to two wooden plaques. These record charitable donations and benefactions left in wills for Batley’s poor, church and school. I love that James Shepley’s yearly-for-ever £10 donation to the vicar of Batley came with strings attached. It would only be paid if he preached a sermon every Sunday morning and afternoon throughout the year!

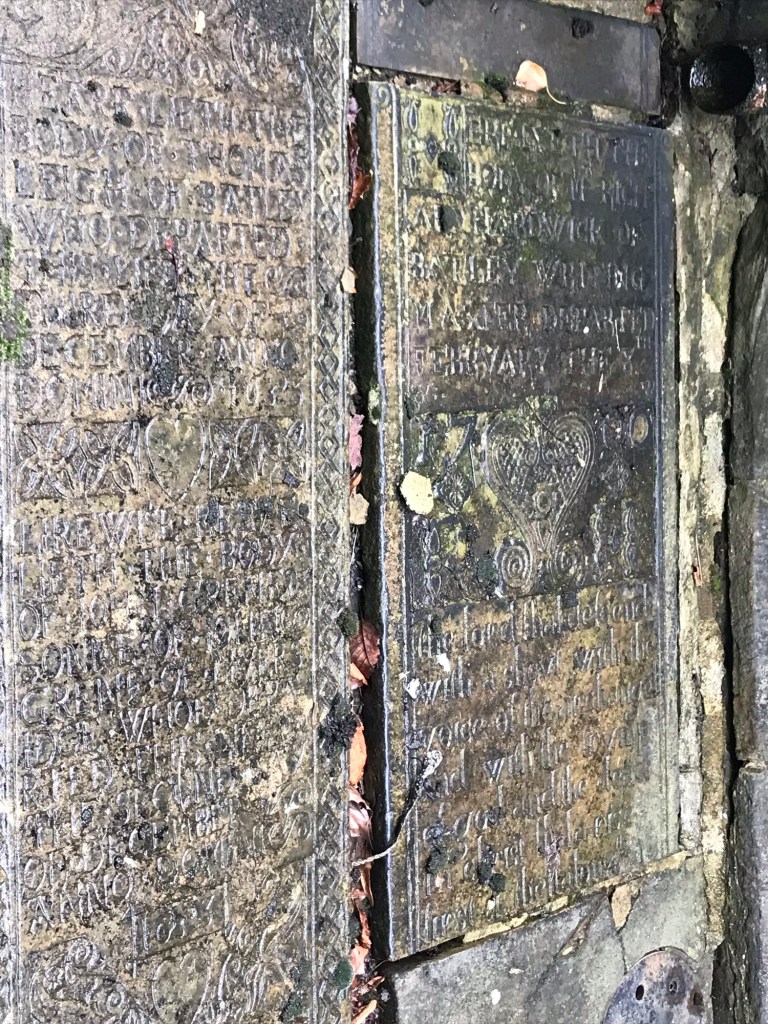

Back outside, I had a final look at some of the grave slabs inlaid into the path, some with intricate etched hearts dating from the mid-17th century. These heart carvings are quite rare, apparently only being found within the Calder Valley area.

One particularly intriguing feature lies to the east of the porch. Believed to date from the 13th century, and described by Michael Sheard in his 1894 History of Batley as ‘a mutilated stone effigy’, its history is unclear, the figure bearing no date, inscription or other identifying feature. Morley historian Norrisson Scatcherd recounted the tale that it was the grave of a particularly severe schoolmaster, slain with his own sword by his pupils. Sheard disputes this, but his alternative theory is vague. He says it is likely that the figure represents someone from one of the notable Batley families, a Copley, Mirfield, Eland or Dighton. He suggests the effigy was originally inside the church, but removed when the organ was installed in 1830, and placed on a monumental tomb. It is Grade II listed.

On 14 September, I went to one of the Leeds Civic Trust events. Leeds Libraries, Morley Community Archives, Morley and District Family History Society combined to put on event in Morley library. It included old maps, displays about people who played a role in the history of Morley, and information about the town’s old mills. Lots of lovely volunteers were on hand to answer local and family history questions. There was also a virtual tour of Morley Town Hall.

This imposing Grade I Listed building was opened on 16 October 1895 by Morley-born Rt. Hon. H. H. Asquith MP, who went on to be Prime Minister from 1908-1916.

It was fascinating being guided virtually around the exterior and interior of the building, including the old police cells and former magistrates courtroom.

My final in-person Heritage Open Day visit of 2024 was the parish church of St Peter’s, Hartshead. It is yet another local church with a rich history, entwined with folklore. It also has a family history connection for me, being the church in which my 3x great grandparents married in 1842.

Thought to be of Saxon origin, there is a Norman tower, south doorway and chancel arch. The rest of the church is an 1881 restoration in the Neo-Norman style. But despite these early origins, Hartshead did not become an Ecclesiastical Parish until 1742, created from Dewsbury [All Saints] Ancient Parish.

Hartshead church is another which bears the scars of Puritan destruction during Cromwell’s Commonwealth period. The original font has gone. The replacement, only the bowl being present which is no longer in use, like Batley bears the date 1662. The font in use is more modern, but has a base formed from an old Norman pillar.

In the above photo, in addition to the fonts you can see the bell tower, in which one bell hangs. Two more, dated 1627 and 1701, are no longer in use. My husband was invited to test the weight and, trust me, they are immovable. He did have a go at ringing the electronic bell with more success. There is an associated rhyme about the Hartshead church bells:

Hartchit-cum-Clifton,

Two cracked bells, an’ a chipped ‘un

Hartchit-cum-Clifton

Two cracked bells, an’ a snipt ‘un

Now for that Brontë connection, so much in evidence across the area. Patrick Brontë was appointed vicar at Hartshead in 1810, moving to this parish from Dewsbury where he served as curate. Although the official date of his Hartshead appointment was 1810, it is not until the following year that he appears to have formally taken up the role. He remained at the parish until 1815, when he moved to Thornton.

It was whilst at Hartshead that he courted and married Maria Branwell (on 29 December 1812, though the marriage took place in Guisley); and where their first two daughters – Maria and Elizabeth – were born. In fact, eldest daughter Maria was baptised at Hartshead.

And writing of baptisms, a Hartshead parish register – normally held at West Yorkshire Archives – was on display, there to be handled. The condition of it was superb, no doubt helped by its thick, high quality pages, clearly made to survive. If you look at the photograph, you will see the signature of the officiating minister of the 1813 baptisms – P. Brontë. It really was a case of touching Brontë history! Leaving aside my family history obsession, If you read my previous post about another amazing piece of Brontë history at Haworth I came across only two days before, you’ll know how big a deal this register was to me.

The parish register was the tip of the information iceberg. From displays of school records, to memorabilia about parish events and shows, there was so much loaned-for-the-day material to look at.

Back to Patrick Brontë though. It was before his marriage, whilst lodging at Lousy Thorn Farm, that under cover of darkness on the night of 11 April 1812 a large force of men (numbering anything between 150-300), armed with hammers and axes, passed by Hartshead church and Patrick’s lodgings.

The desperate gang worked as croppers. It was a highly skilled job which demanded strength too. As a result, it commanded a good wage. The work was slow and laborious, with the men closely cropping rolls of fine cloth with heavy shears, weighing in excess of 40lbs. Cropping away the nap on the cloth left a fine, smooth surface. And the finer and smoother the surface, the more valuable the cloth was.

But their livelihoods were now being destroyed by the advent of water-powered machines which could be operated manually by an unskilled worker, with one unskilled person now able to do the work of four skilled croppers. It meant large numbers of croppers were being made redundant, and their families facing starvation as a result. The croppers therefore became part of the Luddite movement, whose aim was to destroy the machinery threatening their jobs.

Their destination that night was William Cartwright’s mill at Rawfolds. Cartwright had installed new cropping machinery, and their objective was to destroy it, in an attack planned for the early hours of 12 April 1812.

But Cartwright was ready for them, with the mill heavily fortified and defended by a body of employees, and five militia soldiers especially drafted in.

In the ensuing 20-minute battle, shots were fired (an estimated 140 by the defenders). The attack failed and the Luddites were driven away. Two Luddites were killed, their bodies left in the mill vicinity. Many more were injured. Daylight revealed pools of blood outside, along with flesh and even a finger. 17 Luddites were later hanged at York, some for their part in the attack.

So, how is this Luddite attack at Rawfolds connected with Hartshead church? It is thought some of the injured men did in fact die, and were buried in secret that night in the south east corner of the churchyard at Hartshead. Harold Norman Pobjoy, a former Hartshead incumbent, says it is believed Patrick Brontë knew about the burials, seeing the freshly disturbed earth and footprints, but resolved, compassionately, to say nothing.

Beyond the supposed Luddite burials, the area outside the church has several other points of interest. The day’s rain and grey skies meant the usually glorious views were not amongst them! However, there were plenty others to investigate.

In the churchyard stands the gnarled remains of an ancient yew tree, with mesmerisingly intricate whorls.

Local folklore links this tree to Robin Hood, with his final arrow being cut from it. He was reputed to be the nephew of the Prioress at nearby Kirklees Priory, where he sought refuge in his final days. Here, she bled him, a cure-all for multiple ailments in medieval times. But for whatever reason, it went wrong, she cut one of his veins, and he slowly bled to death. Some versions say it was a deliberate act as she resented Robin’s criticism of the church hierarchy, and the fact he was not averse to relieving Abbots of their wealth to give to the poor. Another attributed motive is that she was the secret mistress of one of Robin Hood’s sworn enemies, Roger of Doncaster.

Robin Hood’s supposed burial place, which now lies in Kirklees Park estate, is where his final arrow shot landed – the arrow cut from the Hartshead yew tree.

The Hartshead stocks survive, as does a mounting block for those arriving at the church on horseback. Neither are in much demand today. Both are Grade II Listed, and date from the 18th or 19th centuries according to their Listing entries

Lastly, there is a small building forming part of the boundary wall. This too is Grade II Listed. I’ve often wondered what purpose it served, and today I found out. Dating from around 1828, it was formerly a school room, and the old coat pegs remain affixed against one of the inside walls – though with the bricked-up door and windows, plus piles of junk, it was difficult to see in any detail.

Before being a school though, the building was originally a bier house. It would have contained a bier (moveable stand) on which a corpse – often in a coffin – would be placed prior to burial. We were also told corpses travelling distances for burial, for example Liverpool to Hull, would use this building as an overnight stop-off point on the journey. It’s to be hoped, for the sake of the school children, there was no overlap between the building’s two uses!

Finally, for those not able to get out and about, online events were available. I rounded off this year’s Heritage Open Day festival with a YouTube talk by Professor Joyce Hill called Time Travel through Place Names, exploring the place names in Leeds, their origins, and how they reveal the city’s history.

It was fascinating to learn how the place names in and around Leeds are rooted in past history, with a combination of Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Scandinavian influences – and some melding and overlapping of language over time. For instance, Burley in Wharfedale’s name draws on Celtic, Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian periods of our history.

Professor Hill also demonstrated how these names can give an indication of the type of landscape, activities undertaken, or people who lived there – even though these may no longer be in evidence. For example, Seacroft means a croft by a lake. Morley has its origins in the Old English leah (clearing/open place in a wood), and mor meaning marsh. Farsley means a woodland clearing used for heifers.

Roads, too, can give clues to the past. Briggate was one example cited, with gate being from the Scandinavian word gata, meaning path or way, and bryggr being bridge. So Briggate’s Scandinavian translation to English is Bridge Street.

There was also the cautionary note to go back to the earliest recorded forms of the name and not make assumptions based on more recent meanings. For example, Boar Lane has nothing to do with the animal. It was originally Borough Lane, the lane linking the Borough to the King’s Mills, and the word evolved to Boar.

Whitkirk is similarly misleading. Although it does mean white church, the white is a reference not to the colour, but to the Knights Templar who were associated with the area. They were known as the White Knights. Furthermore, even though the Vikings had long gone when Whitkirk was named, their influence on the language remained, with the kirk in this instance being from the Scandinavian word for church.

A huge debt of gratitude is owed to the many volunteers up and down the country who have invested their time over many months to put on these events and open up buildings. Many work tirelessly year after year keeping our history alive – often in the face of swingeing council cutbacks to all things history and heritage locally.

Caring for history and heritage is a year-round process, not something that happens for a few days a year. And, as I learned, many of the church sites are cared for not only by the congregations but by others who don’t attend church, but are simply interested in their local history and heritage.

Hopefully, the events this year will inspire others to get involved and champion local history, whilst at the same time sending a signal to councils that our local history and heritage is valued, plays a pivotal part in the way people regard an area, and enriches the lives of those who live there.