Name: Michael Hopkins

Rank: Private

Unit/Regiment: 9th (Service), The King’s Own (Yorkshire Light Infantry)

Service Number: 3/866

Date of Death: 1 July 1916

Cemetery: Gordon Dump Cemetery, Ovillers-La-Boiselle, Somme, France

Michael Hopkins was born on 27 September 1894.1 Though later records indicate a Charlestown birthplace, his birth certificate records it as Bella[g]hy, where the family home was at the time.2 Bellaghy directly adjoins Charlestown, with the former in County Sligo and the latter in County Mayo.

He was the son of labourer Pat Hopkins and wife Bridget (née Boyle), who married in December 1886 in Kilbeagh parish. Their other 12 children included Mary Ellen (born 1887), John (born 1889), Bridget (born 1891), Patrick (born 1892), Thomas (born 1896), Martin (born 1898), Catherine (born 1901), Bernard (born 1903), and Margaret (born 1906).

It was shortly after Margaret’s birth that most of the family first crossed the Irish Sea to reside in Batley.3 They lived at Cooper Street, with Pat initially working at Messrs. Crossland, contractors based on Healey Lane. However, at Christmas 1907 he made the fateful decision to work as a hopper trimmer at Soothill Wood Coke Ovens, a job his wife said he enjoyed.4 In turn his employers said Pat “was a man of excellent character and most reliable.”5

Burning at a much higher temperature than pure coal, coke was a key component in blast furnaces of Britain, used to produce the cast iron so vital to an industrial power.

On Wednesday 8 July 1908 Pat left for work as usual at 5.30 am. His job entailed working in the 30-foot wide and 22-foot deep containers, known as hoppers, where slack, the fragments of coal and coal dust used for coke production, was stored.

Around 50 times each hour a crane operator using a grab (weighing 6-8 cwt) lifted slack (weighing 4½ cwt) from the centre of the hopper.6 The hopper trimmer ensured the slack was shovelled into position for the grab. It was a dangerous environment to work in, and the hopper trimmer had strict instructions to avoid the centre of the hopper.

When the hopper was emptied of slack, Pat’s next job was to use a hosepipe to clean out the hopper drains. Meanwhile the crane operator moved on to empty the slack from a neighbouring hopper.

However, in wet weather the grab brake was prone to slipping, even when quick lime was applied. At just after 3 o’clock the brakes gave way and the grab fell into the already emptied hopper – the one which Pat was still cleaning. The crane driver pulled the grab out, more quick lime was applied, and he carried on working, oblivious to the fact that Pat was in that hopper. It was going on for half an hour before the accident was discovered. Pat was found lying dead, his neck fractured and jaw broken, the grab clearly having hit him. Death would have been instantaneous.

His bitterly weeping wife was amongst those giving evidence at his inquest, held at Batley Town Hall the following day. The jury’s verdict was Pat was accidentally killed through being struck by the grab, owing to the brake slipping.7

The Hopkins family dispersed following the accident. Whilst the younger children stayed with Bridget, who for a short while returned to Ireland, the older ones lived in other households across Batley.

In the 1911 census 16-year-old Michael was lodging at Fleming Street in the home of Patrick and Margaret Hopkins. Their 16-year-old son Patrick, also present, would become another St Mary’s casualty of the war.

In 1911 Michael was employed as a colliery trammer,8 conveying empty coal tubs to the face and takes the full ones back to the pit shaft ready to be taken to the surface. It is probable that at this point he worked at Messrs. Critchley’s Batley Colliery, and by the time war broke out he had risen to the responsible position of deputy there.9 This meant he was in charge of a section of seam, and his duties would include ensuring ventilation met requirements, taking temperature and barometer readings, and making general safety reports.10

From his service number prefix, it is very likely Michael was in the Special Reserve. This cohort undertook an intensive period of initial training, topped up by annual camps to refresh skills, with the aim of creating a pool of trained men to call upon to reinforce the Regular Army in the event of war. When war broke out, according to newspaper reports, Michael was undertaking his fourth period of training. He was retained for immediate service and went to the Front in early October 1914.

He served initially with the 2nd Battalion of King’s Own (Yorkshire Light Infantry) (KOYLI). The Battalion suffered heavy losses in August 1914, in the British Expeditionary Force’s first major action at Mons, and in the subsequent Battle of Le Cateau. Michael was amongst those men sent out to bring them back up to strength.

His brothers John and Patrick were also with the Colours. John was initially with the local Territorials, the 1st/4th KOYLI, before his transfer to a motor transport role. Patrick served as a Sapper in the Royal Engineers.11 For a while Michael and Patrick were together in France, but in a letter to his mother in November 1914 Michael said that they had now been separated for some weeks.12

A third brother, Martin, wanted to enlist but was rejected as being under age. Despite the dangers his brothers faced serving King and country, it was Martin, who worked as a piecener in Batley, who died first. This was on 18 March 1916. He was buried alongside his father in Batley cemetery.

Michael did have a couple of narrow escapes, being twice wounded, on one occasion by bayonet and on another being hit by a bullet. One was a hip injury, the other an arm. He also suffered frost bite.13 Some time after the summer of 1915 – possibly following recuperation from one of these injuries – he transferred to the 9th KOYLI.

In the summer of 1916, in his final letter home, Michael was in confident mood. It was clear to the men that a major operation was in the offing. St Mary’s parishioner Herbert Booth, in the same Battalion as Michael, penned a final letter to his brother indicating this. Michael’s letter also hinted at a forthcoming battle. Enclosing a photo of himself and two comrades he wrote:

These are the boys that will give the Germans what Paddy gave the drum when we meet them, and I hope that won’t be very long.14

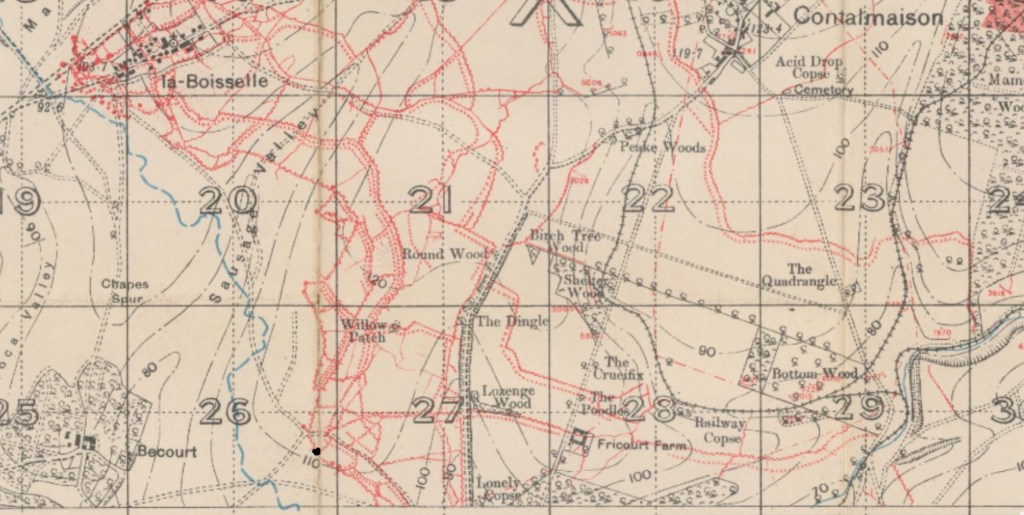

That meeting was 1 July 1916, on the opening day of the Battle of the Somme. That day, the 9th KOYLI were involved in the 64th Brigade attack north of the village of Fricourt, with a position known as Crucifix Trench being an initial objective. Its name derived from the crucifix which stood just above it between three tall trees.

The original assault, scheduled for 29 June, was delayed for 48 hours due to bad weather. As the bombardment of the German lines continued, on the evening of the 30 June the men, each carrying a staggering 66lbs of equipment, proceeded to their assembly positions, a move completed by 11pm.15 It was now a case of waiting for Zero Hour, set for 7.30 the following morning. The War Diary notes one piece of relief to the tension – the arrival of tea and rum for the men in the early hours.

At 7.25am, during eight minutes of intense bombardment, the leading platoons of A and C Companies emerged from their assembly point and crawled forward under the heavy barrage. As the barrage lifted at 7.30am the attack commenced and the men moved forward in waves across no-mans land.

The Operation Orders instructed the men to move in quick time towards their objective. It also notes:

The use of the word RETIRE is absolutely forbidden in this Division. All ranks are distinctly to understand that if such an order is given, it is either a device of the enemy, or is given by some person who has lost his head. In any case, this order is never to be obeyed.16

Withdrawal was only allowed via a written and signed order.

In another part of the discipline instructions, the natural tendency of men to pick up souvenirs was discouraged in the strongest terms:

The attack is not going to be a curio hunt. Any tendency to waste time in looking for, or picking up, curios, is to be checked AT ONCE. Positions are to be immediately consolidated, and troops made ready to meet enemy counter-attack. Any Officer, N.C.O., or man found in possession of any curio or souvenir will be tried by Court Martial.

Souvenirs will be collected under Divisional arrangements, and distributed to the Units taking part in the attack.17

It is a revealing order, with the perception that men might have the time and inclination to hunt for souvenirs during the attack and when reaching their objectives, indicating the belief that opposition – following days of pounding from British artillery – would be minimal enough to allow it. The possibility of any curio hunting by the 9th KOYLI was quickly quashed by subsequent events.

The unit war diary goes on to record the initial assault as follows:

When the leading platoons had crawled forward about 25 yards into NO MAN’S LAND, they were greeted by a hail of Machine Gun and Rifle Fire; the enemy, in spite of our barrage, brought his Machine Guns out of his dug outs and placing them on the top of his parapet, opened rapid fire. A and C Companies suffered chiefly under this, while B and D Companies endured chiefly a heavy artillery barrage. When the leading troops were close enough, the enemy also employed cylindrical stick bombs against them.

The battalion suffered heavily in NO MAN’S LAND…18

The 9th KOYLIs advanced crawling and dashing from shell hole to shell hole until they seized the German front-line trench north of Fricourt, then the Sunken Road about 600 or 800 yards behind the front line, and then they finally occupied Crucifix Trench, another 200 or 300 yards further on. But the War diary was correct. They did suffer catastrophic losses. The Unit War Diary for the day records that 22 of the 24 Officers of the Battalion had either been killed or wounded as a result of the action. In addition the diary notes there were 475 casualties in the other ranks, about 145 of whom were killed.19

From his original burial location, it seems Michael did not get beyond the German Front Line.20 The map below indicates, with a black dot, the location where his body was recovered from after the war. The blue line marks the British Front Line, the red ones are the German trenches including their Front Line, and the area between the respective Front Lines is no-man’s land. The Crucifix objective is annotated.

His mother received official intimation of her son’s death on Saturday 22 July 1916. Bridget was awarded a modest pension, initially 10 shillings a week, but increased by a further shilling from 4 April 1917.21 She died in April 1940.

Michael is now buried in Gordon Dump Cemetery, Ovillers-La-Boiselle, his body being laid to rest there after the war, recovered from his original resting place.

Michael was awarded the 1914 Star with clasp (the clasp indicates he served under fire), Victory Medal and British War Medal. In addition to St Mary’s, he is remembered on the Batley War Memorial. He is also honoured on the Mayo Great War Memorial in Mayo Peace Park, Castlebar.

His brothers Patrick and John survived the war.

Postscript:

I may not be able to thank you personally because of your contact detail confidentiality, but I do want to say how much I appreciate the donations already received to keep this website going. They really and truly do help. Thank you.

The website has always been free to use, and I want to continue this policy in the future. However, it does cost me money to operate – from undertaking the research to website hosting costs. In the current difficult economic climate I do have to regularly consider if I can afford to continue running it as a free resource.

If you have enjoyed reading the various pieces, and would like to make a donation towards keeping the website up and running in its current open access format, it would be very much appreciated.

Please click 👉🏻here👈🏻 to be taken to the PayPal donation link. By making a donation you will be helping to keep the website online and freely available for all.

Thank you.

Footnotes:

1. Irish Civil Registration records. His age can be inaccurate in records, for example at the time of his death some newspapers said he was nearly 21. But his birth registration is the definitive evidence of birthdate.

2. Birthplace taken from birth registration details.

3. Married daughter Mary Ellen remained in Ireland with husband Martin Skeffington, although she did eventually make her home in Lancashire after separating from her husband.

4. Batley News and Batley Reporter and Guardian, 10 July 1908.

5. Batley News, 10 July 1908.

6. 1 cwt is 112lbs.

7. Batley News and Batley Reporter and Guardian, 10 July 1908.

8. Also known as a hurrier.

9. Michael seemed young to be a deputy, but that’s what the Batley News in their 5 August 1916 report described him as.

10. A Dictionary of Occupational Terms: Ministry of Labour. Based on the Classification of Occupations Used in the Census of POPULATION, 1921. His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1927.

11. Batley News, 5 August 1916.

12. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 27 November 1914.

13. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 28 July 1916 and Batley News, 5 August 1916.

14. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 28 July 1916.

15. See Herbert Booth for more details about the equipment carried.

16. Operation Orders No36, 9th KOYLI Unit War Diary, TNA, Ref: WO95/2162/1.

17. Ibid.

18. 9th KOYLI Unit War Diary, TNA, Ref: WO95/2162/1.

19. Ibid.

20. Concentration of Graves (Exhumation and Reburials), No. 21 Labour Coy. Burial Return, 5 August 1919, Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

21. WWI Pension Record Cards and Ledgers, Western Front Association, Ref 685/04D, 035/0206/Hoo-Hor, and 102/0462/HOP-HOR.

Other Sources (not directly referenced):

• 1901 and 1911 Censuses, Ireland.

• 1911 and 1921 England and Wales Censuses.

• 1939 Register.

• Batley Cemetery Burial Registers.

• Bond, Reginald C. History of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry in the Great War, 1914-1918. London: P. Lund, Humphries, 1929.

• Civil registration of births, marriages and deaths in Ireland

• Clayton, Derek. From Pontefract to Picardy: the 9th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry in the First World War. Tempus, 2004, including quoting from papers of G. F. Ellenberger, IWM. Fragment from When the Barrage Lifts, B. Liddell Hart, 1920.

• Commonwealth War Graves Commission website.

• GRO Birth, Marriage and Death Indexes – England & Wales.

• Medal Index Card.

• Medal Award Rolls.

• National Library of Scotland maps.

• Newspapers, various.

• Parish Registers, Batley St Mary’s and various Irish parish register transcripts.

• Soldiers Died in the Great War.

• Soldiers’ Effects Registers.

• Spiers, EM, Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme. Northern History, 2016, https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/99480/.

• The Long, Long Trail website.