Name: James Garner

Rank: Private

Unit/Regiment: 10th (Service) Battalion, The King’s Own (Yorkshire Light Infantry)

Service Number: 10542

Date of Death: 1 July 1916

Memorial: Thiepval Memorial, Somme, France

James Garner’s early teenage years may be best categorised as difficult. Described as a “youthful brigand”1 and “a leader of several young thieves”2 after a spree of offences in town which mystified his family, he did successfully turn things round after a spell in a Reformatory. But he was to become yet another St Mary’s parishioner whose life was cut tragically short on the Somme.

James’ surname technically was Boles, not Garner.3 He does appear under both surnames in records. According to his baptismal register entry he was born on 13 October 1889, the son of Catharine (Kate) Boles.4 Locally-born in around 1868, woollen rag sorter Kate and her young son were lodging with the Owens family in Ambler Street in the 1891 census.

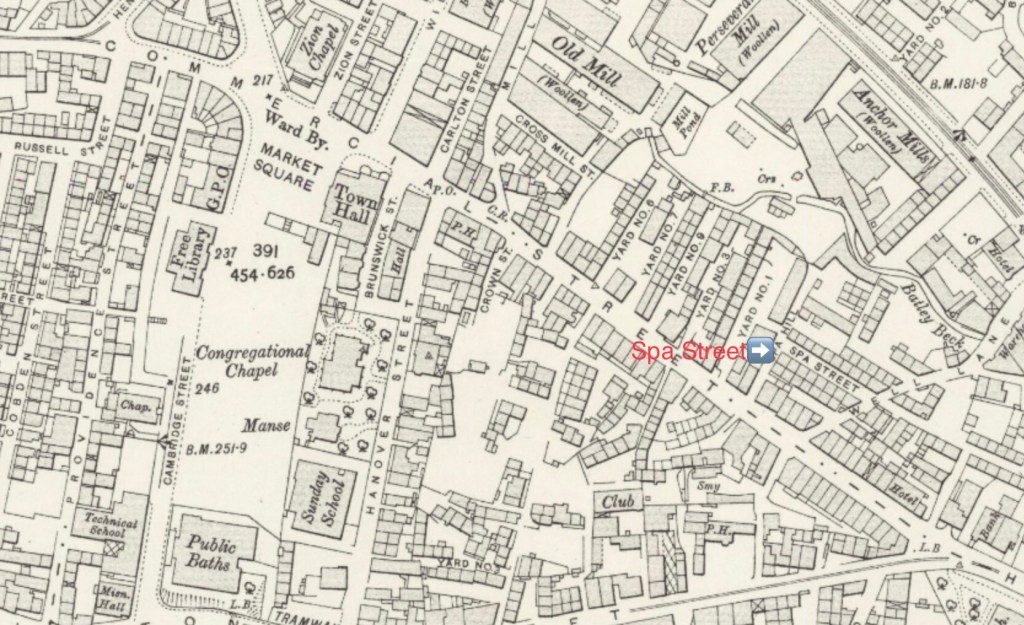

Kate’s marriage to John Garner, a coal miner from Batley, was registered in the Dewsbury registration district in the first quarter of 1892. She and John settled at Spa Street, off Well Lane, in Batley with John bringing up James as his own son. James almost always adopts John’s surname in records, only occasionally using Boles/Bowles. His military service was under the Garner surname.

Following their marriage, John and Kate’s children included Mary Elizabeth (born in 1892), Michael (born 1894), Margaret (born 1895), Catherine Ellen (born 1898), Agnes (born 1900), Ann (born 1902), Ellen (born 1903) and John (born 1906).

Five of these eight children died in infancy or early childhood – Michael in 1896, Margaret in 1901, Ann and Ellen both in 1903 and John in 1906. Two – Margaret and Ellen – died in particularly shocking circumstances, their deaths the subject of inquests.

Margaret suffered a horrific death. At just after midday on Saturday 30 November 1901 Kate went to a neighbour’s house for only a few minutes, leaving six-year-old Margaret outside. Shortly afterwards Joseph Liversedge, a teenage cloth finisher and St Mary’s parishioner who lived near by, heard a child’s screams. He ran to help and found Margaret standing outside the door in flames. He took off his coat to smother the flames, removed her smouldering clothes and got a cab to take her to Batley cottage hospital. Before getting in the cab, Commercial Street confectioner Levi Stead provided Kate with some limewater to cool down Margaret’s burns.

By Kate’s admission Margaret was fond of lighting things at the fire, and in the cab on the way to hospital Margaret told her mum she’d lit a candle and covered it with her cotton pinafore. The ‘pinny’ caught fire.

Margaret suffered burns to the lower part of her face, both hands and her left arm – the latter being described by Miss Cann, the hospital matron, as very severe. Doctor Potter, who saw her shortly after arrival, gave her little hope of recovery and she died at 8 o’clock on Monday morning.5

The inquest jury returned a verdict of “Accidental death”, with the Coroner praising the actions of Joseph Liversedge in dealing with the incident and his efforts to save the child.

Two years later, on 3 December 1903, the Garner’s 10-day-old daughter Ellen died at 4.10 a.m. This proved a controversial death, with the initial inquest adjourned in order to have a post mortem because of the contradictory evidence provided by John and Kate.

It seems Ellen slept in the same bed as her parents, with another daughter (possibly Agnes, though the reports do not name her) sleeping at the foot of the same bed.

Kate said that during Wednesday night Ellen had a screaming fit and she gave her some cinder water to try calm her. This was an old remedy for coughs, or to treat babies suffering from wind. A red-hot cinder was dropped in a container of water and the mixture sieved through a muslin cloth to separate out the ashes. The sieved liquid was then given to the infant.

Ellen did go back to sleep. But shortly before 4 o’clock in the morning she once more screamed and Kate noticed her turning black. She said the child lived around five minutes after she made the noise; John, who went out in search of a policeman, said ten.

Catherine Liversedge, mother of Joseph (the teenager praised for his attempts to save Margaret two years earlier), was called round to the Garner’s house at around 4.20 a.m. Kate told her she thought Ellen had died as the result of a fit.

Dr. Bennett, who conducted the post-mortem, disagreed. He said the only conclusion was the child had been overlaid whilst in bed with her parents, and suffocated. This was the verdict reached by the jury.

In concluding, deputy coroner Mr C. J. Haworth criticised the parents’ evidence saying that whilst he did not like to say they had committed perjury, he was bound to say their evidence had been very unsatisfactory.

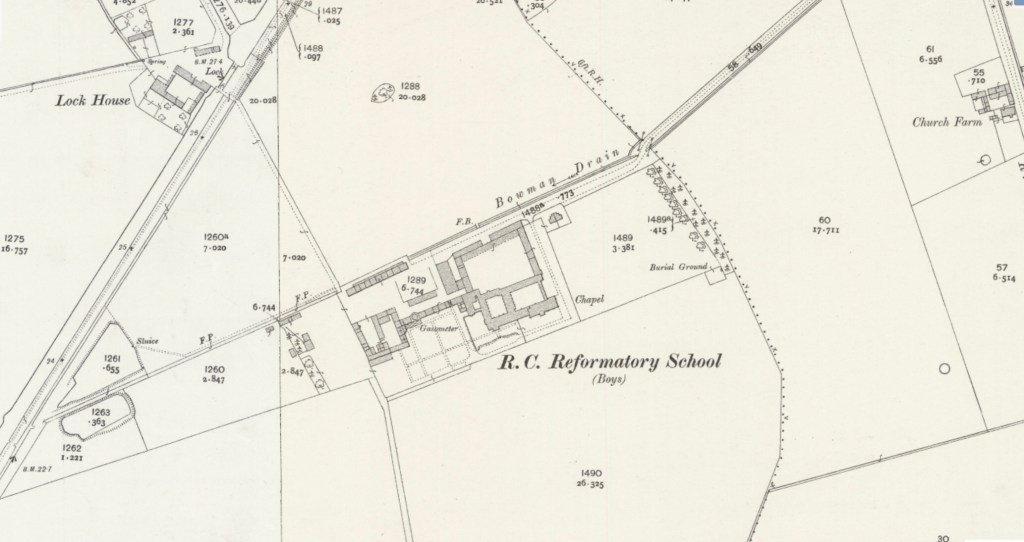

But 14-year-old James was not living at home when Ellen died. He was serving out a sentence at The Yorkshire Catholic Reformatory School for Boys. The Institute of Charity, more usually known as the Rosminians, operated this establishment.

The Reformatory system was established in 1854 for under-16s convicted of crime. With concern about the way children were treated in the criminal system, the Philanthropic Society was at the forefront of this change to the criminal system. Children sent to Reformatory schools spent between two to five years there. However, until 1899, those committed to such establishments still spent 14 days in an adult prison first. This was thankfully no longer the case by the time of James’ sentence.

Although located two miles east of Holme upon Spalding Moor in the East Riding of Yorkshire, Market Weighton was the location commonly associated with the school, because this was the nearest railway station. It was a remote, rural location. The work the boys undertook reflected its countryside locality, with a proportion dividing their time between studies and farm labouring. Other trades included shoemakers, bricklayers, printers, tailors, bookbinders, laundry and horse boys. The education and training provided there was intended to dissuade the boys from a life of crime, and equip them for work once they left.

In July 1906, whilst James was at the reformatory, when the establishment celebrated its Golden Jubilee, it was described as:

…a most interesting institution; an educational establishment where not only is secular and religious instruction imparted, but where firm discipline reigns, and where trades are taught, and its inmates trained to become useful members of society. The buildings are of an extensive character, and comprise a chapel (part of the original structure), large school and class rooms, recreation rooms, dormitories, refectory, and workshops, besides farm buildings, for the school is surrounded by about 400 acres6 which are worked by the boys.7

When James arrived on 17 March 1903 Father Castellano was in charge. He had been its superintendent since 1865. The annual reports of the Home Office chief inspector were critical in the lead up to James’ admission, including a focus on the reformatory’s unfavourable death rate.

Bathing was a perennial thorny topic, with Father Castellano setting the lead boasting he had never had a bath in his life. In 1882 the inspector’s report noted a bath was much wanted. It was not built until 1900. But even after the provision of a bath, water supply remained problematical. For example, in 1902 it was reported that the hand pump which supplied the reformatory was inadequate and the bath could be used only once every three weeks in winter.8

In other criticisms, in 1898 the inspector wrote:

We must face the fact – Market Weighton is not up to the standard of other reformatories.9

In 1899 he was even more critical:

An effort must be made or the future of the institution cannot be guaranteed.10

By 1905 when James was there the report found so much fault and was so critical of almost every part of the establishment that Father Castellano could not remain in post. In September 1906, he was replaced by the Rev. Charles Ottway, who renamed the establishment St William’s School for Training Catholic Boys. Other changes included to the uniform – plain cord knickers and a tweed coat. But despite these cosmetic changes, conditions did not really improve.

So why did James end up in a Catholic Reformatory?

The train of events began at lunchtime of 6 October 1902. At around 12.30 he and another schoolboy, John Armstead, pulled about 20 stones off a wall in Carlinghow Lane. A police constable observed the offence and, as a result, James (appearing under the surname Garner) ended up before Batley magistrates the following Monday, 13 October. It happened to be his birthday, something pointed out by his mother in her plea for leniency. Both James and John promised not to offend in future, and the Mayor let them off with a fine of 2s 6d each, and a caution not to be mischievous again. Except the promise was not kept…by either boy.

On 5 December 1902 James was back in Batley Borough Court once more (this time under the surname Bowles), along with previous accomplice 11-year-old John Armstead, and a new recruit, 13-year-old Charles Craven. They were accused of breaking into two shops.

At some time overnight of the 3/4 December the trio removed a pane of glass and broke into the property of Bradford Road refreshment houser keeper Charles Armitage Henderson, stealing 15 packets of cigarettes, matches, chocolate, nuts, three shillings worth of buns, nine bottles of ginger beer, six glasses, three indiarubber balls, two dozen pies, a clock (which they pawned in a Batley Carr shop), knife, salt box, vinegar bottle, three dozen Christmas stockings, wax carriage candles, toffee, a draught board and draughts, six pounds of tripe, three pounds of ordinary candles and a basket. The total value of their wide-ranging pre-Christmas haul was £3.

The police found the lads in Bradford Road on Thursday morning in a dirty condition, smoking cigarettes. They raised suspicion, so Sergeant Blackburn took them to his house and made them empty their pockets – revealing a variety of goods including cigarettes, tripe and nuts. Initially they claimed to have found them in Caledonia Road, before finally admitting to breaking into Mr Henderson’s shop.

Subsequently the police found out the lads had used a stable behind the shop for the consumption and storage of their ill-gotten gains. Here the police also found three lamps which they had used at night – stolen from Mr Benjamin Rogers’ blacksmith shop in Cross Street, together with a watch.

Bail was refused and they were remanded in custody for a week.

The young desperados were brought before the magistrates again on 12 December to hear their fate. This time all three lads pleaded guilty. In his stepson’s defence John Garner said that:

…until recently there was not a better lad in Batley than his own, and he couldn’t understand what had led the boy astray.11

Being the eldest, James was regarded as the ringleader of the gang and was ordered to receive 10 strokes of the birch.

But James still did not learn his lesson. He appeared in the West Riding Court, Dewsbury, on 16 March 1903, under the name Bowles. Once more John Armstead was alongside him, and yet another boy to come under their influence – 10-year-old Walter Thompson. This time the charge was breaking into the Batley Co-operative Stores at Grange Road, Soothill on 10 March. In fact they made two attempts to gain entry that evening. Initially they used a ladder and smashed a window, but were disturbed. They returned later that night and between 11pm and midnight they broke the plate glass window in the front door, and made off with some boiled ham and oranges valued at 5s. 7d.

Initially James was caught and the other two lads escaped. On finally being apprehended John said “I did not take anything.” Walter denied going in – it seems he was the look-out. And James’ defence was “I did not take the ham, I left it on the counter.”12 Once in court they pleaded guilty.

But James and John also faced a second charge. Two labourers working in Grange Road left their overcoats on a fence at the roadside. The lads made off with them. Charged with this, James said “Armstead took the coats, and found a tin bottle in the pocket, and threw it into a field. He gave me one of the coats.” John admitted “I took the coats off the rails and gave one to Bowles. The one I had was too big, and we changed them, and took them into an office in Grange Road.”13

By this stage the police and magistrates had lost all patience with James and John, with the police saying they had “bad minds”. Whilst young Walter was let off with six strokes of the birch, James and John were sent to the Catholic Reformatory for five years.

That was not the end of it. In early April John Garner appeared before Batley Borough Court where he was ordered to pay 1s. a week towards James’ maintenance in the reformatory school.

The reformatory school has details about James. Inside, his pal appears not to have been his Batley partner-in-crime John Armstead, but a Liverpool-born orphan John Murray. James worked on the farm whilst there and his education was described as very fair, with him able to read, write and do arithmetic (the archaic term of cipher was used in the records).

There is also a physical description. With fair hair and brown eyes, he had a fresh complexion, was of slim build and stood at 3 feet 9 inches tall. He had a permanent burn mark on his right cheek and a scar on the right side of his head.14

There is also a photograph in his records. Uniformed (in the pre-Rev Ottway uniform, so clearly taken in the early period of his incarceration) and seated on a stool, it shows a slim, solemn, unsmiling boy with sloping shoulders and close cropped hair. Unfortunately, because of archives copyright restrictions, I cannot reproduce this photo here – and it is the only one I have of James.

He was discharged early on licence to his parents in Batley on 18 December 1907. By now his character was very good. The school followed his progress annually for three years afterwards. The entry for 12 November 1908 states he worked as a miner and his conduct was ‘S’ – presumably indicating satisfactory. On 6 October 1909 he worked as a general labourer and with ‘FS’ conduct – presumably fairly satisfactory. Perhaps his mother’s death that February contributed to this behaviour dip. The final entry is for 15 October 1910. Returning to mining, his conduct was once again ‘S’.15

The 1911 Census records him working as a hewer in a coal mine and living in the two-roomed house at 5 Spa Street, with step-father John and sisters Mary, Kate and Agnes.16 Other sources state he worked as a hurrier at Soothill Wood Colliery prior to enlisting.17

For many ex-Reformatory lads, the Army was the next step after discharge. However, for James this came later. Although his service papers have not survived, his number indicates he enlisted with the KOYLI in December 1911.

At the outbreak of war he was serving with the 1st KOYLI in Singapore. The Battalion left there for England on 29 September 1914, to form the 28th Division which assembled at Winchester on 23 December 1914. The Battalion was a unit of the 83rd Brigade. James was with them when they embarked for France on 15 January 1915, seeing service in the Ypres salient until the beginning of March. The 83rd Brigade then moved to the Wulvergham area of Belgium, returning to the Ypres salient early in April. The Battalion was present throughout the 2nd Battle of Ypres.

Unfortunately, because his papers have not survived, it is difficult to sketch out his military career. What is clear though is he at some point transferred from the 1st to the 10th KOYLI. In many cases these transfers occurred after a wounded soldier recovered and returned to action.

A newspaper piece in April 1917 stated James was wounded in action about 18 months earlier, so around October 1915.18 From the end of September through to 23 October the 1st KOYLI were in the Loos area, so it is possible it was here James suffered his injury, during the Battle of Loos. This engagement ended on 8 October. The Battalion suffered particularly heavy casualties on 4 October 1915 when at 4.45am they commenced an attempt to recover lost portions of the Hohenzollern redoubt and were met with heavy machine gun and rifle fire from an enemy fully prepared for the counter-attack. In that incident 65 other ranks from the Battalion were wounded.19 But it is not clear if James was amongst these, and there are casualties on other days.

However, whatever the exact timing and location, the 1917 piece goes onto say James completely recovered and rejoined his unit. Perhaps it was at this point after recovery that he transferred to the 10th KOYLI, because towards the end of October 1915 the 1st KOYLI set off for Marseilles as the first stage of their move to Salonica.

It was whilst serving with the 10th KOYLI that James died.

In James’ last letter home he said he was all right, having come through an engagement safely. This final communication was prior to the Battle of the Somme. After this letter his family received nothing more from him. By mid-August 1916 10 weeks had passed since his last letter. And it was now that his family were officially notified he was missing, not having been heard of since 1 July 1916, the opening day of the Battle of the Somme

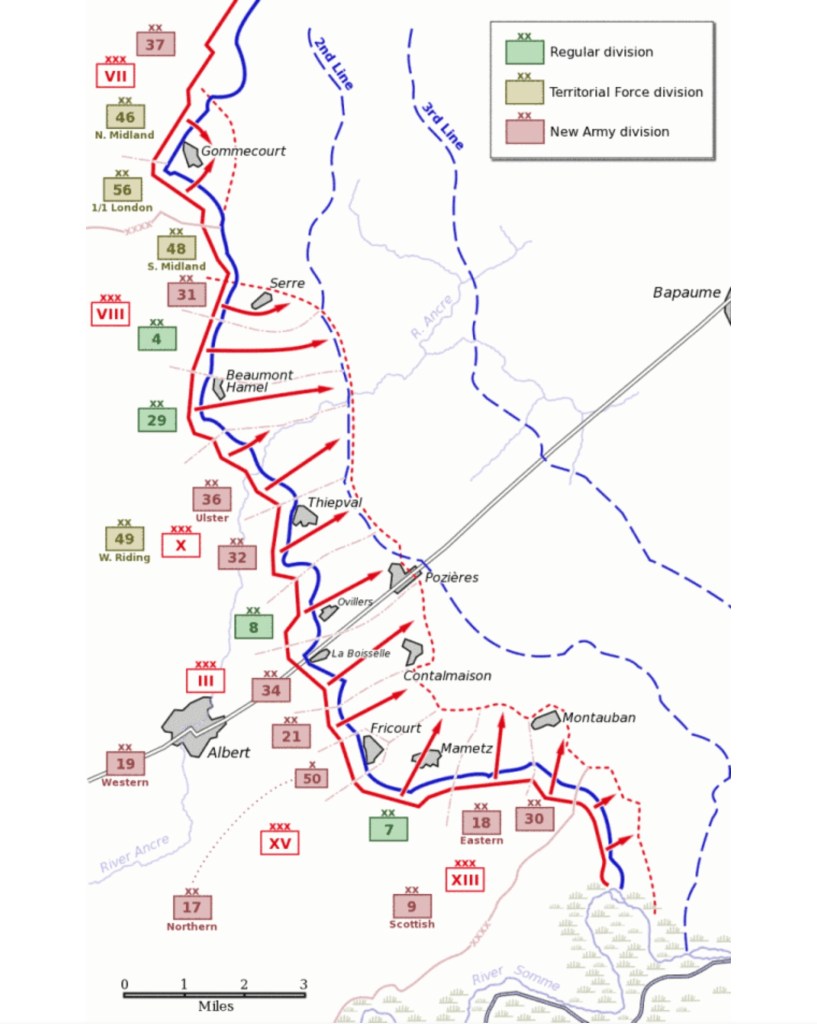

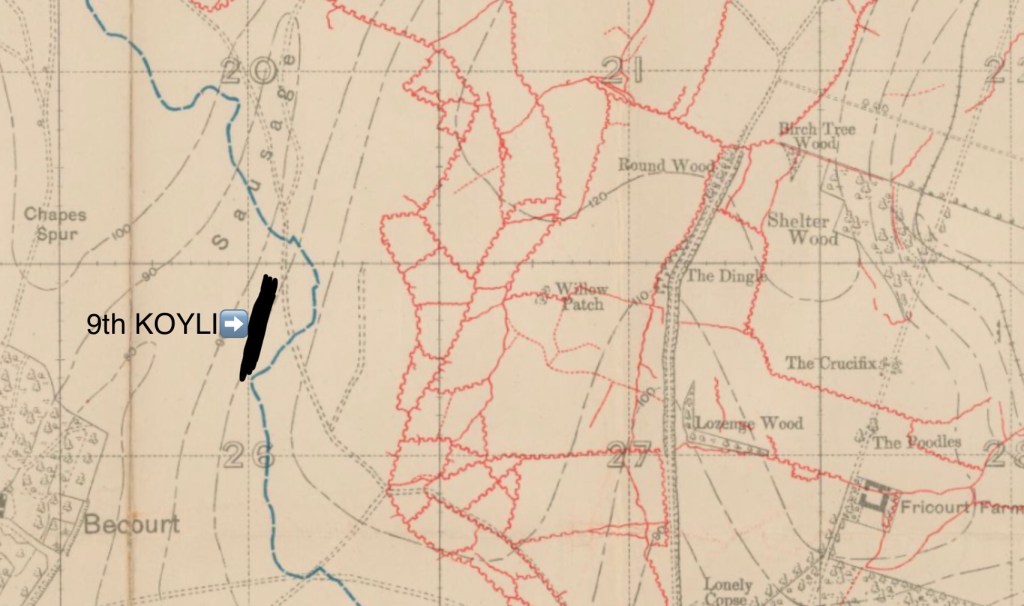

The day James Garner was last seen, the 10th KOYLI, as part of the 21st Division’s 64 Infantry Brigade, were involved in the attack towards the north of Fricourt. The 10th KOYLI led the 64th Brigade assault. It is believed James went into action with another parishioner James Trainor, also with the 10th KOYLI, and also a Spa Street resident. James Trainor died of wounds on 3 July 1916, and his biography is here.

9th KOYLI were part of the 21s Division. British and French front line shown in red, German front line shown in blue. German second and third lines shown as dashed blue lines. British and French objectives on the first day are shown as a dashed red line.

British divisions are colour-coded: green for regular divisions, yellow for Territorial divisions and red for New Army divisions though in most cases the regular and New Army divisions contain a mixture of battalions.

Based on Map 5 from “The First Day of the Somme” by Martin Middlebrook, 1971. – Wikimedia Commons

The Unit War Diary of the day simply reports that they left the trenches at 7.30am, took Crucifix Trench that morning and held it until early the next when they were relieved by the 1st Lincolns.20 The casualty figures in the margin of the diary for the day give more of a clue to the horrors of the engagement – nine officers killed and 16 wounded; 50 other ranks killed, 292 wounded and 135 missing.21

In April 1917 John Garner finally received official confirmation that his stepson had been killed in action on 1 July 1916.

Although James has no known grave, his body was at one point located. On 12 December 1917 a Burial Officer from 5th Corps reported James’ burial. His grave was subsequently lost in the ebb and flow of war, and he is therefore commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing.

James was awarded the 1914-15 Star, Victory Medal and British War Medal. In addition to St Mary’s, he is also remembered on Batley War Memorial.

Footnotes:

1. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 20 March 1903.

2. James Bowles – Records of St William’s Community Home, Market Weighton, East Riding Archives Ref DDSW/12 Page 2638.

3. Bowles was another variant used.

4. The records of St William’s Community Home, Market Weighton (East Riding Archives Ref DDSW/12 Page 2638), give his date of birth as 3 November 1889, but this post-dates his St Mary’s October baptism date. However, in the absence of obtaining his birth certificate, I am inclined to believe the baptism register 13 October date, with corroborating evidence coming from his first Batley Court appearance which was on his 13th birthday.

5. There is some discrepancy in the newspaper around date of death. The Batley News Death Notices of 7 December 1901 said she died on 3 December, which was a Tuesday. The report in the same newspaper said she died at 8’ o’clock on Monday morning – which would be 2 December. I have not obtained her death certificate to confirm.

6. Hicks in his book about The Yorkshire Catholic Reformatory states 700 acres of farmland were given up in 1898, reducing the farm to around 250 acres.

7. Beverley Independent, 28 July 1906

8. Hicks, John D. The Yorkshire Catholic Reformatory, Market Weighton. East Yorkshire Local History Society, 1996.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Batley News, 13 December 1902.

12. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 20 March 1903.

13. Ibid.

14. James Bowles – Records of St William’s Community Home, Market Weighton, Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. 1911 Census, The National Archives (TNA), Ref RG14/27246/40.

17. Batley News, 19 August 1916.

18. Batley Reporter and Guardian, 20 April 1917.

19. 1st KOYLI Unit War Diary, TNA, Ref WO95/2274/1.

20. 10th KOYLI Unit War Diary, TNA, Ref WO 95/2162/2.

21. Ibid.

Other Sources (not directly referenced):

• 1881 to 1901 England and Wales Censuses.

• Batley Cemetery Register.

• Bond, Reginald C. History of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry in the Great War, 1914-1918. London: P. Lund, Humphries, 1929.

• British Army Service Records.

• Clayton, Derek. From Pontefract to Picardy: the 9th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry in the First World War. Tempus, 2004;

• Commonwealth War Graves Commission website.

• GRO Birth, Marriage and Death Indexes.

• The Long, Long Trail website.

• Medal Index Card.

• Medal Award Rolls.

• National Library of Scotland maps.

• Newspapers – various editions of the Batley News and Batley Reporter and Guardian.

• Parish Registers.

• Pension Index Cards and Ledgers.

• Soldiers Died in the Great War.

• Soldiers’ Effects Registers.