At the beginning of February 1947 a wedding took place in Dewsbury Registry Office, between divorcees Otto and Margarete Kornitzer. Those present included their 15-year-old daughter. The Kornitzers – who were living in the home of Hubert Alex Rooke at Field Lane, Batley – were remarrying almost two decades after their first wedding, and five years after their divorce.

This though was only a small part of their story, a story which was part of a much bigger picture. It is a story of a couple caught up in a sickening period of history. It is a story worth re-telling.

Margarete Gertrude Guggenberger was born and baptised on 12 November 1905 at the Alservorstadtkrankenhaus in Vienna. It was a hospital known for illegitimate births, and Margarete’s birth and baptism register entry confirms this in her case. It also confirms her Catholic religion. However, in addition to naming her mother, 23-year-old Amalia Anna Maria Rezincek, the entry crucially also names her father as Karl Guggenberger, a 28-year-old Catholic locksmith. Margarete took his surname.

The couple married the following October in Vienna’s Catholic Church of St Brigitta. Their other children included Pauline Josefine (1907), Karl Paul (born 1908, died 1911), and Richard Karl (1914). They were all baptised in the parish where their parents married. Four years after the birth of Richard Karl, on 26 March 1918 Karl Guggenberger died from tuberculosis, leaving Amalia a widow. She remained a widow for the rest of her life, her death being recorded on 30 May 1930.

Otto Kornitzer’s parents – watchmaker Moritz Kornitzer and Karoline Pessel – married on 6 January 1895 in the Leopoldstadt district of Vienna, an area where many Viennese Jews lived. Otto was born in the city on 24 March 1906. Otto had an older brother, Hugo Pessel, born in 1893, prior to Karoline and Moritz’s marriage; Otto’s older sisters were Margarete (born in November 1895), and Friederike (born in November 1898). All were officially recorded as Jewish.

It is a chilling thought that a little over three decades after Otto and Margarete’s births, entries in Austrian registers such as these could really be a matter of life or death. They would be poured over by the authorities hunting out those with any trace of Jewish ancestry. Margarete’s entries – including her father’s details – would confirm she had none. However, her husband’s Jewish background was beyond doubt.

Although of different faith communities, Otto and Margarete married in Vienna on 9 July 1927. Their daughter was born in 1931. During this period Otto worked as a photographer in a drawing office, a skilled job. Despite growing Nazi propaganda and influence in the country, all went well for the family until 1938.

In that year Austria’s Jewish community was estimated to number around 192,000, a figure which represented almost 4 percent of the country’s total population. The overwhelming majority of Austrian Jews – 170,000 – lived in Vienna, forming 9 percent of the city’s population. From that year all their lives would dramatically change.

For on 12 March 1938 German troops entered the country, met with an enthusiastic welcome by many. The following day Austria was incorporated into Germany. The German annexation of Austria – known as the Anschluss – was approved the following month by 99 percent of the Austrian population. It was a vote which significantly excluded Jews and Roma people. This was a sign of things to come.

The implementation of anti-Jewish measures followed, essentially removing them from economic, cultural and social life. By the summer of 1939, hundreds of Jewish-owned factories and thousands of businesses had been closed or confiscated by the government.

But this was only part of it. On the night of 9-10 November 1938 Nazi thugs, and their supporters, unleashed a co-ordinated torrent of violence against Jews across Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland (land annexed to Germany under the Munich Agreement of 30 September 1938, which now lies in the Czech Republic). The systematic ransacking and destruction of Jewish synagogues, other smaller places of worship, and businesses, took place as police and fire departments watched on. Mass arrests of Jews also ensued, with thousands of Austrian Jews sent to Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps. There were even deaths. The violence meted out in Vienna was particularly brutal.

Kristallnacht as it is better known, (the Night of Broken Glass, so-called because of the staggering number of smashed windows), marked a fundamental shift in the persecution of Jews. It now explicitly included physical violence, forced deportation, incarceration, and murder.

Many Austrian Jewish people now saw the writing on the wall. Despite huge challenges, by May 1939 nearly half of country’s Jewish population had emigrated.

The Kornitzer family’s actions were framed against this backdrop. Otto, in particular, was acutely alert, warning his wife “you never what the Germans will do.”

As a precaution he distanced himself from his wife and daughter, moving into lodgings. He only met them in secret, under cover of darkness. With the increasingly restrictive anti-Jewish legislation, he also recognised the danger his daughter now faced. Those of mixed Jewish-Christian background – like his daughter – were under threat too.

Twice Otto attempted escape to Switzerland by train. Without passport or permission, on both occasions he was turned back. Eventually, assisted by a friend, he obtained a permit to leave, and he and his daughter arrived in England in 1939 just before the outbreak of war.

Margarete was left behind in Austria. Because she was not a Jew she was in less immediate danger. Perhaps the family also thought they would have some time yet in which to extricate her from Austria, not foreseeing how quickly the curtain of war would descend.

Back in England, from February 1939 the British government had been allowing Jewish aid organisations to use a derelict former First World War army camp near Sandwich, East Kent, to house male Jewish refugees. By September 1939, and the outbreak of war, 4,000 men had arrived at Kitchener Camp, also known as Richborough transit camp. They came mainly from Germany and Austria. Amongst the refugees housed there was Otto Kornitzer, who assisted in the camp kitchen.

From 3 September 1939, with Britain now officially at war with Nazi Germany, the position of these men subtlety changed. Tribunals were established to consider, whether on grounds of national security nationals of belligerent countries such as Germans and Austrians should be interned or, if not, subject to other restrictions as enemy aliens. These tribunals extended to Jewish refugees like Otto. His case decision, reached on 18 October 1939, exempted him from both internment and restrictions.

Like many of the Kitchener camp Jewish refugees similarly exempted, Otto joined the British Army serving as a Private with the 74th Company of the Pioneer Corps.

Ranked as a combatant unit, the Pioneer Corps tasks included included building anti-aircraft emplacements on the Home Front, working on the Mulberry harbours for D-Day, and serving during the beach assaults in France and Italy. Pioneers also carried stretchers, built airfields, repaired railways, buried the dead, and moved stores and supplies.

Enlisting on 1 January 1940, Otto was described as standing 5’ 6¾” tall, weighing 155lbs, with a medium complexion, brown hair and eyes. He served throughout the war, and this service included two spells in France, initially between 31 January and 25 June 1940 when France surrendered, and then from 3 August 1944 to 4 October 1945 as France was liberated and Germany defeated. He was demobilised to the Army Reserve on 20 December 1945

His daughter spent her war in Dewsbury, attending school at Dewsbury Technical College.

Margarete remained trapped in Vienna. As Germany’s grip tightened, her position as the wife of a Jew became ever more perilous.

At one point the Gestapo detained her for two days, after hearing she had received a letter from her brother-in-law Hugo in Italy, referencing Karl Marx. They suspected her of conspiracy against the Reich. Fortunately, she was released.

Hugo subsequently made his way to France, from where Otto tried to engineer his escape to England. It was unsuccessful. Hugo was detained in Drancy Camp, Paris, which in the summer of 1942 became the main holding and transit camp for the deportation of Jews from France. In August 1942 he was sent to Auschwitz Extermination Camp in Poland, where he was murdered. It may be that Margarete was oblivious of Hugo’s whereabouts that summer, but she would have been acutely aware of events in her home city of Vienna.

It was from here that in June 1942 her sister-in-law Friederike was deported to the Sobibor Extermination Camp in Poland, where she was murdered. Two months after Friedericke’s removal from Vienna, Margarete’s widowed mother-in-law Karoline was deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto in Czechoslovakia.1 From there she was sent to the Treblinka Extermination Camp in Poland where she too was murdered.

By October 1942 only about 8,000 Jews remained on Austrian soil. The ongoing mass deportation of Jews from Vienna explains why in 1942, to try save herself from persecution, Margarete divorced Otto on grounds of desertion. It worked. She survived the war.

At the end of the war, and once returned to civilian life, Otto was reunited with his daughter. They settled in Batley, living at Field Lane. He eventually found employment with the Cleckheaton firm British Belting and Asbestos Limited.2 The firm were described in advertising as:

Spinners, weavers and manufacturers of Asbestos yarns, cloths, tapes, packings and jointings; manufacturers of Machinery Belting for all industrial purposes; manufacturers of “Mintex” Brake and Clutch Linings and other friction materials.3

Their customers included the motor and aviation industries, and during the war Spitfire, Hurricane and Typhoon aircraft used materials manufactured by the firm.

The Kornitzers made England their home. Otto became a naturalised British citizen in December 1946, with his daughter also being naturalised. And, as 1946 drew to a close, Otto was finally able to get Margarete to England. In this he was assisted by the Vienna branch of the emigration department of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), with whom she had registered in June 1946, giving the UK as her desired destination.4

She had not seen her husband and daughter for around seven years. In fact, her teenage daughter now spoke only English, so Otto acted as an interpreter for them.

Otto also found out that British law recognised their 1942 Austrian divorce, so he and Margarete would have to formally marry again, hence their Dewsbury Register Office wedding at the beginning of February 1947. The press described it as a happy ending for the persecuted Austrian couple.

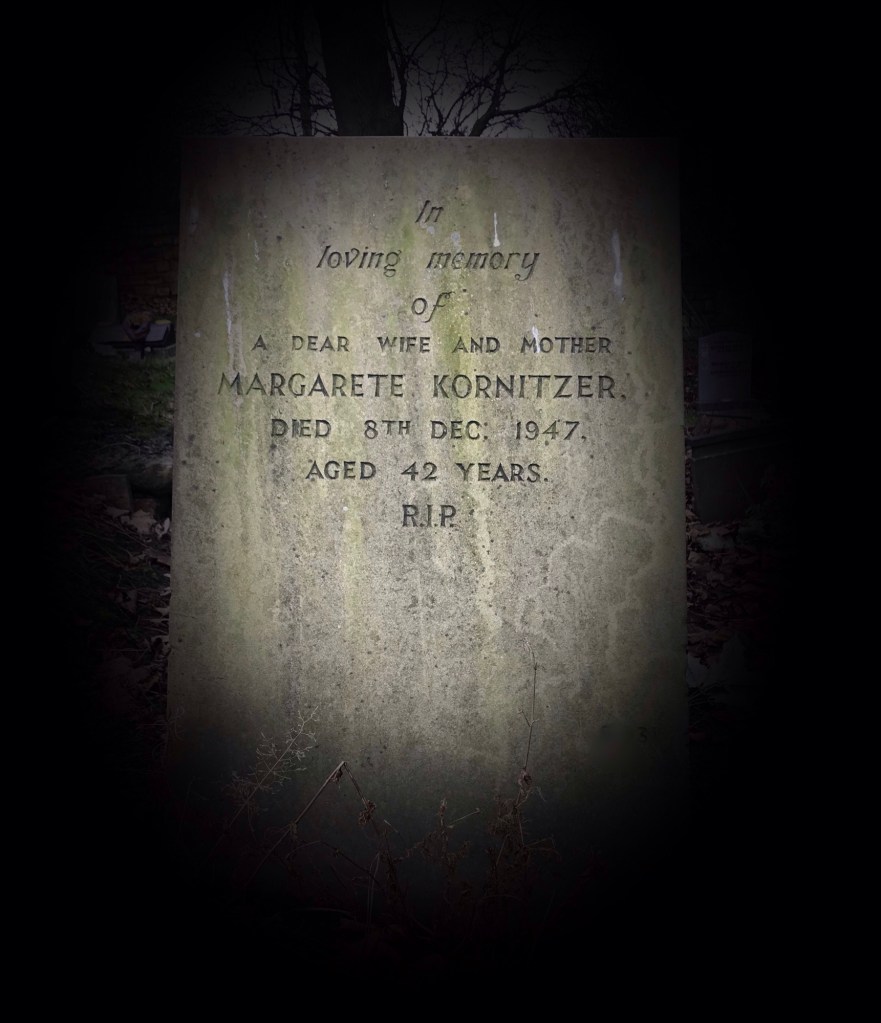

But their happiness was short-lived. On 8 December 1947, less than a year after reaching the safety of England and reuniting with her family, Margarete died in Staincliffe hospital.

Because she remained a Catholic throughout her life, her Batley cemetery burial service was held under the rites of that faith. However, although Field Lane fell within the St Mary’s parish boundaries, it was St Joseph’s Batley Carr priest Fr. James Cox who performed the burial. Nevertheless, because of Margarete’s St Mary’s parish abode and her Batley cemetery burial location, I have included this piece as part of the St Mary’s one-place study.

Otto Kornitzer remarried, and the family subsequently left Batley.

Footnotes:

1. Moritz Kornitzer died in August 1926.

2. According to his naturalisation announcement in The London Gazette, Issue 37887, Page 871, 21 February 1947, he was a wood cutter. – https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/37887/page/871

3. Taken from a British Belting and Asbestos Limited advert from August 1944.

4. Her American Jewish JDC Emigration Service index card incorrectly gives her birth date as 12 November 1895.

Other Selected Sources:

• 1939 Register.

• Austrian Catholic Registers, Baptisms, Marriages and Burials.

• British Belting and Asbestos, Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History, https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/British_Belting_and_Asbestos

• GRO Birth, Marriage and Death Indexes (England and Wales).

• Holocaust Encyclopaedia, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/en

• General Register Office Indexes.

• Kitchener Camp – Refugees to Britain in 1939, https://kitchenercamp.co.uk/

• Munich, Vienna and Barcelona Jewish Displaced Persons and Refugee Cards.

• National Probate Calendar.

• Naturalisation Certificate, TNA Ref: HO 334/229/1854

• Newspapers – various.

• Österreich, Niederösterreich, Wien, Matriken der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinde – Various Records.

• Royal Pioneer Corps, National Army Museum – https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/royal-pioneer-corps

• Service Records – The National Archives.

• Wiener Adressbuch, Lehman’s Wohnungsanzeiger, 1940.

• The Wiener Holocaust Library.

• WW2 Internees (Aliens) Index Cards.

• WW2 Medal Cards

• Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims, https://www.yadvashem.org/archive/hall-of-names/database.html

Postscript:

I may not be able to thank you personally because of your PayPal contact detail confidentiality, but I do want to say how much I appreciate the donations already received to keep this website going. They really and truly do help. Thank you.

The website has always been free to use, and I want to continue this policy in the future. However, it does cost me money to operate – from undertaking the research (various genealogy subscriptions, archive visit costs, document purchases, and ring fencing time away from paid research etc.,) to annual website hosting costs which increase as the information uploaded – and space required for it – grows.

In the current difficult economic climate I do have to regularly consider if I can afford to carry on with my research whilst continuing running the website as a free resource.

If you have enjoyed reading the various pieces, and would like to make a donation towards keeping the website up and running in its current open access format, it would be very much appreciated.

Please click 👉🏻here👈🏻 to be taken to the PayPal donation link. By making a donation you will be helping to keep the website online and freely available for all.

Thank you.